From the December 15, 2000 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

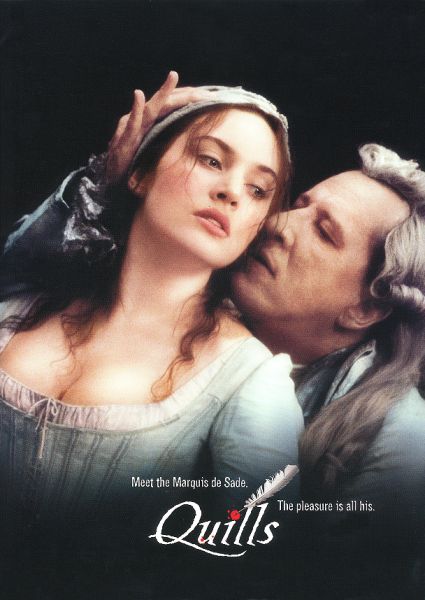

Quills

***

Directed by Philip Kaufman

Written by Doug Wright

With Geoffrey Rush, Kate Winslet, Joaquin Phoenix, Michael Caine, Billie Whitelaw, Patrick Malahide, and Amelia Warner.

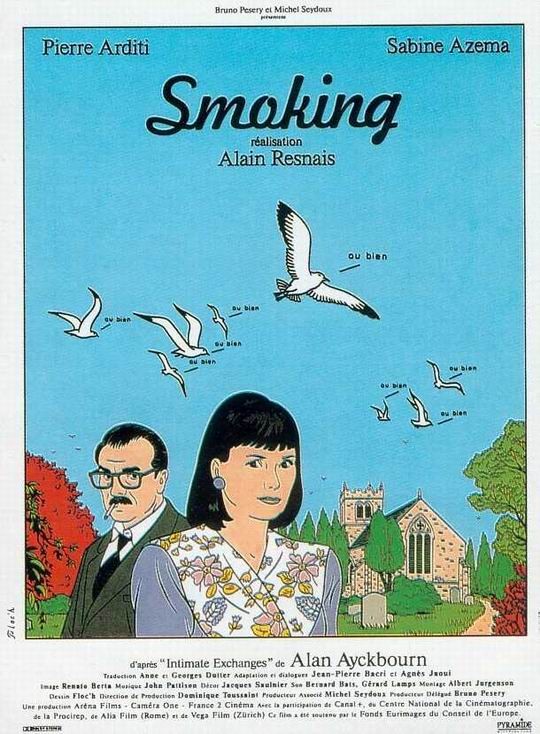

Smoking

***

Directed by Alain Resnais

Written by Alan Ayckbourn, Jean-Pierre Bacri, Agnès Jaoui, and Anne and Georges Dutter

With Pierre Arditi and Sabine Azéma.

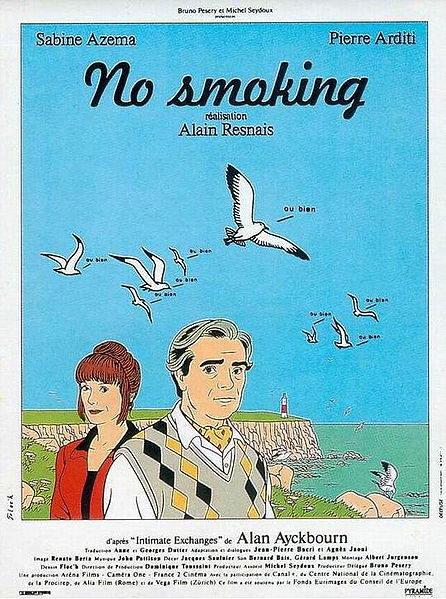

No Smoking

***

Directed by Alain Resnais

Written by Alan Ayckbourn, Jean-Pierre Bacri, Agnes Jaoui, and Anne and Georges Dutter

With Pierre Arditi and Sabine Azema.

Quills is an American adaptation of an American play about the famous 18th-century French libertine the Marquis de Sade, starring Australian, English, and American actors. It is also, in part, an unacknowledged mainstreaming of a more intellectual German play that became famous in the mid-1960s because of an exciting and inventive staging by avant-garde English director Peter Brook — Peter Weiss’s The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade, popularly known as Marat/Sade. (Brook’s 1966 film adaptation of this intensely theatrical play is a pale shadow of the original.)

