It would obviously be hyperbolic for me to claim that the editorial evisceration originally suffered by this article was comparable to some of the curtailments experienced by Richard Pryor when he appeared on TV or in the Hollywood mainstream, but that’s more or less what it felt like to me at the time. I recently and very belatedly uncovered all but the last paragraph or so of my original version (after posting mainly the published version several months earlier), which I’ve reinstated here [on November 14, 2011]. The fact that the editor who placed this article in a lead section of Film Comment’s July-August 1982 issue entitled “The Coarsening of Movie Comedy” also changed my title to “The Man in the Great Flammable Suit” may give some notion of what his evisceration felt like at the time.

My working assumption in restoring original drafts on this site, or some approximation thereof, isn’t that my editors were always or invariably wrong, or that my editorial decisions today are necessarily superior, but, rather, an attempt to historicize and bear witness to my original intentions. It was a similar impulse that led me to undo some of the editorial changes made in the submitted manuscript of my first book, Moving Places: A Life at the Movies (1980), when I was afforded the opportunity to reconsider them for the book’s second edition 15 years later (now out of print, but available online here) — not to revise or rethink my decisions in relation to my subsequent taste but to bring the book closer to what I originally had in mind in 1980.

Richard Pryor Live in Concert (1979) remains for me a key work; when I curated a month-long program for the Austrian Filmmuseum in October 2009, The Unquiet American: Transgressive Comedies from the U.S., this was the only significant selection of mine that had to be omitted, simply because of the obtuseness of the film’s distributor when it came to sending any print out of the country. I also recall that when Manny Farber, during the q and a session after his legendary lecture at Museum of Modern Art in 1979, was asked what interested him the most in contemporary movies, this was the single item that he cited. –- J.R.

1. R.P. & Charlie C.

I’m sorry, but I don’t want to be an emperor. That’s not my business. I don’t want to rule or conquor anyone. I should like to help everyone – if possible – Jew, Gentile, black man, white….To those who can hear me, I say, do not despair. The hate of men will pass and dictators die and the power they took from the people will return to the people….In the name of democracy, let us unite!

— Jewish barber (Chaplin) in THE GREAT DICTATOR

At the center of Richard Pryor’s comedy is his grasp of poverty and weakness, pain and defeat — the very reverse of that strength and self-confidence which he can project so powerfully on a stage. Within the taut dynamics of his performance art, complex attitudes about success and failure, pride and shame, wealth and poverty, love and self-interest are constantly being formulated in relation to one another — guaranteeing the authenticity of his popular appeal, and the beauty and honesty of his self-scrutiny.

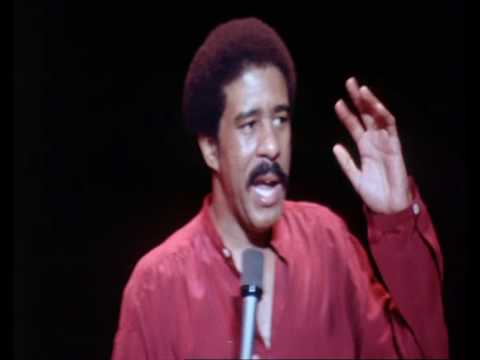

To get some measure of the imaginative empathy that Pryor can invest in his creations, his capacity to examine the reverse side of every coin, one need only compare his deer hunt in RICHARD PRYOR LIVE IN CONCERT (1979) with Michael Cimino’s, in an Oscar-winner released only a few months earlier. For a big-time auteur like Cimino, intent on filling out a grand mythic design, the question of how a frightened deer drinks water never gets posed. R.P. does more than pose it; he becomes a frightened deer drinking water — along with himself as a kid and his father watching — in order to find out.

This has a lot to do with the art of a Chaplin as well. LIMELIGHT, for instance, set in London’s East End around the turn of the century, unfolds around the same time that the father of the film’s star, director, writer, producer, and composer — a music-hall performer and alcoholic, also named Charlie Chaplin — died in abject poverty. Thus Chaplin’s speculative portrait of himself in 1952 as a has-been and failure is possibly based on what he might have become had he remained in English music halls, and clearly reflects the fate of his own father, whom he barely knew.

