From the Chicago Reader (October 18, 2002). — J.R.

In Praise of Love

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed and written by Jean-Luc Godard

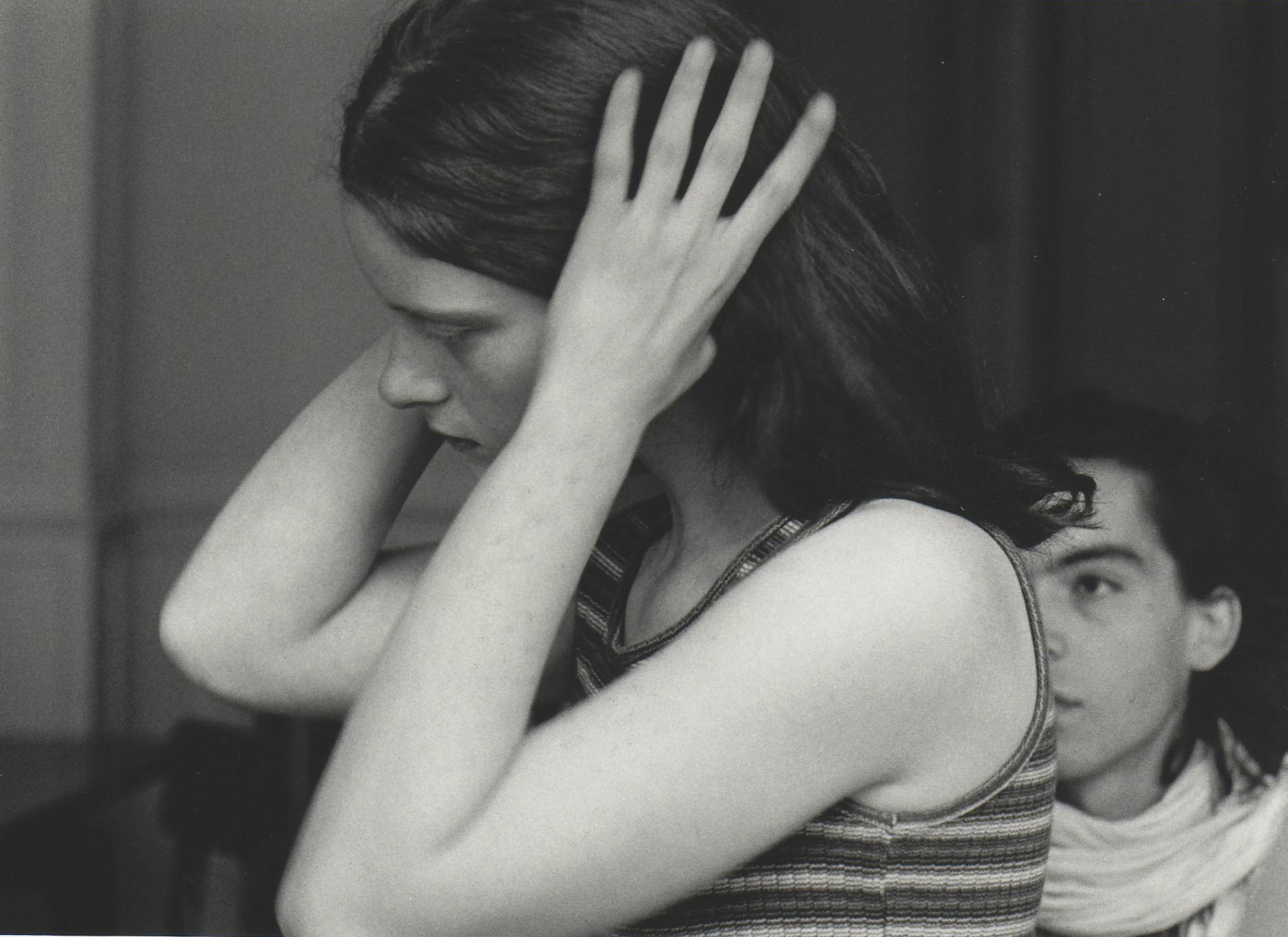

With Bruno Putzulu, Cecile Camp, Claude Baignieres, Remo Forlani, Audrey Klebaner, Mark Hunter, and Jeremy Lippmann.

Berthe: “When did the gaze collapse?”

Edgar: “Before TV took precedence.”

Berthe: “Took precedence over what? Current events?”

Edgar: “Over life.”

Berthe: “Yes. I feel our gaze has become a program under control. Subsidized….The image, monsieur, the only thing capable of denying nothingness, is also the gaze of nothingness on us.”