Smoking and No Smoking — not a double bill but a pair of interactive features that can be seen in either order, both playing at Facets Multimedia Center this week — are French adaptations of a cycle of eight mainly comic English plays by Alan Ayckbourn. The plays are set exclusively in Yorkshire exteriors and are designed to be performed by only two actors in multiple roles over eight consecutive evenings, though this has never been done anywhere. Each of the plays has two endings, making 16 variations in all. For the films, that number has been reduced to 12 by eliminating the two plays in the middle of the series, which deal with the most “typically English” subjects — a medieval pageant and a cricket match. Smoking, which adapts the first three plays, charts events that ensue at regularly spaced intervals after a housewife decides one morning in early summer to smoke a single cigarette. No Smoking, which adapts the final three plays, also leapfrogs across time to show the apparent consequences of her decision not to smoke the same cigarette. The amount of time that lapses between scenes begins at five seconds, then shifts to five days, five weeks, and five years. Different decisions made at each juncture eventually lead to a dozen separate conclusions.

Both films center on an alcoholic headmaster, Toby Teasdale, and his shy wife Celia, and their interactions with, among others, the school’s night watchman, Lionel Hepplewick, and a housekeeper, Sylvie Bell. There are nine characters in all — five women and four men.

Why has this pair of films taken seven years to reach Chicago — especially given that they swept the Césars, the French Oscars, in 1994 (winning best picture, director, actor, screenplay, and set design) and triumphed both critically and commercially in France? Because some English and American viewers find their highly stylized and deliberately stagy French versions of English characters and settings difficult to swallow. As critic Richard Combs put it, “The perversity is that this is not Ayckbourn reinterpreted as a French play, but Ayckbourn speaking French while still pretending to be English, with a confusing screen of different body languages and physical types.”

We can’t know what the French response to Quills will be, because the film is opening here only this week. But I’d be surprised if many French viewers could process its characters, settings, and premises without blanching. Paraphrasing Combs, one might say that this isn’t Sade reinterpreted as an American hero, but Sade speaking English while still pretending to be French.

For better and for worse, all three films depend on cultural misunderstandings — some undoubtedly more deliberate than others — which gives them much of their novelty and interest. The cultural clashes in them are every bit as notable as the convergences, and how much you like any of these films will have a lot to do with how you balance these ideas and how much you can inhabit their imaginary spaces.

It’s serendipitous that these works are turning up in Chicago the same week, but I find their diametrically opposed and complementary natures fascinating. Quills is directed by Philip Kaufman, a particular favorite of the now-retired film critic Pauline Kael and her many disciples. No Smoking and Smoking are directed by Alain Resnais, possibly the least favorite French filmmaker of distinction among the same group of critics. Broadly speaking, I think Kaufman is popular with Kael and her followers because many of his films are entertaining and sexy in spite of their intellectual trappings and aspirations. And I suspect that Resnais is unpopular with them because of his formal concerns and his sense of abstraction and because his films, though highly accomplished as art, often aren’t very entertaining. I would describe Quills as uninteresting as thought or art but quite entertaining, and Smoking and No Smoking as quite interesting as art and somewhat interesting as thought but not especially entertaining. (In the December Artforum, Susan Sontag puts the two Resnais films at the end of her ten-best list, calling them “brilliant, ingenious, hilarious”; I’d agree at least with the first two adjectives.)

I hasten to add that separating art from entertainment is something Americans do a lot more than French people, who are apt to use such blanket terms as “pleasure” to cover both. And my subjective impressions shouldn’t necessarily be taken as consumer advice. I have no doubt that some Americans will find Resnais’ two features highly entertaining, while others will want to flee after having just a taste. And I wouldn’t be surprised if some viewers find Quills intellectually invigorating.

Some of Resnais’ American detractors have accused him of being an intellectual; Resnais has denied it, and I tend to support his disavowal. All of his films might be called culturally refined and Cartesian, in the sense that they’re largely about the life of the mind, but they generally aren’t interested in exploring ideas in depth. In all of his work — from Hiroshima, mon amour, Last Year at Marienbad, and Muriel (his first three features) to Providence, Mélo, and Same Old Song (three of the later ones) — feelings play a much more important role. It’s worth considering that his love of comic strips (which finally found a limited outlet in his least seen and perhaps most underrated feature, I Want to Go Home, scripted by cartoonist Jules Feiffer) and of Stephen Sondheim (whom he hired to write the score of Stavisky) isn’t expressed as an intellectual enthusiasm. It’s also worth considering that Americans, unlike the French, tend to see mind and feeling in opposition, which can lead to different definitions of what intellectuals are.