The way that, even at his most egotistical and self-indulgent, Chaplin was able to construct an auto-critique founded on the antithesis of his fame and fortune, helps to define what makes him a great filmmaker, and Richard Pryor a great performer. Theirs is an art of rigorous dialectics shared with a mass audience, a game that few comics are capable of sustaining. Correspondingly, it is the absence of such dialectics in the work of Woody Allen -– the literal absence of non-whites on the streets of his classy travel-poster MANHATTAN, or marginal working-class types in the Gothic recesses of his STARDUST MEMORIES -– that prevents him from becoming major.

As it happens, Chaplin and Pryor also take in Woody Allen’s key subject, the spectacle of middle-class consumption. Think of Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux, a close cousin of Hannah Arendt’s portrait of Eichmann as model bourgeois; or consider Pryor’s side-splitting rendition of paranoid whites returning after intermission in RICHARD PRYOR LIVE IN CONCERT (“I love this part where the white people come back and see that the niggers have stolen their seats”) –- a routine regarded as reverse racism by such middle-class beacons as Vincent Canby and Andrew Sarris. But Pryor and Chaplin never make the mistake that Allen does, of confusing the part with the whole, or middle-class Manhattan with the universe.

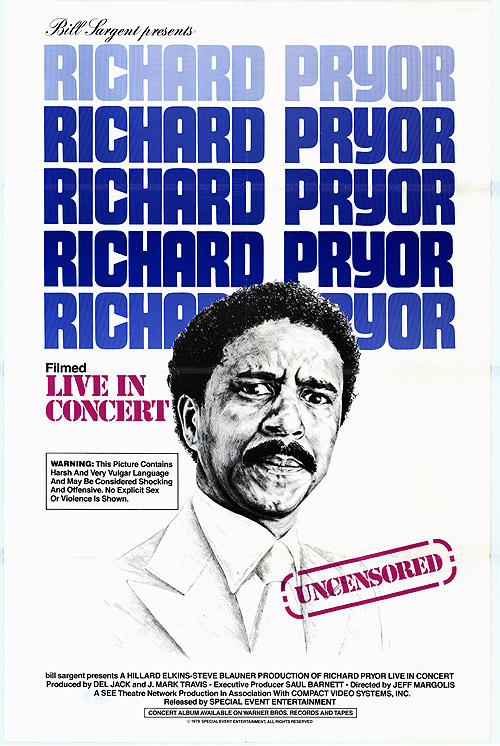

One might argue, in fact, that all three comics can be defined by their separate constituencies, and judged by their individual relationships to them, which amount to political mandates. Woody Allen betrayed his own middle-class mandate in STARDUST MEMORIES by insulting his supporters; at the end of RICHARD PRYOR LIVE ON THE SUNSET STRIP, Pryor thanks his audience for supporting him through his near-brush with death -– “You gave me a lotta love when I wasn’t feeling well” -– and then gently chides them for telling nasty jokes, like the sight gag equating a moving lit match with R.P. in flight.

According to Pauline Kael, the new Pryor concert movie “goes thud” when Pryor, in response to requests from the audience, sits down on a stool and goes into his Mudbone routine, because this section “doesn’t have the crackle of a performer interacting with an audience.” I strongly suspect that Kael would fault Chaplin’s speech at the end of THE GREAT DICTATOR -– that unnerving moment when the Jewish barber changes imperceptibly into Chaplin himself -– on similar grounds, and it’s easy to see why. But it must be acknowledged that these are the parts of both films that matter the most politically,as testaments and acts of witness: Chaplin’s collapse of his own fiction and direct address to the spectator, quoted above; Pryor’s presentation of his own gaudy success seen through the eyes of a poor rural black from Mississippi, uneducated yet skeptical. (“I know that boy, he fucked up….Fried what little brains he had. Don’t let him get any of that powder in his nose; that’s like tryin’ to talk to a baboon’s ass.”) In both cases, the comic finds he has to step outside his customary persona in order to speak the truth. For Pryor, this logically precedes his account of his near-fatal accident from freebasing cocaine.