— In Praise of Love

Let feelings bring about events, not the contrary. — Robert Bresson, Notes on Cinematography, quoted in In Praise of Love

Six years ago, when Jean-Luc Godard was presenting his feature For Ever Mozart in Toronto, he described Eloge de l’amour (In Praise of Love) as his next project — a play he would stage in Switzerland. So it seems appropriate that his film with the same title opens with a young man, Edgar, planning a project called Eloge de l’amour that might be a film, a play, a novel, or an opera. (During the first hour of the film only two intertitles are used: “something” and “about love.”)

Eloge de l’amour translates literally as “eulogy of love,” but the funereal tone of the film might make “elegy” — “a song or poem expressing sorrow or lamentation, especially for one who is dead” — seem closer to the mark at first. The setting is Paris, and the stunning cinematography is in black and white, with some of the blackest nocturnal blacks imaginable. Once again, Godard is reflecting on his own practice as a filmmaker, though this time his personal investment in the material seems deeper than it was in For Ever Mozart and Helas pour moi (1991), and closer to the feeling of Nouvelle vague (1990), his best late feature before this one.

Edgar’s project involves three couples (young, “adult,” and old) and four “moments” of love (meeting, physical passion, separation, and reconciliation), and he begins by interviewing prospective members of the three couples. Yet the first two-thirds of the 94-minute film has less to do with love per se than with the lives of members of the French resistance during World War II and of poor and homeless Parisians in the present. Eventually we discover that Berthe — a young woman Edgar met in Brittany two years earlier and particularly wants to include in his project, though she shows no interest in participating — has killed herself.

In the film’s final section — set two years earlier and shot in video with floridly oversaturated colors — the themes of love and the French resistance finally become intertwined. Edgar arrives in Brittany to interview a historian, Jean Lacouture, about Catholics in the resistance, saying he’s “composing a cantata for Simone Weil.” This leads to his meeting an elderly couple, friends of Lacouture who fought in the resistance and have been together ever since — even though the man, following the orders of his superiors, exposed the woman as a member of the underground during the war. The two are now negotiating with a representative of the American embassy in Paris to sell their story to a Hollywood studio, for a feature to be directed by Steven Spielberg and written by William Styron and to star Juliette Binoche (who’s just won an Oscar for her part in The English Patient). The couple’s granddaughter, a legal trainee who advises them on the contract, is Berthe, the woman who will kill herself two years later.

I’ve now seen this feature, opening this week at the Music Box, several times. But it wasn’t until I recently bought the film on DVD — in England, to my knowledge the only country where it’s available in that form — that its pieces began to fall into place. Maybe this is because Godard — the filmmaker who demonstrates most concretely that films can speak to us as literature does — becomes more accessible the more one roams around in his films, just as one does in books. Or maybe it’s because seeing the film so many times on the big screen primed me for seeing it on DVD.

Some friends have fallen in love with this masterpiece on first viewing; others will probably never find it bearable, no matter how many times they see it. (Dutch critic Dana Linssen, who was just in town to serve on the Chicago International Film Festival’s FIPRESCI jury, told me she’d always avoided Godard’s work, a reaction to her parents’ enthusiasm; but this film led her to see every other Godard film she could find.) I do think seeing it in different venues is invaluable, and I encourage viewers to seek out alternatives, which are sometimes more available than you might guess. (Adventurous consumers might be glad to know, for example, that English-subtitled DVDs of Abbas Kiarostami’s The Wind Will Carry Us just came out in both the U.S. and France; the French version, which costs a little less, gives you an additional disc with two fascinating feature-length documentaries about the making of the film.)

“No other filmmaker has so consistently made me feel like a stupid ass,” Manny Farber wrote of Godard 34 years ago. Today Godard is just as intimidating. I’m gratified that I caught some film references in In Praise of Love. The final line of dialogue in Robert Bresson’s Pickpocket is cited by a man standing in line at a movie theater, who happens to be film critic Noel Simsolo. Another scene contains an admiring allusion to Samira Makhmalbaf’s The Apple (the French poster for it is visible). There are also variants of lines from Roberto Rossellini (“Things are there. Why invent them?”) and from John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (“When the fact becomes legend, print the legend”), as well as a couple of songs from Jean Vigo’s L’Atalante, nostalgically heard while a man and woman converse by the Seine. But I’m generally clueless when it comes to the literary quotations. The authors of a seemingly random ten of them are listed in the final credits, and though I recognize half of the names, I can’t connect them to particular lines of dialogue. But I’m sure I’m not meant to. The trick when watching Godard is to catch the pitch of his poetics, savor the pleasure of his sounds and images, and ponder the historical, philosophical, and ethical issues that intersect with them. Catching specific references is at best a minor sport; much more important is catching the beauty of the argument as it sails past in diverse forms. (“Every thought should recall the debris of a smile” is one relevant remark.)

