This essay, published in Film Comment in September-October 1976, represented one particular round in a series of initiatives and polemical forays I conducted on behalf of Jacques Rivette’s Duelle, which included getting it into the Edinburgh International Film Festival that year (and then writing about that festival at length in the Winter 1976/77 issue of Sight and Sound). One part of my effort was to engage the attention and interest of writers associated with the English theoretical magazine Screen, and this portion of the effort mainly failed: the principal response of the Screen writers who bothered to see it, as I recall in terms of their comments to me, was that it was basically warmed-over Cocteau and/or Franju — a reaction that I consider now, as I did then, to be rather obtuse and philistine. On the other hand, I no longer relish Duelle with quite the same fervor that I did at the time, even though there are certain moments in Jim Jarmusch’s very pleasurable The Limits of Control, that remind me of it. (Nowadays I prefer L’amour fou, both versions of Out 1, and Celine and Julie Go Boating — for me the peaks of Rivette’s work.) Read more

This appeared in The Soho News on March 11, 1981. A month earlier, I had launched a kind of weekly column there called “Declarations of Independents” that was in diary form — a bit like some of my Paris Journals and London Journals for Film Comment during the 70s –- and this was the third of these. — J.R.

Feb. 24: Why go all the way to the Thalia tonight to see five Screen Directors Playhouse episodes, all half-hour TV shows from the mid-50s? Two professional reasons spring to mind, both essentially recycling operations. As often happens in such cases, I feel myself split between the two — processes that honor my asocial aesthetics on the one hand, my social politics on the other.

Auteurist Retrieval technology (we’ll call it ART for short) — cultivated by me and a lot of other film freaks in the late 60s — is predicated on the pleasure of recognizing the taletale signs of favorite directors in all sorts of unlikely material. And what better excuse to put ART to work than patriarchal episodes by John Ford, Leo McCarey, Frank Borzage, Tay Garnett, and William Seiter? Indeed, to narrow the focus down to the evening’s main event, what better specimen could one hope to find but a crisp 35mm print of Ford’s Rookie of the Year, made immediately before his masterpiece The Searchers, with the same scriptwriter (Frank Nugent) and no less than four of the same actors — John Wayne, Pat Wayne, Vera Miles and Ward Bond — playing central roles? Read more

This review, from the February 4, 1981 issue of The Soho News, is most likely harsher than it needed to be. Since Mary McCarthy’s death, I’ve been moved to reformulate some of my positions about her after reading the wonderful book Between Friends: The Correspondence of Hannah Arendt and Mary McCarthy 1949-1975 (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1995) edited by Carol Brightman, which reveals a side of McCarthy that seems quite contrary to her much better-known bitchiness as a critic. It proves to me that unforeseen and unforeseeable sides of some people tend to come out only in specific relationships with certain other people, and the loving generosity of McCarthy’s letters to Arendt are a particular striking example of this. —J.R.

McCarthy’s Law

Ideas and the Novel

By Mary McCarthy

Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, $7.95

Despite her wicked way with some words and ideas, Mary McCarthy has never exactly thrilled me with her aesthetics. With a taste stuck so comfortably, nostalgically, even trivially in the prosaic 19th century that even the avant-garde that she values often seems furnished with fog and brass doorknobs à la Doyle, Verne, or Poe, her acute critical intelligence usually whiles away its time polishing statues and suits of armor — rather like the New York Times Book Review — whenever she turns to the Novel. Read more

My first meeting with Samuel Fuller is chronicled in this interview/essay published in the July 9, 1980 issue of The Soho News and was reprinted in my recent collection Cinematic Encounters: Interviews and Dialogues. Seven years later, while concluding my academic career at the University of California, Santa Barbara, where I was placed in charge of running the film studies summer school program, I was still crazy about Fuller, and invited him to serve as our “visiting artist”, which led to our becoming friends from that summer until his death a decade later. I did my best to try to capture his singular way of talking in this article. For my title, I’m using the headline on that issue’s front page, not the title given inside (“Sam Fuller Reshoots the War”). — J.R.

When I enter his suite at the plaza, he’s finishing lunch, expressing his regret about missing Godard at Cannes, remarking on the absurdity of prizes at film festivals, asking me what Soho News and Soho are. (The one he knows about is in London — he fondly recalls a cigar store on Frith Street.)

It isn’t hard to figure out why Mark Hamill affectionately calls him Yosemite Sam, or why Lee Marvin simply says he’s D.W. Read more

This was originally published in the July 1976 issue of the Monthly Film Bulletin (vol. 43, no. 510), to coincide with the release of Hitchcock’s Family Plot (illustrated on the cover, and reviewed in that issue by the editor, Richard Combs). — J.R.