What is it that makes us squirm through Chaplin’s speech and, to a lesser extent, Pryor’s Mudbone monologue? It’s not so much the comedy as the withdrawal of comedy at strategic junctures of THE GREAT DICTATOR, MONSIEUR VERDOUX, LIMELIGHT and A KING IN NEW YORK that makes us nervous. Pryor, on the other hand, doesn’t so much sidestep comedy as bypass the easy route to belly-laughs that he pursues later, focusing here on the dialectics of self-confrontation. In both cases, a partial retreat of the comic from his audience imposes a certain Brechtian distance.

What are Chaplin and Pryor each doing in these sequences but reminding us who they are, and where they’re from? In at least one respect, the total inadequacy of Chaplin’s speech as a response to Hitler in 1940 — as art, as thought, as action, as anything — becomes the key truth that the film has to offer. Annihilating the tramp before our eyes in order to speak as himself, Chaplin simultaneously resurrects the Tramp existentially, in a much more profound way, through the exposure (however unwitting) of the brutal fact of his own helplessness. He’s revealing, in short, that even the famous Charlie Chaplin can’t save the world, just as Pryor is revealing candidly that on one level, even a powerless nitwit like Mudbone from Tupelo has more smarts than he does when it comes to sheer common sense and self-preservation.

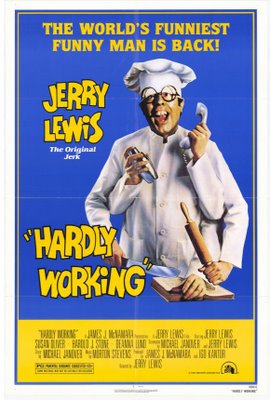

Let’s bring a final self-witness into the act. Leonard Maltin has pointed out that Jerry Lewis, while playing an unemployed circus clown in HARDLY WORKING, still wears his Cartier wristwatch and other expensive jewelry to signal to his audience that he’s hotshot celebrity Jerry Lewis as well as a funnyman out of work — a rather grotesque (or, at the very least, mannerist) dialectic that remains operative throughout Lewis’s last feature (which largely became a hit because of its working-class audience).

Pryor is essentially caught in the same dilemma now, and the interest of his latest work often consists of seeing how he deals, from moment to moment, with this problematical impasse. Living (as Chaplin did) in a country where success can constitute no less deadly a trap than failure, he walks a very narrow tightrope that can snap at any moment, inviting us to watch his progress. Like any jazz musician, he depends vitally on this sexy form of suspense that keeps everyone off-balance.

***

2: R.P. and Charlie P.

I don’t like movies when they don’t have niggers in them. I went to see LOGAN’S RUN, right? They had a movie of the future called LOGAN’S RUN. There ain’t no niggers in it! I said, “Well, white folks ain’t plannin’ for us to be here!” That’s why we gotta make movies….

— Pryor in Bicentennial Nigger (1976)

Unfortunately, unlike Charlie C., Woody A., and Jerry L., Richard P. doesn’t make movies; he gives performances. And apart from his two concert films, where the performance more closely equals the movies, his performances are taken by other people, who make their own movies out of them.

Frankly, I don’t harbor too many extreme hopes for Pryor’s performance as Charlie Parker in a movie currently being planned by Joel Oliansky, any more than I can sustain many memories of his performance in LADY SINGS THE BLUES as Piano Man (an amalgamation of gloss and nervous talent, based on a confused part squeezed out of little pieces of Lester Young scrambled by Hollywood, and served up with tasty sugar-cured ham). Pryor always “does his best” in such circumstances; in SOME KIND OF HERO, he provides us with our only reason for seeing the movie. But even if he seeks out these formats or at least willingly submits to them, he always has to relinquish most of his power as a performer -– the capacity to create a world of his own -– in the process. The results are sometimes as lamentable (if also as tunefully poignant) as Charlie Parker’s celebrated sessions with strings, which has always made me think of a plaintive swan drowning in bubble bath.

