This appeared in the April 8, 1988 issue of the Chicago Reader and is reprinted in my first collection, Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism. — J.R.

KING LEAR

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Jean-Luc Godard

With Peter Sellars, Burgess Meredith, Jean-Luc Godard, Molly Ringwald, Norman Mailer, Kate Miller, Leos Carax, and Woody Allen.

Jean-Luc Godard’s latest monkey wrench aimed at the Cinematic Apparatus — that multifaceted, impregnable institution that regulates the production, distribution, exhibition, promotion, consumption, and discussion of movies — goes a lot further than most of its predecessors in creatively obfuscating most of the issues it raises. Admittedly, Hail Mary caused quite a ruckus on its own, but mainly among people who never saw the film. King Lear, which I calculate to be Godard’s 34th feature to date, has the peculiar effect of making everyone connected with it in any shape or form — director, actors, producers, distributors, exhibitors, spectators, critics — look, and presumably feel, rather silly. For better and for worse, it puts us all on the spot; as Roland Barthes once wrote of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Saló, it prevents us from redeeming ourselves.

From its birth, a table-napkin contract signed by Godard and producer Menahem Golan of Cannon Films at the Cannes Film Festival in 1985, to its disastrous world premiere at Cannes two years later, the project has always seemed farfetched and unreal, even as a hypothesis. Read more

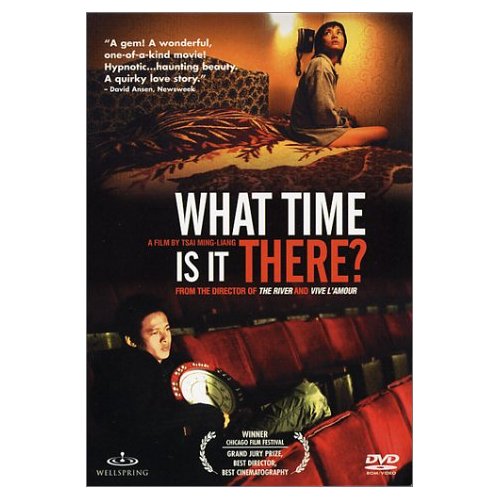

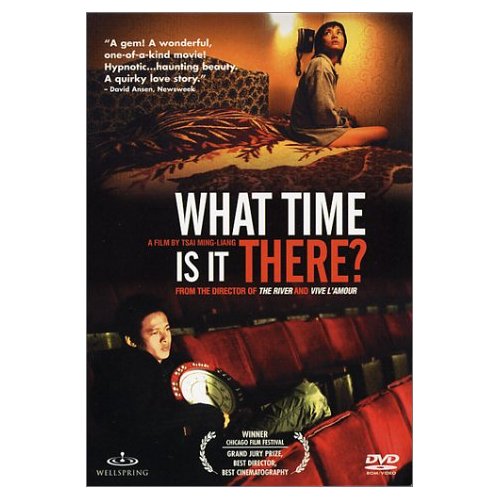

From the March 1, 2002 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

What Time Is It There?

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Tsai Ming-liang

Written by Tsai and Yang Pi-ying

With Lee Kang-sheng, Chen Shiang-chyi, Lu Yi-ching, Miao Tien, Cecilia Yip, and Jean-Pierre Léaud.

After hearing the adagio of a Schubert chamber work: there is nothing more beautiful than the happy moments of unhappy men. This might serve as a definition of art. — The Diaries of Kenneth Tynan

Toward the beginning of his essay “The Crack-Up,” F. Scott Fitzgerald notes that “the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.” That might well describe the agenda of a poetic and philosophical Taiwanese-French feature, Tsai Ming-liang’s glorious two-part invention What Time Is It There?, which premiered at Cannes last year and is opening at the Music Box this week (assuming the theater reopens after some trouble with health inspectors). It feels more contemporary, at least from a global perspective, than any other new movie in town, and central to it is an examination of separateness and togetherness, unity and disparity in two separate countries in two separate parts of the world. Read more

The following was commissioned for and included in the 17th edition of the Time Out Film Guide, (2008), and is being reprinted with the publisher’s permission. Thanks also to John Pym, the book’s editor, who proposed that I write this piece so that it would come out before the Presidential election. –J.R.

BUSHWHACKED CINEMA

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

When the history of American movies during the eight-year reign of George W. Bush (2001-2009) eventually comes to be written, one might hypothesize that the commercial development of the mobile phone during the 1980s and 1990s and the introduction of the iPod during the first year Bush took office were crucial in setting the stage for some of the basic conditions of that era. Arguably for the first time, one could easily sustain one’s ignorance about and indifference to one’s fellow citizens even while sharing the same public space with them–on the street or in other public locations dedicated to some form of transport: terminals, buses, subways, trains, planes, fairgrounds, theme parks, and, above all, cinemas.

So the phenomenon of a U.S. President who, to all appearances, preferred to remain blissfully (and strategically) ignorant about the news and the overall state of the world, and ran his office accordingly, was part and parcel of this growing trend to eliminate the public sphere from American life and subdivide the entire culture and society into `special interest’ groups and niche markets. Read more