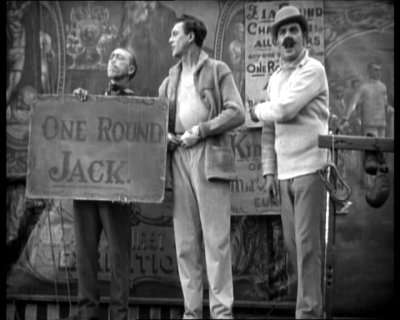

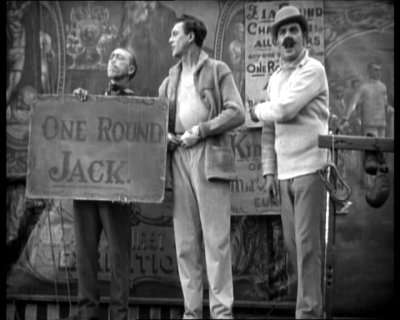

Ring, The

Great Britain, 1927

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Dist—BFI. p.c–British International Pictures. p–John Maxwell. asst. d—Frank Mills. story/sc—Alfred Hitchcock. continuity—Alma Reville. ph—John J. Cox. a.d—Wilfred Arnold. l.p—Carl Brisson (“One Round” Jack Sander), Lillian Hall-Davies (Nelly), Ian Hunter (Bob Corby), Forrester Harvey (Harry), Harry Terry (Barker), Gordon Harker (Trainer), Billy Wells (Boxer). 3,179 ft. (at 16 f.p.s.) 132 min. (16mm). Original 35 mm footage—8,400 ft.

At a traveling circus, prizefighter “One Round” Jack Sander is knocked out and defeated for the first time in his show by Bob Corby, an Australian heavyweight, and a mutual attraction develops between the latter and Nelly, Jack’s ticket-seller fiancée. With his prize money, Bob buys Nelly an arm bracelet which she hides from Jack, and Bob’s manager offers Jack the chance of a job as the champion’s sparring partner if he wins a trial match, which he grudgingly accepts. Read more

“Michael Jackson’s unforgettable memorial proved a moving high point in a saga that has captivated the world,” reads a headline in the July 17 issue of Entertainment Weekly. Since that’s (unsurprisingly) their lead story, this must mean that the Jackson memorial, whatever and whenever it was, must have qualified as entertainment — and that anyone and everyone who wasn’t captivated and entertained by it doesn’t belong to the world.

An interesting and highly diverse demographic — including, among others, me and my best friends, all the members of the Taliban, and, I presume, most of the people in China. I wonder if we could start a new religion based on this common ground. [7/11/09] Read more

An extraordinary piece of chicanery by Kelefa Sanneh entitled “Discriminating Tastes” heads off the Talk of the Town section in the current (August 10 & 17) issue of The New Yorker. The subject is the alleged “reverse racism” or “anti-white” bias of President Obama, as kicked off by his controversial offhand remark last month that a policeman who arrested a man in his own home “acted stupidly”. This was later described by Fox News‘s terminally stupid Glenn Beck as a revealing exposure of Obama’s “deep-seated hatred for white people.”

Not even once in this article does Sanneh bother to mention or even acknowledge the fact that Beck and so many other commentators are so eager to suppress and/or obfuscate — that Obama is half-white. As far as this article (and, it would appear, an alarming amount of other American punditry) is concerned, Obama is simply and unambiguously (and irrevocably) “a black President,” not someone who was born to a white mother and a black father. So in other words, according to this peculiar argument, Obama harbors a “deep-seated hatred” not only for his late mother but for half of himself — although this latter portion of the equation is almost never brought up. Read more

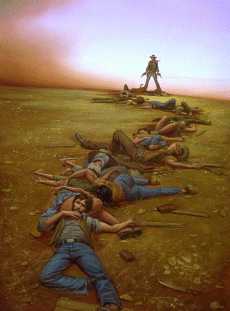

It seems significant that a good many defenders of Inglourious Basterds that I’ve been reading happily buy into the popular myth that scalping is basically something that indigenous Americans did, full stop. It seems that we non-indigenous Americans are still in almost complete denial about our own heritage of genocide in North and South America, which came much closer to succeeding than even the Nazi efforts with the Jews did — an estimated 70 million victims. I assume that some of the indigenous Americans who are still around must be aware of this obscene misrepresentation, but why should we care what they think?

