The following was written at some point in the early 1980s, as a kind of postscript or pendant to my first book, the autobiographical Moving Places: A Life at the Movies (New York: Harper & Row, 1980; 2nd ed., Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995). I was living in Hoboken at the time, and secretly in love with another writer whose first name was Veronica. A slightly altered and doctored version of this piece eventually turned up in Ian Breakwell and Paul Hammond’s English anthology Seeing in the Dark: A Compendium of Cinemagoing (London: Serpant’s Tail, 1990). The version here has also been altered and doctored a little, and I’ve added all the photos, including those of the Ritz before and after its 1985 restoration. — J.R.

Putting Back the Ritz

Jonathan Rosenbaum

Between about 1947 and 1951, when the Ritz Theater in Sheffield, Alabama was still open (it was built in 1928 and received an Art Deco upgrade for talkies about five years later), my main encounters with the place, between the ages of four and eight, were on trips with my father across the river to pick up the final reports on the daily receipts on all four of the Rosenbaum theaters our family owned in Sheffield and Tuscumbia. (There were three more theaters in Florence at the end of his route, and two more in Athens, where he drove twice a month.) As soon as we left Florence and crossed the Tennessee River we passed from Lauderdale, a dry county, to Colbert, a wet one, and the difference was plainly visible: a sudden array of beer stands and gaudy neon nightclubs flickering past made Sheffield a sort of Baghdad next to the more prim outposts of Florence, the birthplace of W.C. Handy and a bastion of respectability. Sheffield was the smaller town, but it had a bigger train station, more industrial soot, more prostitutes, and an all-black movie house, the Carver, all in close proximity to one another. Across the tracks was Jack’s Chicken Shack, a Negro hangout that sold bootleg liquor after the county went dry around 1952, and Sheffield began to grow more ashen and dusty, shriveling into a near semblance of a ghost town.

Today the town shows some signs of coming back to life. Colbert went wet again in 1982, there’s an active local theater group, and some people in the area are in the process of restoring and reopening the Ritz — which had survived mainly as a warehouse, and briefly as a recording studio in 1957 — to put on plays. It hasn’t shown a movie for over thirty years, but the pink seashell murals, the stage, and the “white” and “colored” balconies are still intact, fossils of another culture.

My father’s nightly trips across the river five times a week were usually to the Colbert in Sheffield (built around the time of Pearl Harbor, half a block from the Ritz, and today a parking lot) and the Tuscumbian (built in 1950, a block from the Strand, and today part of a bank). But if the daily figures hadn’t yet been brought over from the Ritz and Strand, we would stop off there too. Sometimes my brothers and I were allowed to get out of the car with him and peek at the movie in progress while he spoke to the manager or cashier. In a way this functioned for us like window shopping: a random five-minute slice of a feature would enable us to decide whether to see the whole thing at the Shoals, Princess, or Majestic in Florence, when it resurfaced there.

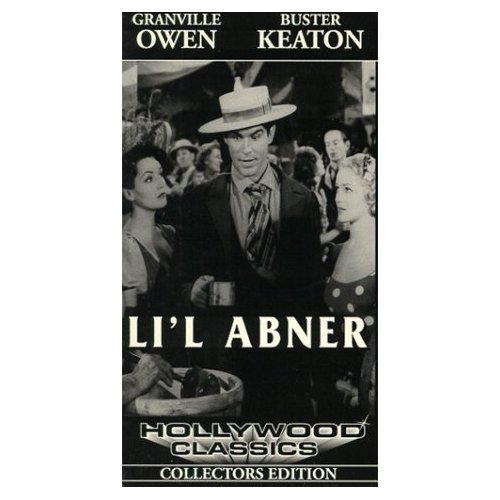

But sometimes a double bill would show at the Ritz and nowhere else. One such occasion was Labor Day 1949, when my parents went off on a holiday barbecue or picnic and deposited the three oldest boys — David (eight), Jonny (six), and Alvin (four) — with a teenage black babysitter named Earl at the Ritz to see Li’l Abner (the early black and white version, with Buster Keaton in a small part) and I Married a Witch. It was Alvin’s first time at the movies, but the other two of us were seasoned veterans by this time. Jim Crow laws dictated that we all sit up in the colored balcony, so we followed Earl up the stairs of the separate entrance, located to the right of the box office, and found ourselves in the highest tier of the auditorium. Down below were the pink seashell murals lit by fluorescent lights, and distant black and white movies on the screen. Li’l Abner — without the color of the comic strip in the Sunday paper — seemed bogus, and bogus hillbilly at that, but David and Earl, both schooled in the macho preference for raucous art, liked nothing better than a bogus barnyard. For Alvin and me, bogus mansions and graveyards were the thing, and I Married a Witch a sweeter brew.

The principal moment I’m left with is a shot of two smoky essences in bottles, the sound of dry autumn leaves rustling through a chill night wind, and the voices of Cecil Kellaway and Veronica Lake, father and daughter, conversing from their adjacent bottles. Most of this has to do with Veronica Lake’s deep, husky voice: a smoky spirit whose name and form collectively conjured up a feminine aura of water, vapor, air, smoke, and flesh at the same time — a floating dreamboat that any boy of six would be proud to be married to. Having just seen Topper at the Princess the week before, I had all I needed to complete my erotic evaporation fantasies and crawl into the diaphanous lap of Lady Veronica. Indeed, by the time the credits of René Clair’s supernatural comedy came on, the ads had already done their work, and I was already invisibly inside her bottle too, ready to share in her throaty vibrato.