I anticipate, in other words, that whatever truths are to be found in Pryor’s performance as Parker (assuming that it ever materializes), they won’t necessarily be congruent with those of Joel Oliansky, or with Ross Russell’s Bird Lives! The High Life and Hard Times of Charlie (Yardbird) Parker -– the best jazz biography that I know, and probably the least suited for absent-minded Hollwood hagiography. (Written by the white producer of Parker’s celebrated Dial sessions in the Forties — which includes everything from the disastrous 1946 west coast “The Gypsy” and “Lover Man,” when C.P. was wasted on phenobarbital, to the sublime 1947 east coast “Embraceable You” and “Bird of Paradise,” when he was sailing on smack — Russell’s book has plenty of high-powered dialectics of its own. At their last meeting, around Christmas 1954, Parker threatened the author/producer with a gun for having released “The Gypsy” and “Lover Man”.)

Despite the resemblance between Pryor’s career and Parker’s in many salient respects –- from humble Midwestern origins to crippling drug dependencies, suicidal behavior, and countless domestic crises (one can even compare Pryor’s intricate employments of obscenity with Parker’s uses of sixteenth notes), I don’t see much possibility of Pryor using Parker — or being allowed to use Parker– as the chord structure for his own free-flowing solos, which are too uncontainable and volatile in Hollywood terms. That Pryor keeps getting roped into these aesthetically doomed enterprises seems a central aspect of his popular role as victim. Like Orson Welles, he seems capable of winding up in anything for fast money, and then doggedly assuming the niche of the frustrated artist -– contributing a Niagara of creativity to the work of mainly untalented plumbers, rather than being entrusted with the responsibility of creating and directing a flood of his own.

The prodigal waste that ensues can be awesome. My cousin Joseph Lelyveld, a New York Times reporter, once described to me watching Pryor tape a TV show with a live audience — delivering a brilliant and obscene tour de force that everyone knew in advance would be completely unusable (apparently less than 90 seconds wound up getting broadcast), yet continuing undeterred with endless quantities of anger, wit, and energy. One could argue, of course, that such behavior is “wasteful” only in business terms. (I’m sure that many members of Pryor’s studio audience, my cousin included, considered their own time well-spent.) There are equivalent stories, of course, about “Bird” playing with hillbilly groups and polka bands, which I suppose is part of the same sort of populist tradition.

Out of the twenty-seven fiction features that Pryor has played in, I’ve seen eleven. Only two of these, for my money, make fruitful and satisfying use of Pryor’s dialectical gifts in any concerted way, by placing him at an oblique angle to the rest of the movie — letting his part and presence constitute a critique of everything else that’s going on. They’re respectively one of his least and one of his best known films, SOME CALL IT LOVING (James B. Harris, 1973) and CAR WASH (Michael Schultz, 1976) — and interestingly enough, each explores the opposite side of Pryor’s public persona, the CITY LIGHTS duality of tramp and wealthy dude.

In the first movie, R.P. logically winds up in a coffin under an R.I.P.; he is such a total loser that there is nowhere else for him to go. His character is Jeff, a derelict dying of drink and drugs, whose life and devotion seemingly revolve around Troy (Zalman King), a white millionaire and dreamy vacuum with a sour expression who plays a mean baritone sax in a slick nightclub. The vision, of course, is a hallucinated one — conjured up by former Kubrick producer James B. Harris, out of John Collier’s wry story, “Sleeping Beauty”. It’s a haunting, bittersweet fable about the fatal temptation of Hollywood dreams and the capacity to buy them — and consequently a movie that many of my more defensive and less disenchanted colleagues tended to dismiss.

