This is the first thing I ever wrote about Ozu’s films. I’ve subsequently come to value Hen in the Wind much more than I did in 1972, above all as an expression of Japanese’s humiliation after the end of the war and during the American occupation. — J.R.

From Paris Journal, Film Comment, Summer 1972 (excerpt):

A recent screening of eight Ozu films at the Cinémathèque was, for Paris, an event of some importance. To date, not a single film by Ozu has received distribution in France, and local ignorance about his work extends to such places as Cahiers du Cinéma and Positif, which in their combined 368 issues have failed to publish a single article about him.

A particular revelation was WIFE FOR A NIGHT, which contradicted at least half of the received ideas that have been circulating about Ozu elsewhere. One of the ten silent films that he made in 1930, this remarkable American-style thriller begins and ends mainly in exteriors: a desperate robbery and escape at night, the criminal being led away at dawn. Virtually all of the intervening action is contained in the robber’s one-room flat, where he, his ailing daughter, his wife, and a policeman stand nervous vigil over one another for the night’s duration. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (December 23, 1988). — J.R.

The Puttnam Problem

Some of the year’s most ominous film-industry developments followed directly from the forced departure of David Puttnam as head of Columbia Pictures. During his brief and controversial tenure at Columbia, Puttnam — the outspoken Englishman who produced Chariots of Fire and other “quality” films — had attempted to reverse the overall trend in Hollywood of assigning more power and artistic control to stars and less to directors and writers by developing low-budget projects that weren’t completely subject to the whims of stars and their agents.

After Puttnam’s departure, the desire to discredit his strategies at Columbia was so pronounced that most of his projects were deliberately sabotaged through a flagrant lack of promotion — demonstrating once again that the major aims of Hollywood are often not so much the making of money as the fulfillment of various personal forms of vanity. (Bill Forsyth’s Housekeeping is a good example of the sort of serious Puttnam project that was virtually foredoomed at the box office by the pressure of anti-Puttnam sentiments.) Adding insult to injury, a series of anti-Puttnam articles appeared in the trade magazine Variety, which attempted to appease Puttnam’s enemies by demonstrating that his films were commercially unsuccessful, conveniently overlooking the fact that very few of them were given even a sporting chance to succeed. Read more

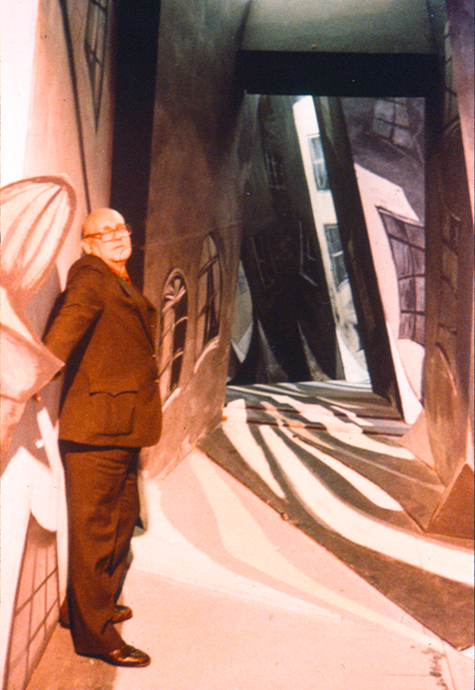

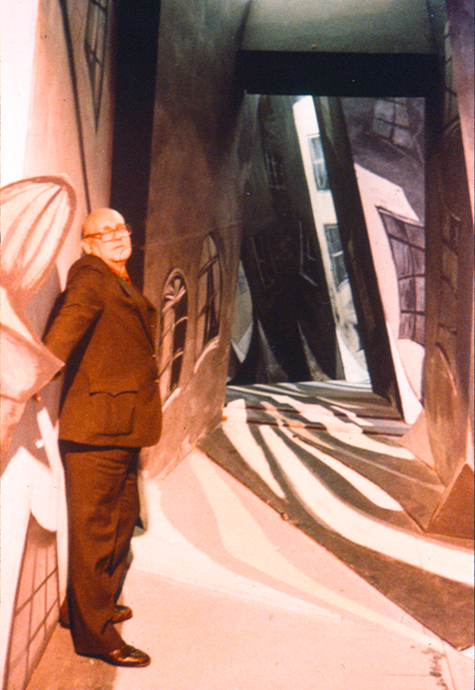

Thanks to a passing reference by Andy Rector on Girish’s excellent blog, I’ve just stumbled upon an invaluable online reference tool — the William K. Everson Collection, which has been set up by New York University’s Cinema Studies, where Everson taught from 1972 to 1996. As someone who used to attend some of the memorable screenings of The Theodore Huff Memorial Film Society that were organized by Everson, at two or three of its separate locations, I’m especially delighted to recover some of the program notes he wrote for those events, such as those for F.W. Murnau’s rediscovered City Girl (a screening I attended) on March 2, 1970. In fact, the two most impressive individual archives to be found at this site are Everson’s voluminous program notes, beautifully cross-referenced and reproduced for easy access, and his collection of press kits. (There are also some other things here as well — including the photograph reproduced above, of Everson imitating Cesare in the Cabinet of Dr. Caligari set that was rebuilt inside the Cinémathèque Française’s Musée du Cinéma at the Palais de Chaillot.)

Everson’s immense value when he was alive was more his extraordinary generosity, the breadth of his knowledge as a film scholar, and his enthusiasm than his critical acumen, so there are times when one wants to quibble with some of the own opinions in his notes (such as his own quibbles about Jacques Tourneur’s masterpiece Stars in My Crown, for example). Read more

From The Movie, Chapter 65, 1981.-– J.R.

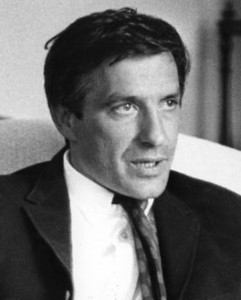

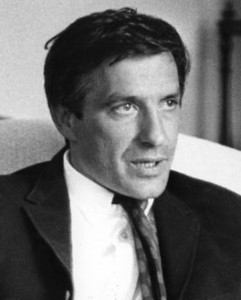

One of the most paradoxical and controversial of all the American independents, John Cassavetes has always placed actors and acting at the center of his film-making conceptions. An actor himself, he has used his craft as a means of financing his own productions — which are themselves celebrations of acting. ‘Directing really is a full-time hobby with me,’ he confessed in an interview in the late Sixties. ‘I consider myself an amateur film-maker and a professional actor.’

Born on December 9th, 1929 in New York City, the son of a Greek immigrant who made and then lost a fortune in business, Cassavetes attended Colgate College as an English major. It was there that his interest in acting was sparked, and he enrolled in the American Academy of Dramatic Arts shortly after graduation.

Delinquent turns director

Following a stage debut in a stock company and a bit part in a Hollywood feature, Fourteen Hours (1951), Cassavetes gradually acquired his reputation as a young actor by appearing in television dramas, where he specialized in juvenile delinquent parts. By the mid-Fifties, budget, he was re-creating one of these roles in a film about a family being held captive by hoodlums, The Night Holds Terror (1955). Read more