Kaufman, by contrast, seems to consider himself an intellectual, and his fans seem inclined to agree, clearly seeing nothing denigrating in the label — though presumably regarding him as a “fun” intellectual in comparison to someone like Resnais, meaning that he’s smart and cultured without being distant or pretentious. Kaufman’s brief essay that opens the press book does quote, in swift succession, “my old friend Nelson Algren,” “Algren’s friend Simone de Beauvoir,” “Nobel Prize winning poet and essayist Octavio Paz,” and “the great film director Luis Buñuel,” but these citations all come much closer to “plain talk” than intellectual explorations. Admittedly, Marat/Sade onstage had some intellectual content, but it was designed mainly as a feast for the senses; in many ways Quills offers a more middlebrow and distinctly post-60s version of that experience, without the French Revolution.

An enormous literature has accumulated around the figure of Sade as an emblem of freedom and of perversion. Much of the French writing, from de Beauvoir to Michel Foucault and Roland Barthes, is concerned with celebrating the formal and theoretical aspects of this freedom, while much of the American writing, from Edmund Wilson in The Bit Between My Teeth to Roger Shattuck in the recent Forbidden Knowledge, is concerned with condemning the moral and ethical aspects of the perversion underlying it. This debate has been raging for so long and in so many different forms that it can even be said to inflect many nonintellectual sectors of French culture. It’s worth adding that many years ago Resnais developed but never realized a film about Sade, written by an American, Richard Seaver, who translated much of Sade into English; and it seems possible that Barthes’ Sade/Fourier/Loyola (1971) influenced the utopian preoccupations of Resnais’ 1983 Life Is a Bed of Roses (recently revived at the Film Center).

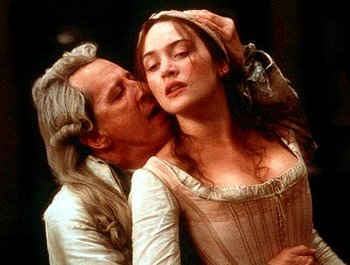

Given this debate, which I’ve read more of than of Sade himself, the curious thing about Kaufman’s movie, and presumably Doug Wright’s source play, is that it celebrates Sade’s notions of freedom without engaging the moral and ethical issues arising from them — at least not in any way that might disturb or challenge the audience. To put it simply, Kaufman and Wright Americanize the marquis (Geoffrey Rush), turning him into a classic antiauthoritarian and adolescent-minded anarchist hero, a martyr of free expression who will go on writing his politically incorrect sexual fantasies no matter what, even with his own blood and shit if necessary. Furthermore, they give us such an obvious and unambiguous villain to oppose him — Dr. Roter-Collard (Michael Caine), the hypocrite and closet sadist who runs Charenton, the mental asylum where Sade is being held — that no serious challenge to Sade’s moral position is even contemplated, much less explored. He’s simply a stand-up-comic sort of guy, bristling with witty bons mots that wow all the attractive and available ladies in sight, whereas the doctor has to revert to force to procure his child bride, who reads Sade’s Justine on the sly.

Paradoxically, the only real perversion or cruelty or sadism belongs not to Sade, an absolute hero and dashing bon vivant, but to the doctor, an evil authoritarian who serves as the rough equivalent of Big Nurse in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (though Quills doesn’t have that book’s misogyny — Kaufman, to his credit, actually likes women). Yet to give us the impression that a true debate of Sadean issues is nevertheless in progress, the film also offers a relatively equivocal in-between figure, Abbe Coulmier (Joaquin Phoenix), around whom a good part of the drama is structured — a character who stands officially on the doctor’s side while sympathizing increasingly with Sade and wrestling with his own inner demons of desire and repression.

This simplistic view would make me livid if I cared more about the integrity of Quills and its fidelity to history, including intellectual history — as much as I care, say, about the integrity of the Coen brothers’ forthcoming O Brother, Where Art Thou? and its fidelity to Mississippi, the Depression, the popular front, the Ku Klux Klan, William Faulkner, and Preston Sturges. What, after all, could be more absurd than a cuddly Marquis de Sade? Instead of being livid, I quickly decided I preferred to be entertained by Kaufman’s sexiness and silliness — Quills is a guilty pleasure I chose to indulge.

