Written in early February 2012 for “En Movimiento.” my bimonthly column for Caiman Cuadernos de Cine. — J.R.

The unexpectedly huge acclaim accorded to Asghar Farhadi’s A Separation in the U.S, appears to be motivated by something more than an appreciation for a better-than-average feature. Is this a sufficient reason for it to be the most successful Iranian film to be released in America to date? Why was it named the best foreign language film of 2011 by the Golden Globes, the National Board of Review, and the New York Critics Circle, and the best picture of the year by the most popular American film critic (Roger Ebert), meanwhile placing third as the best picture by the National Society of Film Critics (which rarely considers films for this category in any language but English, and included only one other such film in its latest top ten, Ruiz’s Mistérios de Lisboa)? Why was it nominated for two separate Academy Awards?

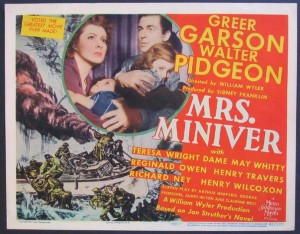

I suspect that an important reason for this sort of enthusiasm is the desire of many Americans — or at least Americans who see foreign-language films — not to go to war again, shortly after the (very) belated return of American troops from Iraq, and during the incessant and frightening beating of war drums by all of the Republican candidates for President except for Ron Paul (who still isn’t taken seriously by the mainstream media–and not because of his radical economic positions, but, to all appearances, because he refuses to support another American invasion in the Middle East). It’s a good example, in any case, of the way that the cultural impact of some films can’t be gleaned from reading reviews and might even be inexplicable to people years later. Who cares today about Mrs. Miniver, the William Wyler propaganda feature of 1942 that won six Oscars, including best picture, director, screenplay, cinematography, actress, and supporting actress, and was nominated for six others?

A Separation also throws into relief a major theme of Iranian cinema that is rarely acknowledged as such, at least outside of Iran — namely, class difference. I can’t speak with any authority about Farhadi’s work because I haven’t seen any of his four previous features, but it does seem evident to me that even though the Persian title of his latest film translates as “[the] separation of Nader [the husband] from Simi [his wife],” which is the major focus of all the reviews of the film I’ve read, the true separation and conflict that produces and sustains most of the film’s drama is between the classes of the two families involved, comfortable middle-class (in the case of both Nader and Simi) and struggling working-class. And if one considers most of the major classics of Iranian cinema, starting with Farrokhzad’s The House is Black and Golestan’s Brick and Mirror in the 60s and continuing through the features of Makhmalbaf and his family, Kiarostami, and Panahi over the next four decades, the huge gap between the rich and the poor — which has lately become a big issue in American politics, for the first time since the Depression, but has been central to Persian culture since its inception — is clearly an inextricable part of their subject matter.

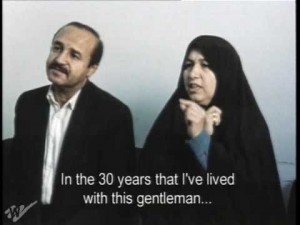

There are also significant differences between the way gender issues are perceived in Iran and in the West. My Iranian-American friend and sometime writing collaborator, Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa, who has seen (and mainly prefers) Farhadi’s earlier features, points out that the huge obstacles Iranian women face in getting divorces — the subject of an excellent 1998 documentary, Divorce Iranian Style (Kim Longinotto & Ziba Mir-Hosseini) — are essentially ignored in A Separation, thus challenging the film’s claims to treat the positions of Nader and Simi with equal amounts of sympathy. In short, what audiences don’t know can be as pivotal in determining the meaning of certain films as what they do know.