Into this solipsistic and absurdist framework commanded by Troy (who purchases a Sleeping Beauty [Tisa Farrow] from a carnival and dutifully waits for her to awake) — which parodies the moviegoer’s own isolation and passivity — staggers the disheveled and battered Jeff. Barely able to speak or walk, he drools on the floor of the men’s room at the nightclub, coughs horribly, stutters and stammers and laughs raucously, finds he can’t piss, scrawls something incomprehensible on the wall with a red Magic Marker (and hoots with manic joy, “Day-Glo!”, after he insistently gets Troy to turn off the lights), and worships Troy’s sax playing without qualification. (Try to imagine a rocket ship carrying Pryor at his grungiest into LAST YEAR AT MARIENBAD, if you want some faint sense of the uncanny incongruity he creates in this sleepwalking ballet.) He also figures as the hero’s best and only friend, whose lack of freedom Troy perversely envies; and when Jeff inevitably kicks off, Troy makes the lush funeral arrangements, for an elaborate ceremony that practically no one attends. Throughout the movie, Jeff’s freaky, unbridled presence is allowed to function as the only directly expressive human element in Harris’s grimly beautiful tapestry –- ironically, the only character who’s not pointedly governed by obsessive rituals.

By contrast, Pryor plays the only wealthy black character in a gem called CAR WASH -– a gracefully stylish populist musical that made certain middle-class critics flinch and blanch at gags involving, shit, piss, and vomit. As if in response to an earlier car-wash disco anthen, “Put Your Money Where Your Mouth Is,” the infamous Daddy Rich arrives on the scene in his endlessly protracted gold limousine (a vivid Tex Avery nightmare, a veritable dachshund of a car) — heralded and greeted, even cheered as he emerges in a sleek white suit, surrounded by a fawning court of singing soul sisters (also black, and dressed in white). Happily spreading the word about the Church of Divine Economic Spirituality, in which “money talks and bullshit walks,” Daddy Rich comes across like a Father Divine in hipper threads who preaches the cause of black capitalism to underpaid car washers.

Clinching the bitter irony of his appearance (a much more lethal weapon in the movie than a would-be black revolutionary called Duane [Bill Duke], who tells Daddy Rich, “You’re talkin’ just like a pimp”), an elderly shoeshine “boy” with white hair begs for the privilege of shining his shoes, amidst general delight from workers and acolytes. “I take what is given unto me,” Rich replies preacher-style, piously framed against portraits of JFK and Martin Luther King. As reported in these pages five summers ago, when I saw this film with a mainly black audience in Philadelphia, the mean satirical thrust of this sequence provoked some spiteful walkouts; I don’t imagine they would have liked Mudbone from Tupelo, either. Yet seen today, there’s a certain way that Daddy Rich anticipates -– and even parodies in advance -– the triumphant R.P. in LIVE ON THE SUNSET STRIP, with his red suit, his Billy Dee Williams strut, and his gab about expensive lawyers.

Both of these memorable fiction performances are based on an economical eyedropper principle –- like Jackie Gleason’s carefully measured presence as Minnesota Fats in THE HUSTLER, or Charlie P.’s inspired single choruses in some of his fleet competitions/collaborations with the Woody Herman band. Given more rope as well as more (or less) slack, Pryor usually bebops his way through other parts with the intermittent resourcefulness (and much of the throwaway off-handedness) of Parker in his prime -– like the uneven virtuoso parts in the next two movies directed by Michael Schultz after CAR WASH, WHICH WAY IS UP? and GREASED LIGHTNING (both 1977), or the rare verbal and kinetic energy he contributes to the opening moments of BLUE COLLAR (1978), before Paul Schrader’s duller dynamics and anti-union platitudes take over.