So I was impressed by the lively performances — including those of Kate Winslet and Billie Whitelaw and the actors already mentioned — and I was amused by the witty if simpleminded plot and dialogue, not to mention Kaufman’s assured storytelling. If he and Wright want to make hash of the entire Sade debate in order to show us a good time, why not? The distinction between hero and villain may be about as stark as in a Gene Autry western — undermining many of this movie’s intellectual claims and shamelessly flattering the audience’s sense of righteousness — but who says entertainment has to be intellectually challenging? (By contrast, when I saw Kaufman’s much-praised and equally sexy film adaptation of Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being in 1988, I couldn’t get past how he’d perverted the novel, avoiding what Kundera had to say about kitsch and any aspect of Czech life Americans didn’t already know about. Does that mean I value Kundera more than Sade? Maybe.)

I suppose that being entertained by Quills was an intellectual — or anti-intellectual — choice on my part. And viewers can make a similar choice. Even those unacquainted with or indifferent to the Sade debate and French history don’t have to worry; they can simply see Quills as a slightly more thoughtful and reflective Indiana Jones or Sean Connery romp. (Kaufman collaborated on the story of Raiders of the Lost Ark and directed Rising Sun, which featured Connery.)

I’m devoted to Resnais, and so I’ve spent a lot of time with Smoking and No Smoking. Yet I’m still not sure how much they’ve rewarded my attention. After seeing a Paris press show of Smoking in 1993, where I couldn’t follow some portions of the dialogue without subtitles, I combed bookstores in at least three countries before I found Alan Ayckbourn’s Intimate Exchanges, the cycle of plays Resnais had translated by one couple (Anne and Georges Dutter) and adapted by another (the much better known — and more prominently credited — Jean-Pierre Bacri and Agnès Jaoui, who later wrote and acted in Resnais’ Same Old Song). A couple of years later, after seeing one of the films subtitled, I bought unsubtitled French videos of both — packaged together attractively in a blue box that, appropriately enough, is the size of a board game and is decorated with some of the cartoon drawings and settings by French artist Floc’h that punctuate the films — and endeavored to follow them with the aid of the plays.

I can now see that all this scholarly effort was probably misplaced, considering that these two features are, after all, intended mainly as a lighthearted experiment to be pursued in a spirit of fun — a virtuoso piece for two very skillful (if mannered) actors (two Resnais regulars, Sabine Azéma and Pierre Arditi) that delights in artificial sets and fanciful musings about the unexpected curves lives take over several years. An unfortunate consequence of my exertions is that the films have lost part of their magic for me, though I have to say I always admired more than relished them. The brittleness of the jokey English details is a far cry from the theatricality of Mélo — for me the greatest of Resnais’ late films — and the play with narrative conventions, an essential part of his earlier work, develops without the powerful musical rhythms he used to derive from his editing and tracking shots. The thematic links with some of his other films are somewhat clearer. His interest in national stereotypes — also found in his previous feature, I Want to Go Home, about both the American fascination with French culture and the French fascination with American culture — seems to bring him full circle to Hiroshima, mon amour, which focused on a Japanese architect and a French actress, both partly conceived as national archetypes, who have a brief affair in Hiroshima.

That the characters in Smoking and No Smoking are neither English nor French but freakish hybrids makes them at times fascinating theoretical constructs more than characters whose fates engage me, even though the elaborate and stagy studio sets do engage me; they seem not only inhabitable but large enough to get lost in. This is the sort of paradox one often finds in Resnais’ work, which can sometimes seem obsessively involving and oddly remote at the same time (as in Marienbad). Still, following the alternate plots of both movies is a provocative and highly involving process, and there’s no question that they offer a narrative adventure unlike anything you can find at the multiplexes, including Quills — which might be described as the usual fun and games by comparison, however lively.

Given the French preference for pleasure over denial, it’s probably no surprise that French viewers who picked only one feature opted more often for Smoking, and Charles Coleman, the programmer at Facets, is honoring this bias by scheduling No Smoking five times and Smoking six. I find it impossible to recommend one feature over the other, and I’ve yet to encounter any reviewer who expresses a preference. Moreover, if you had to choose between Smoking, No Smoking, and Quills, I wouldn’t even begin to know how to advise you.