This appeared in the Chicago Reader on April 26, 1991. Consider this review Part 2 of a long-term re-evaluation of Alan Rudolph’s use of music and his treatment of working-class people, preceded by my 1979 review of Remember My Name for Film Quarterly. — J.R.

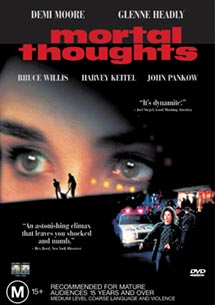

MORTAL THOUGHTS

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Alan Rudolph

Written by William Reilly and Claude Kerven

With Demi Moore, Glenne Headly, Bruce Willis, Harvey Keitel, John Pankow, and Billie Neal.

For all his talent and sophistication, Alan Rudolph has frequently shown a romantic slant toward the working class that borders on stylistic gentrification. Even in my two Rudolph favorites, Remember My Name (1978) and Choose Me (1984), the ironic casting of a construction worker and his wife with real-life mod couple Anthony Perkins and Berry Berenson and the creation of a dream-bubble ambience in a gritty bar suggest a kind of put-on.

Life is a dream, Rudolph always appears to be saying, and the more sordid and low-down the life is, the more seductive and precious the dream becomes. It’s a viable enough premise for a mannerist, and he invariably makes the most of this conceit; yet there are times when his taste for cardboard funk causes his worlds to totter like houses of cards. Welcome to L.A. (1976), Trouble in Mind (1985), The Moderns (1988), and Love at Large (1990) all display at least momentary signs of this shakiness; enjoyable as they all are, they never quite transcend their charm as stylistic exercises.

The half dozen Rudolph films I’ve mentioned so far were all written by him, as was the anomalous Endangered Species (1982). Return Engagement (1983) was a documentary about G. Gordon Liddy and Timothy Leary, and four others — Roadie, Songwriter, Made in Heaven, and now Mortal Thoughts — qualify as inherited projects. (Early on, he directed two horror pictures, which he disowns and I haven’t seen.) In the case of Mortal Thoughts, written by William Reilly and Claude Kerven, he returns to a working-class milieu, but this time the possibilities of romantic embellishment are virtually nonexistent. The result is a strong and gripping picture that nonetheless leaves me ambivalent.

Music is almost always a main ingredient in a Rudolph picture; at least three of them–Welcome to L.A., Remember My Name, and Choose Me — essentially began as record albums around which Rudolph shaped narratives and visual styles. Ever since Trouble in Mind, he has worked with a new-age/fusion composer and musician named Mark Isham, and in certain respects the centrality of the role played by Isham’s scores rivals that played by the camera. This becomes especially important in Mortal Thoughts, where the story, characters, and settings are restricted to a working-class milieu — the film was shot in New Jersey, in Bayonne, Hoboken, and Jersey City — and the music clearly belongs to another realm entirely. It creates a voyeuristic distance between ourselves and the characters, establishing a rigid polarity of “us” and “them” that no amount of sympathy can wholly cross.

My father, a literature professor, used to argue that the novel was an invention that made it possible, for the first time in history, for those in the middle and upper classes to imagine what it was like to be someone in a different milieu. Before the novel came along, it was socially acceptable to visit insane asylums for entertainment; the very notion that such an attitude might be cruel and inhumane became feasible only after novels made it possible to consider an inmate’s point of view.

A quarter of a century ago, the prevailing liberal-humanist ideology in this country appeared to be that as the world steadily shrank through the growth of communications, racial, ethnic, and economic differences between people became less and less important. Fed in part by Marshall McLuhan’s utopian vision of the “global village” supposedly made possible by television, the overall idea resembled an extension of my father’s theory about the novel: the more massive and widespread mass culture became, the more we learned about peoples and cultures different from our own, and the more we learned, the less we had to fear. Perhaps I’m oversimplifying the optimism of the mid-60s, but the gist of this attitude was that mass communications were good because they collapsed both geographical and cultural differences.

The problem with this attitude is that it uncritically assumes that mass communications communicate, while overlooking the ways in which they might do the reverse by reinforcing language barriers and other cultural differences. (In a similar fashion, phone-answering machines could just as accurately be called phone-nonanswering machines because they serve to block as well as facilitate communication.) Today, when we’re probably more cynically aware of the role played by mass communications in selling products — material or ideological — we’re more likely to believe that the reverse of McLuhan’s optimistic hypothesis is true. In terms of the recent war in the Middle East, for instance, mass communications made it possible to believe that the slaughter of tens of thousands of innocent people was less important than the proud victory of a beleaguered world power suddenly feeling its oats again. It even became possible to celebrate the spectacle of an elephant stepping on a flea, because the subject of the mass communications was the size, health, and efficiency of the elephant’s foot, not the welfare of the flea underneath.

