From the Chicago Reader (July 11, 1997). — J.R.

Men in Black

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Barry Sonnenfeld

Written by Ed Solomon

With Tommy Lee Jones, Will Smith, Linda Fiorentino, Vincent D’Onofrio, Rip Torn, Tony Shalhoub, and Mike Nussbaum.

Contact

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed by Robert Zemeckis

Written by James V. Hart, Michael Goldenberg, Carl Sagan, and Ann Druyan

With Jodie Foster, Matthew McConaughey, James Woods, John Hurt, Tom Skerritt, Angela Bassett, and Rob Lowe.

Barry Sonnenfeld’s Men in Black and Robert Zemeckis’s Contact, both about the existence of extraterrestrials, are probably the first two blockbusters of the summer worthy of the name, even if many grains of salt are required to make much of a meal of either. I’m not claiming that Contact and Men in Black offer the only genuine chills and thrills around — I caught up with The Lost World: Jurassic Park a couple of weekends ago and enjoyed it more than its predecessor — only that they come closer to speaking my language. Given the preordained preeminence of Spielberg’s romp, I’m sure I would have slammed The Lost World, like most of my colleagues, if I’d seen it when they did. But that doesn’t mean it’s a bad movie — just that we all have an obligation to gripe when a pretty good genre piece is made to seem more important than a national election.

It could be said that Men in Black takes the National Enquirer approach to extraterrestrial life whereas Contact comes on like CNN, literally as well as figuratively. And though I don’t necessarily prefer the National Enquirer to CNN, my heart as well as my head favors Men in Black over Contact. Or, to put it a different way, because Men in Black ironically appropriates and thereby honors the tabloid print journalism that greets us at every checkout counter, it has more to say to us, even as lighthearted spoof, than the ponderous if sometimes exciting parable of Contact, which embraces with no trace of irony CNN and other TV staples as guarantees of actuality.

The two movies’ levels of aspiration only make this distinction more acute. Where Sonnenfeld is creating a buddy action adventure for boys, Zemeckis aims for a spiritual odyssey with a space-age, atheistic Joan of Arc heroine (Jodie Foster). But the romantic interest in each case implies a different story. Men in Black‘s Linda Fiorentino, as a plucky morgue pathologist cruised by Will Smith’s character, is an unstereotypical delight (and the best argument for a sequel), but Contact‘s Matthew McConaughey as a hunky New Age Billy Graham groomed for Saint Jodie is an embarrassing sop to believers and an outright hoot. Where Sonnenfeld is hip enough to see through his own poses, Zemeckis is so sincere and square — suffering after Forrest Gump from the usual case of post-Oscar piety — that at certain junctures he’s jumped feetfirst into unintentional camp. Both movies begin and end in outer space, and both make explicit equations between the microcosmic and the macrocosmic, but only Sonnenfeld manages to traverse this territory with the liberty of a free-floating bug. Zemeckis, for all the power of his storytelling and the urgency of his vision, ultimately becomes the prisoner of his own gravity.

I’m unfamiliar with the comic-book series on which Ed Solomon’s witty script for Men in Black is based, and I haven’t read the Carl Sagan novel, Contact, that was adapted for the screen first by the late Sagan (in collaboration with his wife, Ann Druyan), then by James V. Hart and Michael Goldenberg. But it’s obvious that the issue of mankind adapting to the existence of extraterrestrial life is seriously considered only in the novel and in Zemeckis’s movie. The premise of Men in Black — that about 1,500 aliens of various stripes and from various places currently inhabit the planet in human disguise, sometimes warring with one another, and that a secret government agency, Men in Black, is devoted to policing them — is the basis for a down-home satire about how we cope with cultural difference. (Among the disguised aliens identified on TV monitors are Sylvester Stallone and Newt Gingrich; if I were more TV-literate, I’m sure I’d have spotted many others.) One might conclude, then, that whereas Contact is primarily metaphysical and philosophical and only secondarily social, Men in Black inverts these priorities. But in fact the street-smart social satire of Men in Black has a purity that lends the film some philosophical weight, while Contact is so burdened with social, political, and religious issues that they infect and ultimately overwhelm much of the philosophical content.