Anyway, here’s some useful information gleaned from the Internet:

Euro-American traditions of scalping

Scalping: Fact & Fantasy

—By Philip Martin

Stereotypes are absorbed from popular literature, folklore, and misinformation. For instance, many children (and adults) incorrectly believe that fierce native warriors were universally fond of scalping early white settlers and soldiers. In fact, when it came to the bizarre practice of scalping, Europeans were the ones who encouraged and carried out much of the scalping that went on in the history of white/native relations in America. Read more

Christian Keathley is currently writing a book about Otto Preminger. I don’t know whether this lucid theoretical essay, centered around a textual analysis of an early scene in Preminger’s Whirlpool (1949) — which appeared in the second issue of World Picture Journal last fall, and which I’ve just discovered (following a Paul Fileri lead in the new Film Comment) — will form part of this book. But it does suggest that Keathley will have plenty to say on the subject of Preminger.

Consider, just for starters, the end of his fifth paragraph, before he even gets around to Whirlpool:

The social issues under interrogation in Preminger’s films were not subtextual — they were the manifest content. Indeed, to point out that there is a subtext of incest in Anatomy of a Murder, Bonjour Tristesse, and Bunny Lake is Missing is merely to state the obvious. As a result, since the early 1970s, Preminger has been a severely under-examined filmmaker.

And when Keathley analyzes the sequence from Whirlpool, charting the dialogue and gestures between a kleptomaniac (Gene Tierney) and her psychiatrist husband (Richard Conte), he has more to say about Preminger’s mise en scène and its power than just about anyone I’ve read on the subject. Read more

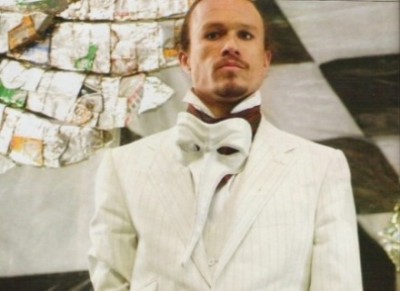

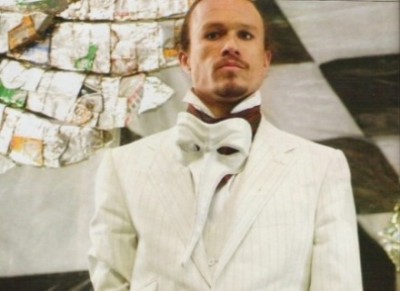

Thanks to John Iltis, the estimable dean of Chicago film publicists, here is a link to a rather eye-opening piece from a few days ago by the London Telegraph‘s Sukhdev Sandhu about changes in Anglo-American film culture over the past decade. Some of the thoughts here seem to corroborate a few of my own recent observations about respective differences — a widening rift, really — in the reception and perception of both Fantastic Mr. Fox and The Imaginarium of Dr. Parnassus in the U.K. and the U.S. (in the latter case in particular, the cross-referencing of Heath Ledger’s character with Tony Blair). –J.R. Read more

This book review was the first thing I ever wrote for The Soho News, a small-time weekly competitor of The Village Voice that I wrote for every week for about a year and a half (1980-81), reviewing books as well as movies on a fairly regular basis. I did 68 pieces for them in all, and this first effort, as I recall, was a kind of trial balloon. — J.R.

The Greening of Switzerland

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

——————————————————-

Doctor Fischer of Geneva or the Bomb Party

By Graham Greene

Simon and Schuster, $9.95

——————————————————-

“The meat is excellent, but I have no appetite,” remarks the noble, grief-stricken narrator of Graham Greene’s opulent 21st novel — plain old Alfred Jones, a middle-class voyeur like us — at the climactic title party, in response to a query from the wealthy title host and villain. Then he adds more confidentially, to the reader, “I helped myself to another glass of Mouton Rothschild; it wasn’t for the flavor of the wine that I drank it, for my palate seemed dead, it was for the distant promise of a sort of oblivion.” The same sort of delicious oblivion, one might add, that we normally expect from a new Greene novel — which is the sort that the latest one amply supplies. Read more

This book review originally appeared in the September 10, 1980 issue of The Soho News. Maybe it qualifies less as a book review than as a short polemic, but if I recall this assignment — my first review of a book by Barthes — accurately, I had some space limitations. — J.R.

New Critical Essays

By Roland Barthes

Translated by Richard Howard

Hill & Wang, $10.95

It’s reported that when a celebrated American film critic was asked what she thought of French theory, she replied that the trouble with folks like film theorists is that they forget movies are supposed to be fun. When this response was quoted to me, my heart sank. It made me feel as if all the fun I’d had reading Roland Barthes over the years was no longer legal -– that it wasn’t even supposed to exist.

I’m not trying to pretend here that all of Barthes goes down easily: I still haven’t gotten all the way through S/Z, a favorite among some American lit-crit academics. And I’ll grant you that he may be an acquired taste for puritanical empiricists who mistrust too much sensual, imaginative, and poetic play in their literary puddings — particularly when these occur outside of fiction, and under the auspices of social and aesthetic analysis. Read more