In the explosive meeting-place between physicality and language (where many of our most optimistic contemporary masterpieces have taken root, from Ulysees to PLAYTIME), Pryor’s body functions as one of the most supple and varied instruments for human expression to have existed since Parker’s chops intersected with a blues. When a puritanical friend and avant-garde filmmaker recently told me that he stayed away from Pryor because he preferred language humor to body humor, I argued that sometimes R.P. made the two categories indistinguishable. (“Language is the house that man lives in,” says the heroine in Godard’s 2 OR 3 THINGS I KNOW ABOUT HER, echoing Tati’s equation in PLAYTIME of architecture and communication.)

Consider R.P.’s astonishing re-enactment of being beaten by his grandmother in LIVE IN CONCERT (“Don’t-you-run-from-me — not as long as you black!“) — one word per stroke, as he sculpts a staccato, crab-like chain of blows given and received across the stage, oppressor and victim maniacally encased inside the same voice and body. Then he discovers that he can’t reply to the verbal charges without having his words repeated precisely by his grandmother, to the tune of further blows. As a musical/physical experience, this is as rich with overlapping rhythms and textures as the switcharound breaks featuring sustained flurries of notes taken by Charlie P. on “A Night in Tunisia” –- and, miraculously enough, just as funny.

***

3. R.P. & Mister Charlie

At a time when race relations in America have degenerated from unspoken resentment to mutually acknowledged hostility, when school integration programs have ground to a near halt, when the Reagan administration is working overtime to undo all that the 1954 Supreme Court decision made possible, when unemployment among blacks is more than twice that of whites, Richard Pryor is a star….A black man stands on a stage and ticks off the foibles of “white folks” and “niggers”. It is as if absolution were being granted…

…The fact that American society is desperately in need of satire at this particular moment partially accounts for the perception of Pryor in such a fashion, but something else is going on. A black man who barks but doesn’t bite is irresistibly appealing to a nation torn apart by racial strife.

— David Ehrenstein, “Beginning of the End of Richard Pryor,” Los Angeles Reader, April 9, 1982

Beginning with this provocative charge by a black critic that Pryor is currently being used -– with or without his own awareness or control -– as a vehicle for political containment, even in his latest concert film, we might as well stress that whatever his comic/dialectical gifts and/or his limitations, Pryor is not about to be reducible to the needs and dictates of anybody’s particular political program. (Neither was Chaplin or Parker, nonjoiners both, although both were hounded and harassed by bluenoses and official law-abiding bodies as if they were -– the first out of America, the second to his death.)

In their recent non-book on Pryor called This Cat’s Got 9 Lives! (Delilah), Fred Robbins and David Ragan recall, among other notorious events, Pryor’s diatribe at a Gay Lib benefit at the Hollywood Bowl in 1977 -– apparently provoked, according to Michael Schultz, by Pryor having observed racist behavior backstage just before he appeared. Lambasting an audience of 17,000, most of them white, for “cruising” on Hollywood Boulevard “when the niggers was burning down Watts,” he reportedly went on for fifteen minutes of abuse before exiting with an invitation to “kiss my happy rich black ass” –- a sassy sign-off that sounds a bit like smooth Daddy Rich and crazy Jeff rolled into one.

The ads for the unrated LIVE IN CONCERT showed us a realistic drawing of R.P.’s face and torso -– pained, piqued and angry, practically crucified in his jacket and tie, but life-size. Three years later, ads for the R-rated LIVE ON THE SUNSET STRIP –- released in a noticeably smaller country shrunk by Reaganomics and the devaluation created by hyperbole — show him considerably larger than life, a Gulliver on the Strip with cheering crowds below, holding one foot and yammering in agony as if a car has just run over it. In this passage from life-size equal to oversized icon, Pryor may indeed be, as Ehrenstein fears, embarked on the beginning of his end. In America, this is called “success”.

LIVE IN CONCERT –- an act of boundless courage, generosity, beauty, imagination, and wit -– presented us with a lot of heavy-duty shit: R.P.’s heart attack (expressed collectively by a chorus of different characters and voices, some of them white); R.P. shooting his wife’s car with a Magnum (the sounds of perishing tires and motor both lovingly recreated); his father’s death; whites and blacks crying differently at funerals; women R.P. has sex with who can’t come; R.P. getting beaten (with switches and fists, by grandmother and father), or finding roaches in his grandmother’s cooking. By contrast, LIVE ON THE SUNSET STRIP is a piece of cake, and he knows it. He also knows what he can do now, and that’s the major disappointment; in the earlier film, he was still discovering his capacities, finding his strength, and luxuriating in the power of that knowledge.

