The BBC has just asked me for this list. I took care to split this evenly between fiction and non-fiction. — J.R.

1. The House is Black (Forough Farrokhzad, 1963)

2. The Enchanted Desna (Yulia Solntseva, 1964)

3. Mix-up ou Méli-Mélo (Françoise Romand, 1986)

4. Vagabond (Agnès Varda, 1985)

5. The Asthenic Syndrome (Kira Muratova, 1989)

6. Passionless Moments (Jane Campion, 1983)

7. From the Other Side (Chantal Akerman, 2002)

8. You Are Not I (Sara Driver, 1981)

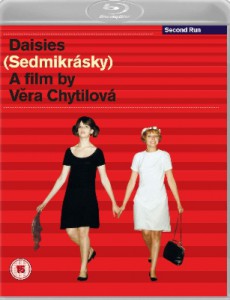

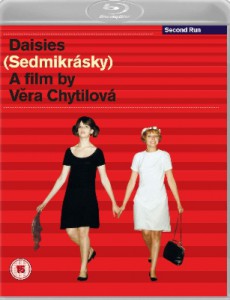

9. Daisies (Vera Chytilová, 1966)

10. Aragane (Oda Kaori, 2015) Read more

From the Chicago Reader (December 1, 1995). — J.R.

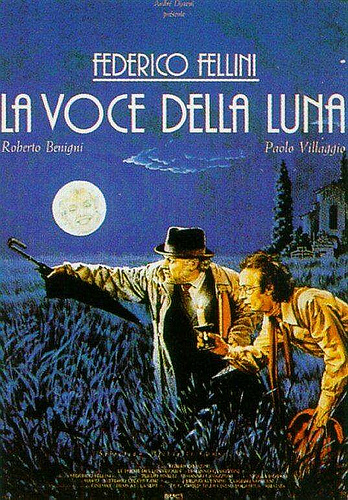

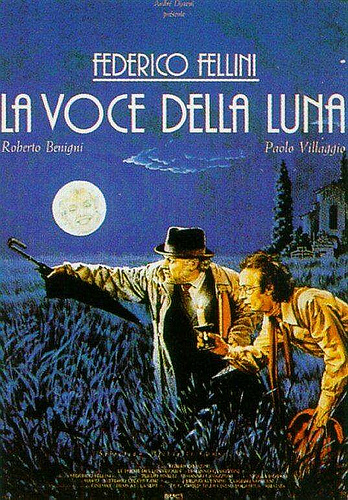

The Voice of the Moon

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Federico Fellini

Written by Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, and Ermanno Cavazzoni

With Roberto Benigni, Paolo Villaggio, Nadia Ottaviani, Marisa Tomasi, and Angelo Orlando.

Casino

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Martin Scorsese

Written by Nicholas Pileggi and Scorsese

With Robert De Niro, Sharon Stone, Joe Pesci, James Woods, Don Rickles, Alan King, Kevin Pollak, and L.Q. Jones.

If I had the choice of seeing either Martin Scorsese’s latest (Casino) or Federico Fellini’s last (The Voice of the Moon) a second time, I’d opt for the Fellini. Both films are relatively minor works by relatively major filmmakers, though Scorsese has described The Voice of the Moon as one of Fellini’s “better pictures.” But Fellini’s swan song has a sweetness and sadness because it represents a kind of local — that is to say national — filmmaking that seems to be quickly vanishing from the mainstream. It isn’t hard to understand why no U.S. distributor has picked up this 1990 movie: it’s too Italian, and it isn’t at all easy to follow as storytelling, because it digresses all over the place. Yet these qualities, which are part of the film’s charm and poetry, might have worked in its favor outside Italy 30 years ago, when audiences tended to be more curious about other cultures and other forms of storytelling. Read more

It would obviously be hyperbolic for me to claim that the editorial evisceration originally suffered by this article was comparable to some of the curtailments experienced by Richard Pryor when he appeared on TV or in the Hollywood mainstream, but that’s more or less what it felt like to me at the time. I recently and very belatedly uncovered all but the last paragraph or so of my original version (after posting mainly the published version several months earlier), which I’ve reinstated here [on November 14, 2011]. The fact that the editor who placed this article in a lead section of Film Comment’s July-August 1982 issue entitled “The Coarsening of Movie Comedy” also changed my title to “The Man in the Great Flammable Suit” may give some notion of what his evisceration felt like at the time.

My working assumption in restoring original drafts on this site, or some approximation thereof, isn’t that my editors were always or invariably wrong, or that my editorial decisions today are necessarily superior, but, rather, an attempt to historicize and bear witness to my original intentions. It was a similar impulse that led me to undo some of the editorial changes made in the submitted manuscript of my first book, Moving Places: A Life at the Movies (1980), when I was afforded the opportunity to reconsider them for the book’s second edition 15 years later (now out of print, but available online here) — not to revise or rethink my decisions in relation to my subsequent taste but to bring the book closer to what I originally had in mind in 1980. Read more