Some critics of this film seem bewildered by Godard, and their response can be skeptical or angry: last month Anthony Lane concluded, in a kind of delirium of chic New Yorker entitlement, “Godard has never been a thinker,” which is like saying Fred Astaire didn’t know his left foot from his right. Yet Godard’s films can confuse even his admirers. Reviewing In Praise of Love in Sight and Sound last November, Keith Reader wrote that the years of the resistance are “almost the only period of recent French history Godard has not [previously] alluded to in his work” — overlooking their central role in Godard’s magnum opus, Histoire(s) du cinema. Godard, born in 1930, was an adolescent during the occupation, the same period when he was discovering cinema, which undoubtedly helps to explain the connection. That connection is also evident in In Praise of Love, which is largely a recasting in fictional terms of the essayistic reflections on history found in Histoire(s) du cinema.

Most viewers tend to feel inadequate when watching Godard films. His methods of telling a story — often separating sound from image and plot from dialogue — always require readjustments on the viewer’s part. An even more crucial barrier in this film is the melancholy tone that admits no humor, though humor is often a saving grace in his more ponderous work; this film has some of the same Germanic heaviness that his 1994 JLG/JLG does. “He likes dead people more than living people now,” a French magazine editor told me last year after seeing In Praise of Love, and for months afterward I cited this remark whenever I had to explain why I couldn’t accept the film wholeheartedly. But I now think this observation is misguided, for Godard is struggling with the fact of his own aging (he turns 72 in December) and trying to be candid about that struggle. One consequence is that the actors he opts for here, as he did in the much less successful For Ever Mozart, are real people, not movie stars. When one interviewer asked, “What did you look for in the actors?” he replied, “Something, perhaps not much, that was real.” He hasn’t lost sight of beauty or emotion, but he wants to achieve them the hard and honest way — without Hollywood subterfuge. The film is virtually framed by two monologues by old women devoid of glamour speaking directly to the camera, and both have an uncommon beauty that can be perceived only after we get past the shock of their directness.

Then there’s the question of the film’s anti-Americanism, which has been widely criticized and resented in this country. Yet Godard’s criticism of American arrogance and domination is less monolithic than, for instance, the U.S. State Department’s current distrust of Muslims or its indifference to the opinions of Baghdad’s citizens. And Godard respectfully invites an American journalist, Mark Hunter, to speak in the film about what he’s witnessed in Kosovo.

When this film opened at Cannes last year some American critics were also offended by Berthe’s anti- Spielberg remark “Mrs. Schindler was never paid; she’s in poverty in Argentina.” They responded that Spielberg had, after all, given money to Holocaust research. But Thomas Keneally’s nonfiction book that Schindler’s List is derived from makes it clear that Emilie Schindler played a substantial role in saving Jewish lives in Moravia, for which Spielberg’s film gives her virtually no credit.

Most of the rest of Godard’s anti-American brief in the film plays as follows: “Americans have no real past….They have no real memory of their own. Their machines do, but they have none personally. So they buy the past of others, especially those who resisted. Or they sell talking images. But images never talk.” It’s a sweeping indictment, justifiable perhaps when directed at Disneyland, but absurd when it encompasses such examples of American self-scrutiny as The Education of Henry Adams and The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

Still, it’s worth noting the poetic role this analysis of image appropriation plays in Godard’s film, especially in relation to the film’s skepticism about adulthood. We’re repeatedly told that young and old people recognize one another immediately, “but with adults, nothing is obvious” — because people tend to pass from youth to old age without achieving adulthood in between. And it’s implied throughout Godard’s analysis in this film and Histoire(s) du cinema that the history of both America and cinema can be read the same way: each began as a kind of promise, a source of hope, but each then passed from innocence to senility without achieving maturity at the time it was most needed, during World War II. Thus the failure of cinema to deal adequately with the Holocaust and the resistance becomes matched by the failure of American cinema, with its stranglehold on global images, to deal adequately with the same material. And the result is that Emilie Schindler’s heroism can be excluded from Schindler’s List, and Spielberg’s feel-good image of Jews being saved from the gas ovens can replace the less palatable image of the Jews who perished in them. That’s showbiz, one might say. Unfortunately the American film industry identifies cinema with showbiz to the exclusion of practically everything else.

As J. Hoberman recently pointed out in the Village Voice, In Praise of Love‘s use of color and black and white is deliberately conceived to invert Spielberg’s priorities in confronting the historical past — Godard’s black-and-white sequences represent the present (even as they recall the black and white of his early-60s features), and color video represents the past. Godard’s eulogy for both periods is above all an expression of respect for the truth that lies beyond the more comforting, more palatable images we manufacture. It’s a eulogy given more in sorrow than in anger as he looks without blinking at the wreckage of the contemporary world, but it also glows with the recollection of a smile.