This was written in the summer of 2000 for a coffee-table book edited by Geoff Andrew that was published the following year, Film: The Critics’ Choice (New York: Billboard Books). — J.R.

Considering how romantic it is, how sad and funny and charming, it is a sobering fact that François Truffaut’s second feature –- and the first one that qualifies as a quintessential New Wave expression — was a disaster at the boxoffice. Indeed, if this eccentric adaptation of David Goddis’s 1956 crime novel Down There illustrated any general commercial principle, this may be that one subverts overall genre expectations at one’s peril. For Tirez sur le pianiste is a film noir that literally turns white (through such images as piano keys or a snowy hillside) when the plot is at its darkest, and one that sometimes interrupts the viewer’s laughter with a disquieting catch in the throat.

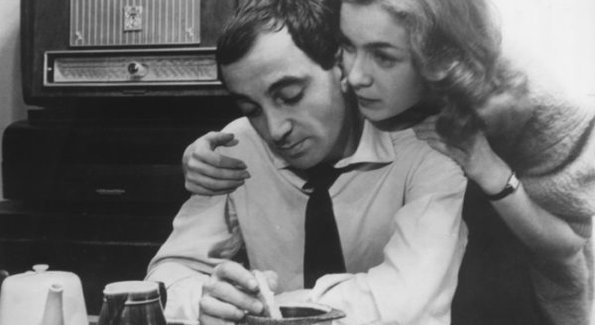

The opening sequence already sends out bewildering crossed signals. A man fleeing in panic through dark city streets at night collides with a streetlight, then finds himself talking quite calmly with a sympathetic stranger –- a character who exits the movie immediately thereafter -– about the latter’s love for his wife. Moreover, while the fluid and flexible black-and-white cinematography (by Raoul Coutard) is in the anamorphic process Dyaliscope, the ambience is cramped and cozy in the best low-budget tradition. It turns out that the man, named Chico Saroyan (Albert Rémy), is looking for his long-lost brother Edouard (Charles Aznavour), a former concert pianist now playing folksy ragtime in a dive under an alias, Charlie Kohler — although it takes us awhile to discover why, in an extended flashback. (Aznavour, a crooner who became famous after this film was made, does not sing a note, although as Edouard he periodically delivers a kind of stream-of-consciousness voiceover.)

The film recounts at least two tragic love stories that result in Edouard’s retreat, and the camera participates in the action almost as fully as the characters. It circles the bedroom of a barmaid (Marie Dubois) while she and Edouard make love in superimposition, follows a mysterious young woman with a violin case out of a rehearsal room while his piano thunders offscreen, and later carries us in stages all the way from city to country and into snowy weather from the front seat of a car.

A study of a shy man who periodically hides behind his music, this film was a shift for Truffaut after his autobiographical The 400 Blows (1959), but was arguably just as personal. Although the earlier film’s treatment of children is often said to bear the influence of Jean Vigo’s Zéro de conduite (1933), Shoot the Piano Player has a comic sequence with a gangster in a car boasting about his possessions to a kidnapped boy -– another of Edouard’s brothers -– that seems inspired directly by Zéro’s opening sequence on a train. And when the hood swears his mother will drop dead if he isn’t telling the truth, Truffaut cuts abruptly to a silent-movie image of the mother doing precisely that — a characteristic signal that this picture might do anything if it takes the director’s fancy. We experience this less as indulgence than as Truffaut generously sharing his delight in making movies.