A central image in Men in Black is the goo that issues from squashed, pulverized, or drooling insects — splattering a windshield in the opening gag and periodically drenching various characters thereafter, especially the heroes. (A typical exchange between agents: “Humanoid?” “You wish — bring a sponge.”) The working-class and ethnic sites associated with the aliens — a truck transporting illegal Mexicans, an exterminator’s van, and, in New York, a pawnbroker’s, a ghetto jewelry store, and an eastern European soup kitchen — reinforce the overall impression of funkiness. This funkiness is explicitly contrasted with the sleek anonymity of the Men in Black — Tommy Lee Jones as the wizened pro, Will Smith as a fresh recruit, and Rip Torn as the home-office manager — whose deliberate lack of emotional ties and distinguishing traits, such as fingerprints, is the natural correlate of their secret headquarters and high-tech equipment. A central tool, employed only by the wizened pro, is a pocket-size magic wand: the Neuralizer erases short-term memories and replaces them with posthypnotic suggestions. Allegorically, this nifty gadget implies a good deal not only about cultural consumption — the process by which we forget, say, last week’s summer blockbuster in order to make room for this week’s — but also about the self-imposed cultural amnesia of immigrants hoping to adjust to American life.

Since the Neuralizer is used by Jones on humans rather than on extraterrestrials, it doesn’t have a fixed allegorical function but rather poetically echoes the repressions and concealments of cultural differences and social ties that occur throughout the movie. Significantly, Smith has no visible past when we first meet him aside from being a New York cop — which makes the agency’s deletion of his identity seem redundant — and Jones’s only past outside the agency is his long-lost wife, who provides the film’s only noncomic moment, and a very poignant one. (As unlikely as it seems, I would nominate Tommy Lee Jones’s underplayed performance as possibly his best to date, rivaled only by his much showier role as Ty Cobb.)

A lot of reviewers have connected the heroes’ profession to Ghostbusters and their black suits to The Blues Brothers and Reservoir Dogs, but in fact these traits have more to do with the movie’s posters than with its flavor or vision. Much more important is its satirical notion that tabloid newspapers are our only reliable source of information — a fancy alluded to only twice but central to the script’s suave populist intelligence. (“Best investigative reporting on the planet,” the pro remarks to the recruit about a row of such papers at a newsstand. “You can read the New York Times. They get lucky sometimes.”) It reminds me of the hack journalist I once knew who wrote an astrology column — cynically concocted every week out of whole cloth — for one of these papers but who seriously read the astrology columns in a couple of other tabloids for advice about his future. The compulsion to believe in the improbable is surely as basic as the compulsion to believe in the probable, and the servicing of both compulsions by journalism implies a similarity and continuity between the two activities that we generally prefer to overlook.

By refusing to overlook it, Men in Black paradoxically respects the ordinary viewer in a way that few recent commercial movies do. The assumption of most summer blockbusters that their audiences are morons pollutes much of this year’s crop like a virus. But thanks to Solomon’s sparkling dialogue, Sonnenfeld’s graceful economy, and a steady visual inventiveness, Men in Black takes the radical step of assuming that its audience is hip and smart, and it shines with that generous act of complicity.

Some would call Robert Zemeckis a serious populist as well, but if he ever was one, that time has surely passed. By postulating stupidity as higher wisdom and reducing American history to a history of American TV, Forrest Gump qualifies as fake populism from beginning to end. And though Contact strikes me as a more honorable (if less effective) effort — passionately extolling the virtues of scientific exploration — the specter of Gump still hangs over this movie, which likewise sees the media as the bedrock of our shared reality. Even the opening sequence implies a mystical association of the cosmos with media history: this striking whirlwind tour of interplanetary space is accompanied by radio evocations of everything from rock to Walter Winchell. It winds up in the eye of Ellie Arroway, a little girl in Wisconsin speaking over her shortwave radio to Pensacola, then asking her beloved father if they can talk to Saturn and her dead mother as well. Soon afterward she also loses her father, and her quest for origins is fully in place.