The new movie, much less funny and Shakespearean (and structured with all the apparent “spontaneity” of a fireside chat), is largely concerned with Pryor’s simple fears — of a black mass-murderer encountered at Arizona State Penitentiary, of whites who give rebel yells at night, of the chummy Mafia gangster he worked for at a nightclub in Youngstown, Ohio, when he was nineteen — and his simple day-to-day preoccupations (e.g., problems with money and lawyers, marital fidelity, memories of learning how to masturbate). His degree of candor remains admirable and touching; he even comments on his own nervousness about doing well, knowing how much is expected of him. Yet he mainly seems interested in keeping himself protected, under wraps -– like most of Susan Sontag’s writing since her own close brush with death. (“Canetti’s thought is conservative in the most literal sense,” she writes in her most recent collection of essays [Under the Sign of Saturn]. “It -– he -– does not want to die.”)

There are times when one can speak of Pryor as one spoke of Charles Mingus -– or as film theorist Raymond Bellour once wrote of Fritz Lang’s two Indian films, when he alluded to “an inability to lie carried to the point of tragedy”. Just as Lang’s refusal to gloss over the artificial joins in his sumptuous 1959 adventure spectacle foregrounds the simplicity of his childlike generic structure, Pryor’s aversion to slickness and predictability can sometimes keep him interesting and truthful in the most threadbare projects, even when it works against his material.

Up to a point, one can applaud his honesty in admitting that he’s grateful for prisons. But I’d much rather honor the primal directness of the following, from LIVE IN CONCERT, which tells me a lot more, with a touch of poetry besides: “If I’m walkin down the street, and I see a motherfucker laid out with slobber and shit hanging outa their mouth, they ain’t gonna make it….Cause you could be givin somebody mouth-to-mouth, and death could ease into your lungs.” There are no sentiments or images quite as stark as that in the newer film, which has more to do with simply laying low. Significantly, R.P. starts off by observing that “There’s not enough fuckin goin on in America” –- less under Reagan than under Carter -– and then goes on to talk about masturbation. (Reagan, alas, gets dropped.)

A trip to Africa provides Pryor with some of his best notions and routines; his physical and vocal embodiments of the “bad smells” that he and an African hitchhiker inflict on one another in a rented car is a masterpiece of insight and inflection. But when he describes his “magical experience” of deciding, upon leaving Africa, that “there were no niggers”-– realizing he hadn’t thought or spoken the word in three weeks, and promising that he’ll never use that word again –-his Born Again context puts me in mind of Malcolm X, in his great autobiography, dramatically and expediently staging his own enlightenment about racial harmony in Mecca some time after it actually took place. The feelings are both warranted and affecting, yet they’re too self-consciously and willfully “placed” here to convince entirely. Vowing never to say “nigger” (or to play Mudbone) again sounds suspiciously like a program for Pryor — and a trap. One feels that he’s trying to rise to the insuperable, quasi-religious demands that are being placed on him, and failing honorably.

His recounted tryst with a Playboy bunny, who makes him talk like a little boy while she undresses, perfectly illustrates the kind of infantile regression and retreat that were mastered earlier by Frank Tashlin and Jerry Lewis. “She gave birth to me about 9:30,” Pryor concludes. In LIVE IN CONCERT, he sketched out his metaphysics even more poetically: “My father died fucking. He did, man. He was fifty-seven and the woman was eighteen. He came and went at the same time. Didn’t nobody cry at his funeral.” Because in the one-man cinema of Richard Pryor, he who isn’t busy dying isn’t being born, either. And at his best, R.P. is always doing both.