This was written in the summer of 2000 for a coffee-table book edited by Geoff Andrew that was published the following year, Film: The Critics’ Choice (New York: Billboard Books). — J.R.

Apart from his scandalous Salò, or the 120 days of Sodom, 1975 -– another film with spiritually induced levitation -– this shocking 1968 feature, Pier Paolo Pasolini’s last film with a contemporary setting, may be his most controversial work, displaying the kind of audacity and excesses that send some audiences into gales of defensive, self-protective laughter. (For a contemporary near-equivalent, think of Bruno Dumont’s 1999 film L’Humanité.)

The “theorem” of the title is a mythological figure whose arrival is heralded by Pasolini’s favorite fetish-actor, Ninetto Davoli, bringing a telegram to the home of an industrialist (Massimo Girotti). An attractive young man in tight-fitting trousers (Terence Stamp) then pays an extended visit, proceeding with solicitous devotion to seduce every member of the household — father, mother (Silvana Mangano), teenage daughter (Anne Wiazemsky), somewhat older son (Andrès José Crux), and maid (Laura Betti) — to the recurring strains of Mozart’s Requiem Mass and a modernist score by Ennio Morricone.

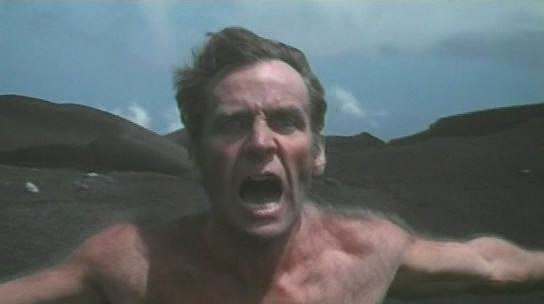

Then the stranger leaves as mysteriously as he came, and everyone in the household undergoes cataclysmic and traumatic changes. The provincial maid, whom he saved from suicide, returns to her village, meditates, and eventually levitates. The daughter goes into a catatonic trance, the mother begins to pick up young men on the street, and the son retreats to his room and paints in a wild, chaotic fashion that includes urinating on one of his canvases. The father not only gives away his factory to its workers but takes off all his clothes in the middle of Milan’s Central Station and is later seen trekking across a desert, howling like a wounded animal. Pasolini may have been as much in conflict with his own divided nature as any of his characters.

Almost everyone rejected Teorema in 1968, and it has not necessarily grown any more acceptable in the intervening years — even if Pasolini’s status as one of the key Italian poets of the 20th century remains intact. If anything, what Stuart Hood (who translated Pasolini’s novel) suggests may be “Pauline misogyny that informs Pasolini’s attitude towards his women characters” and what film theorist Richard Dyer describes as “the association of gay sex with humiliation” makes Teorema even more politically unacceptable today than it was three decades ago.

While he was making this film, Pasolini wrote a parallel novel of the same title, part of it in verse; neither work is strictly speaking an adaptation of the other but a recasting of the same elements, and the stark, utterly sincere poetry of both is like a triple-distilled version of Pasolini’s personal view of the world — a view in which Marxism (as opposed to communism), Christianity (as opposed to the Catholic church), and homosexuality are forced into mutual and scandalous confrontations. The style is eclectic but never dilettantish. To emphasize the importance of Stamp’s arrival — seen in Old rather than New Testament terms, with a citation from the book of Exodus — the film begins silently and in black and white, moving to sound when Davoli appears, then to color with the entrance of Stamp.