Ellie grows up to become Jodie Foster, a dedicated/fanatical radio astronomer in search of funding as well as father figures. Among the latter are a treasured colleague (William Fichtner) who helps her transmit and receive radio signals and whose name, Kent Clark, irrelevantly suggests an inverted Superman; a bad father (read: villain) and former mentor (Tom Skerritt) who briefly becomes her boss, then her competitor, and who kowtows shamelessly to the power structure; a religious scholar named Palmer Joss (Matthew McConaughey) who gives her a Cracker Jack compass, virtually repeats her father’s tag line (“If there wasn’t anyone else out there [in the cosmos], it’d be an awful waste of space”), and goes to bed with her; and an eccentric billionaire (John Hurt) who lives on a well-appointed plane (recalling Jules Verne’s Captain Nemo) and comes up with the funding.

Four years into Ellie’s newly financed research, an intricate radio message comes from the distant star Vega, and Bill Clinton holds a press conference — the first of several Clinton appearances in the movie, all of which elicited embarrassed titters at the preview screening I attended. Whether these appearances were achieved through morphing, manipulating found footage, or both, the effect is virtually identical to that produced by TV personalities like Bernard Shaw, Larry King, and Jay Leno, who agreed to perform in the movie. (Each of these three appears in the final cast list “as himself,” but unless I missed something, Clinton isn’t accorded the same billing.) The eeriest aspect of Clinton’s presence is that, deliberately or not, he winds up here as the virtual reincarnation of Forrest Gump — an “aw, shucks” type magically sharing space with a movie star like James Woods (another kowtowing villain), just as Tom Hanks playing Gump once shared space with Lyndon Johnson.

But the movie’s CNN strategy, whereby credibility is measured in TV exposure, proves fatal, often throwing the proceedings into a laughable tailspin: Zemeckis doesn’t seem to realize that by using Clinton, Shaw, King, Leno, and others to validate his fiction, he’s kowtowing to the power structure just as shamelessly as the movie’s villains. CNN could be called the TV equivalent of the New York Times in terms of prestige, and this is a movie that hankers after prestige as much as Ellie Arroway hankers after the secrets of the universe. Zemeckis is clearly going for broke here, with his liberal borrowings from the “trip” sequence in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 and from the patriarchal sentimentality of Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind and E.T., not to mention his over-the-top use of McConaughey. But he’s periodically landing in high camp: the sentiments may be humanist, but the aesthetics are strictly Ayn Rand. Aiming hysterically for some kind of consensus filmmaking — presumably in order to court the constituency that gave him his Gump Oscar — he can only demonstrate, much as Clinton has, that you can’t try to please everybody on every issue without eventually looking like a bit of a hypocrite and fool.

Zemeckis started out as a Mad-style satirist, and it’s possible that he’s trying to recapture some of that impulse in the various media circuses of Contact. But if he is, that strain doesn’t wash with all the heavy-duty high seriousness. Sonnenfeld is able to bracket Jones’s longing for his absent wife in Men in Black as an isolated somber moment without skipping a beat, but Zemeckis can’t engineer the same sort of flip-flops without the strategy boomeranging out of control. Even Foster’s performance, good as it is, skirts self-parody when it recalls some of her other pictures (The Accused, The Silence of the Lambs, Nell) by positing her as some kind of middlebrow authentication of earnest female self-empowerment. (Even so, she fares much better as a role model than Angela Bassett, who’s less a character here than a form of demographic appeasement.) The clearest stretch of Zemeckis satire in Contact — a survey of the crackpot carnival that’s gathered around the earthlings’ construction of a Vega-designed spacecraft — is on all counts the weakest, both as an unimaginative rip-off of Billy Wilder’s Ace in the Hole and as a belaboring of the obvious.

