This was originally published in the July 1976 issue of the Monthly Film Bulletin (vol. 43, no. 510), to coincide with the release of Hitchcock’s Family Plot (illustrated on the cover, and reviewed in that issue by the editor, Richard Combs). — J.R.

Ring, The

Great Britain, 1927

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

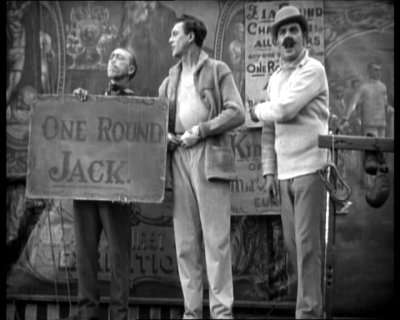

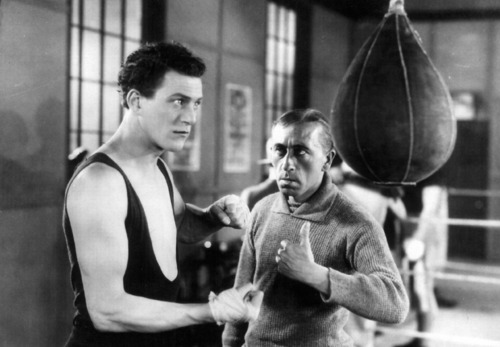

Dist—BFI. p.c–British International Pictures. p–John Maxwell. asst. d—Frank Mills. story/sc—Alfred Hitchcock. continuity—Alma Reville. ph—John J. Cox. a.d—Wilfred Arnold. l.p—Carl Brisson (“One Round” Jack Sander), Lillian Hall-Davies (Nelly), Ian Hunter (Bob Corby), Forrester Harvey (Harry), Harry Terry (Barker), Gordon Harker (Trainer), Billy Wells (Boxer). 3,179 ft. (at 16 f.p.s.) 132 min. (16mm). Original 35 mm footage—8,400 ft.

At a traveling circus, prizefighter “One Round” Jack Sander is knocked out and defeated for the first time in his show by Bob Corby, an Australian heavyweight, and a mutual attraction develops between the latter and Nelly, Jack’s ticket-seller fiancée. With his prize money, Bob buys Nelly an arm bracelet which she hides from Jack, and Bob’s manager offers Jack the chance of a job as the champion’s sparring partner if he wins a trial match, which he grudgingly accepts. The next day, when Nelly’s bracelet accidentally falls in a pond and Jack retrieves it, she explains it is a gift from Bob, and he slips it on to her finger, proposing that they marry when he returns from the trial match. He wins the fight, and they have a church wedding with their circus friends and Bob and his manager attending. But afterwards her flirtation with Bob continues unabated, and Jack broods increasingly about his own inferior position. Told by Bob’s manager that he has a chance to become champion if he defeats Kid Gunn, a black fighter, and leaves Nelly to go into training, and wins the match. But when he returns home with his circus friends to celebrate, Nelly is out partying with bob. When she comes home late, she and Jack quarrel and Jack goes out, finds Bob in a night-club and knocks him down, challenging him to formal match; when he returns home, he discovers that Nelly has left him. But she returns to watch the climactic fight and eventually gives all her support to Jack, who knocks Bob out after several rounds, reunited with Jack, she abandons her bracelet, which is found by Bob’s friends beside the empty fighting ring.

Made not long after his visits to Berlin and Munich in the mid-Twenties, The Ring is probably the most Germanic in style of Hitchcock’s silent films; in terms of its technique and elaborate formal symmetries, it is also arguably the one that is worked out most conscientiously in strictly film terms. Recalling the applause that greeted one of its montage sequences, the director is fond of terming it the second real “Hitchcock picture” after The Lodger — despite the fact that it eschews suspense for most of its running time, and was more a critical than a commercial success; significantly, it is the only film in his career with an original script credited to himself alone. Fluid without being at all fast, the film emerges as something closer to a contemplation than an exposition of its subject: as Raymond Durgnat aptly notes, “A potentially strong conflict…is so handled as to avoid, for long periods, any easily climactic confrontation, and so produces something more petty, edgy, unnerving”. With a dramatic situation which mainly remains static between the opening and closing fights, the film’s expressiveness is thus largely restricted to its formal repetitions, bracketed by a consideration of the mechanisms of spectacle whereby prizefighting becomes a virtual metaphor for the cinema itself –- a role assumed rather differently by the séance in Family Plot, half a century later. Although the cruel bloodlust of the crowds is only made apparent in the two major fight scenes, it is sufficiently underlined there to affect one’s reading of all the intervening events. At the first, Jack Sander’s trainer (Gordon Harker — a splendid deadpan type suggesting a cross between Hoagy Carmichael and Percy Kilbride) blandly holds out Bob Corby’s jacket, expecting the challenger to be flattened at short notice; at the second, a bored spectator with a cigarette holder resignedly puts on his own dinner jacket, with the equally false expectation that Sander is on the verge of collapse. The fact that the former occurs under a circus tent, and the latter in a theatre complete with box seats, emphasizes the spectacle’s universality, and the prominence given to cameramen filming the second event broadens the metaphor to include Hitchcock’s own medium. A lighter aspect of spectacle comes to the fore at the delightful wedding ceremony – where the doubling images include Siamese twins vying for seats in opposite pews and a button accidentally replacing the wedding ring, and the view of spectators here and immediately afterwards (e.g., Harker’s ‘drunken’ focus at the marriage feast) registers less cynically. But an early episode showing a boy throwing an egg at a clown leaves little room for doubt about the director’s usual view of audiences; and it is worth recalling that the celebrated recurrences of ‘ring’ images in the film – circular rides at the carnival, boxing ring, bracelet and the marriage band – also include the spinning roll of tickets sold when Corby starts to give Sander a fight for his money, and the barker exploits this fact to attract bystanders. Other formal repetitions, including images of desire or humiliation, suggest exchanges between the antagonists within this wider context: Corby’s first glimpse of Nelly, in long shot, is superimposed with a dreamlike camera movement towards her face in close-up, and Sander’s climactic visualization of her infidelity with Corby, framed in a mirror, is represented almost identically; Nelly’s view of Sander’s initial defeat, caught over the crowd’s shoulders, is echoed by Sander’s sudden glimpse of her over Corby’s shoulder while nearly passing out in the final match. Early kissing scenes between Nelly and each man are cut in the same manner – from medium-shot to close-up and back again – although the second, with Sander, is pointedly made shorter and less passionate. Like the reflection of Nelly and Sander in a pond that is repeated as a memory image in Sander’s water bucket at the final bout, all these symmetries translate ways of looking into modes of feeling, with a sensitivity rare for Hitchcock during this period. If the formalism occasionally suggests a sense of determinism about the characters’ fates — an intimation embodied by a circus fortune-teller who seems to step straight out of Kammerspiel — the unexpected happy ending alters this impression somewhat by absolving the plot of evil intentions: to all appearances, the defeated Corby seems to wish the couple well, and in retrospect most of the film’s darker elements seem to relate less to facts than to subjective states of mind. But framing this ambiguous terrain are the ironclad laws of spectacle itself, where triumph or defeat becomes a wholly objective matter — an overlit stage where all the consequences of status are determined, and a fighter’s life is legislated for the sake of an evening’s entertainment.

—Monthly Film Bulletin, July 1976