All this may seem pretty extraneous to a consideration of a crime thriller set in New Jersey, but I think it has immediate bearing on the role played by Isham’s music in the film. The problem isn’t that Mortal Thoughts is condescending or inhumane or unfeeling toward its characters: on the contrary, it draws us into the worst of their problems with a great deal of compassion and understanding. But it never, not even for an instant, allows us to make the leap that a novel or short story by, say, Nelson Algren would, in order to imagine that these events could happen to us or people close to us.

The plot of Mortal Thoughts depends on various delayed revelations and surprises, the last of which, while it violates our faith in the narrative as a whole, doesn’t substantially alter our overall sense of the characters. The story unravels as a series of flashbacks during the interrogation of Cynthia (Demi Moore), who’s brought to a dingy police station for questioning by two detectives (Harvey Keitel and Billie Neal) when her best friend Joyce’s husband is found murdered.

The emotional center of the film is the friendship between Cynthia and Joyce (Glenne Headly), both young mothers, and the dramatic tension derives from various forces — societal as well as personal — that threaten their friendship. In flashbacks, Joyce’s unemployed husband James (Bruce Willis) is seen as a sexist lout and tyrant who spends most of his time getting high, beating and abusing Joyce, and making crude passes at Cynthia — a character with no redeeming qualities whom the film makes no attempt to soften or excuse. Joyce despises him but seems unable to break away from him, and we learn that their mutual antagonism as a couple dates at least as far back as their wedding, though according to Cynthia, Joyce regarded him as a prize “catch.”

In short, the relationship between Joyce and her husband is both ineffable and familiar; so is their awful milieu. The principal actors — Moore (who coproduced the film), Headly, Willis, and Keitel — are all uncommonly good at making these characters, particularly their speech and accents, immediately recognizable as well as believable, and the locations are equally dead-on. The grim, tacky interiors — including a funeral parlor, the characters’ homes, and Joyce’s Clip ‘n’ Dye Beauty Salon — are brutally plausible.

Yet in spite of these attributes, I couldn’t shake off a phrase I kept recalling from critic Manny Farber — whose original occasion I don’t remember, but whose aptness here is hard to resist: “oily overdefinition of the working class.” The film not only lingers on those aspects of the milieu that lend themselves most easily to satire — a wedding band’s corny rendition of Billy Joel’s “Just the Way You Are,” James’s misspelling of the word “sugar,” Joyce’s bubble-gum snapping, the bad art in the funeral parlor — but it also gives us such a safe and untroubled vantage point that we never respond to the characters’ dilemmas as if they resembled in any way our own.

I have no quarrel per se with the film’s detachment from its characters. Rudolph generally avoids the kind of condescension that has often sabotaged other projects of this kind, and an important part of the movie’s effectiveness in fact depends on its creation of an analytical distance between ourselves and the world that’s being shown. (Similar distancing strategies were used less effectively in True Love [1989] — an independent feature by Nancy Savoca about the preliminaries to a loveless, hopeless marriage of a couple in Brooklyn in which the lack of empathy for any of the characters and the absence of a compelling plot blunted the film’s satirical aspirations.) Cynthia and Joyce’s friendship is treated sympathetically throughout, and this encourages us to analyze all the horrific elements in their environment that ultimately alienate them from each other in spite of their good intentions.

Indeed, our analytical distance suggests at times that much-abused descriptive term “Brechtian”: not only are we distanced from the characters in order to understand certain things about them, but we are also being entertained in the process. One of Rudolph’s central props is a TV monitor that frames Cynthia frontally during her interrogation. Keeping his camera in almost constant motion, circling the three characters and the nearby monitor, Rudolph is at his best when he adroitly shuttles back and forth between the interrogation and the various portions of the story that Cynthia is telling; the TV monitor is only one of his more obvious ways of activating an analytical perspective on what we’re watching. A master at establishing contemplative registers, he makes remarkable use of slow motion at the beginning of several sequences, and he also knows when to jerk us back to attention with an abrupt cut. Purely as an exercise in story telling, Mortal Thoughts is in some ways as impressive as anything he’s done.

Yet the film leaves me with a queasy feeling — almost exclusively the product of Isham’s subtle and effective score — that just won’t go away. With its wordless ethereal voices, its muted and unmuted brass, its purring Gil Evans-like harmonies and voicings, and its varied uses of “soft” percussion (which include a suggestion of heartbeats at one climactic juncture), the music sets up an impenetrable glass wall between us and the characters — at once distancing and reassuring — that we instinctively know from the outset will never be broken. (The fact that we can’t imagine any of the characters in the movie listening to this kind of music with pleasure is not only symptomatic but emblematic of this barrier.) Admittedly, this knowledge of our safety and security is what makes all the other elements in Rudolph’s style mesh and register; the film’s overall achievement, such as it is, would be unrealizable without it. But unlike the warmth and intensity that Algren’s poetic prose weaves around lives that are equally blighted and hopeless, Isham’s score makes the possibility of loving these characters or feeling morally committed to them not only impractical but unthinkable.