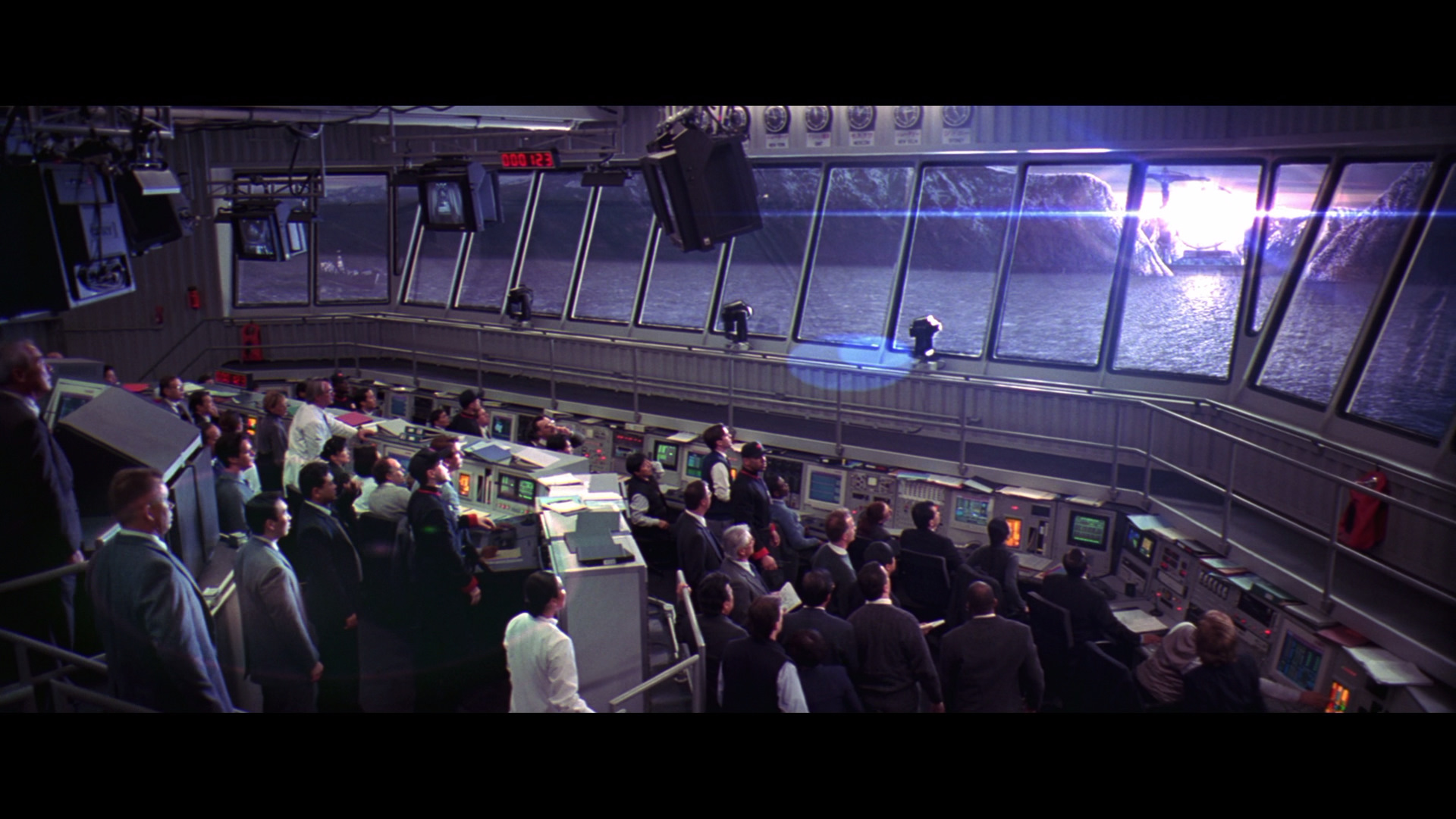

This doesn’t mean that Contact absolutely capsizes. The alien spacecraft itself superbly combines speculative design and sheer folly, recalling some of the best moments in Metropolis and Things to Come, and some of the high-tech human equipment is almost as much fun. The space journey itself may culminate in a vision of paradise that’s strictly southern California, but there are plenty of excitements along the way and a fair number of entertaining ambiguities to mull over afterward (not all of them plausible). And though Contact is at least an hour longer than Men in Black, Zemeckis tells a skillful, streamlined story right to the end.

But when it comes to contemplating the implications of mankind not being alone in the universe, he’s clearly bitten off a lot more than he can chew. I’d recommend Olaf Stapledon’s 1937 novel Star Maker instead: it tackles the same theme with simultaneous modesty and majesty, throwing in a stirring account of the creation of the universe as a bonus, bountifully extending ideas that this movie barely begins to sketch. It isn’t much of a page-turner but it’s a formidable mind-expander; at the very least it doesn’t scramble for celebrity endorsements — the Forrest Gump Seal of Approval — while trying to explain the cosmos.