From The Soho News (October 29, 1980). — J.R.

What attracted me to sign up in advance for a symposium called “Television/Society/Art,” put on at the Kitchen and NYU last weekend, was the opportunity to see and hear some old friends, encounter some new people, and maybe even get some new ideas (about what I should be reading and seeing, if nothing else): a bargain for the $10 registration fee.

Presented by the Kitchen and the American Film Institute and organized by Ron Clark, a senior instructor at the Whitney Museum’s Independent Study Program, the three-day event inevitably threatened a few dead spots — particularly to a virtual videophobe like me, who largely regards the medium as a kind of wicker basket holding a few magazines that I’m neither interested in reading nor quite ready to throw away. On the other hand, the fact that some of the invited panelists seemed to share the same bias made me suspect that I’d feel right at home.

The symposium got off to a somewhat inauspicious start with the presentation of a lumbering keynote paper entitled “Television Images, Codes and Messages” by Douglas Kellner, a teacher of philosophy at the University of Texas’s Austin campus. This is one of those all-enveloping academic machines designed to engorge and magically synthesize every fashionable theory in the firmament, including several in frank contradiction with one another, into one all-purpose shining beacon — designed, like TV, to lull us into passive acceptance of anything and everything.

Rather gracelessly written (e.g., “Low-key classical music introduces the higher-brow world of public television”), Kellner’s paper nevertheless brought the symposium to life through the healthy opposition that it inspired. English theorist Stephen Heath responded first by wondering whether one should uncritically assume that TV “communicates” when it is in fact TV itself that produces this notion — a point that became amplified by French writer Berenice Reynaud, who suggested that it was more interesting to look at TV as if it were communicating nothing.

Kellner more or less agreed, arguing for a pluralistic use of critical methodologies; art critic Rosalind Kraus promptly accused him of intellectual dishonesty — creating the illusion of collective endeavor in the same way that TV does, by co-opting everything that everyone was saying. (I have to admit that Dick Cavett crossed my mind more than once.)

***

There’s an apocryphal story about Will Rogers that topical humor entered his stage act after he once started reading aloud from a newspaper at random and discovered that his audience laughed uproariously at every line. Whatever the reasons, a significant number of the best contributions to the symposium were quoted texts and commentaries on those quotes.

Julianne Burton, a contributor to Jump Cut, and October editor Annette Michelson both quoted and discussed magazine ads. Burton analyzed the ideology of certain ads for TV sets, which she projected as slides. Michelson read aloud from a spread selling 300 frames-per-second Polaroid Analyzers, as a prelude to discussing the widespread uses of video surveillance systems.

Allan Sekula — a smart, angry photography critic who takes a hardline radical position about independent video (“We can no longer speak about an autonomous high culture”) — quoted and contrasted course descriptions in two college catalogues. L.A. City College, an inner-city school largely serving a “third-world student body,” in a catalogue resembling “TV Guide without ads,” offers a broadcasting course built around a mythical cult of “personality” and the individual announcer. The “very expensive” San Francisco Art Institute, in a catalogue that looks like Artforum and features theoretical articles, offers free verse “in an anarcho-nihilist manner” to describe a video/performance course.

Herbert I. Schiller, author of The Mind Managers and a very charismatic, crusty debunker, brightened both the Friday sessions with wonderfully sarcastic readings of items from the New York Times business section. (One was about a futuristic, bookless library planned for Clarkson College.)

Schiller also offered some terse asides about the ways in which we usually discuss TV. This included abuse of the term “free flow of information” in international terms (when it means free only to those with receptors and those who are able to benefit from the media monopolies). He also objected to the anthropomorphism that TV is subjected to, such as the habit of saying that it’s still a “young” medium. (“TV never had a youth. It started out decrepit.”)

***

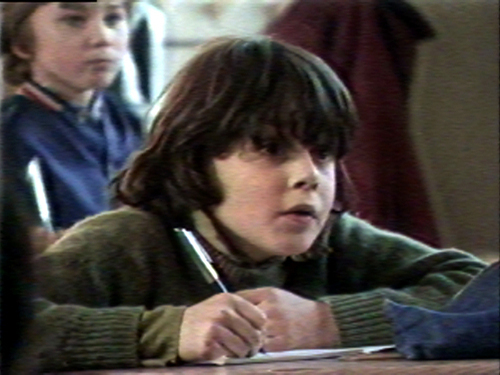

For me, however, the most important single “quotation” at the symposium was the screening in color of two half-hour episodes from Godard’s brilliant France Tour Detour Deux Enfants series for French TV, financed by a state-run channel and then shown there only reluctantly. Translated and contextualized by Elizabeth Lebovici and Berenice Reynaud, ho helped show how much of this exciting work is a commentary on the rest of French television, these two shows were selected by Godard himself (in absentia) out of a series of 12.

One hopes that it won’t be long before we can see the entire series, for the two samples shown make Godard’s Every Man for Himself look like child’s play. In each emission, Godard interviews a child, addressing a little girl, Camille, about sound and music and a little boy, Arnaud, about image. Deliberately placing himself in a dialectical relationship to an uncontrollable outside world, Godard succeeds splendidly here in overcoming the abstract solipsism that often dogs his work, whether offering an account of a contemporary bookstore, focusing in beautiful closeup on a radio dial, or trying his pithy wisdom (about the relation of TV screens to shop windows) out on a skeptical 9-year-old.

Among many dramatic splits at the conference was one between video theorists and video makers, exacerbated by the lack of any work shown other than Godard’s, and the relative sparsity of video artists on the panels. At the final session, Kitchen director Mary McArthur gracefully acknowledged this problem and ended with an expression of the desire to show more video work at the Kitchen.

Certainly a big rift came from the tension between panelists who essentially questioned (or dismissed) TV or video as a viable possibility and many others present, including several nonpanelists, who devoted their careers to using the medium. But equally striking was the issue of how women were (and weren’t) included in the original symposium program — amply represented on panels devoted to “Television and Art” and “Television and Cinema,” but (perhaps significantly) absent from the Sunday panels on “Ideology in Television” and “Television as Politics”.

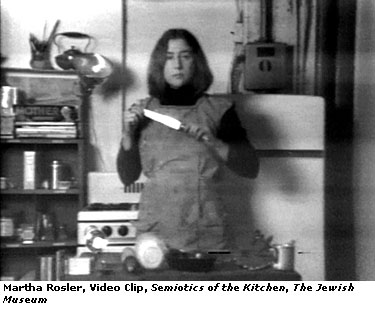

In quick response, Ron Clark conceded his error and promptly invited feminist critic Sandy Flitterman and video artists Martha Rosler and Kim Fitzgerald to participate, aided in part by the gracious offer of Kellner to drop out of the final session. (As “Media Ecology” graduate student Arlene Krebs pointed out, all the panels were uncomfortably overloaded.)

Flitterman, who stated that “representation and desire are not separate entities, but in fact occasion each other,” later argued that the characterization of the image as irrational, illogical, and fragmented by certain male Marxist critics on her panel made verbal language much more privileged. In her attack on male ideology, she was persuasively seconded by film teacher Pat Mellencamp, who spoke of the frequency of the male announcer’s voice in enunciating feminine desire on TV.

By the end of the exhausting weekend, at a reception for the participants, debates that had run through the mill were temporarily allowed to coast along in their typically unresolved states. It was a party thrown to say neither “please” nor “thank you” to anyone, but rather to allow people of like temperaments and interests to get together and chatter — the point of the entire weekend.