It seems significant that a good many defenders of Inglourious Basterds that I’ve been reading happily buy into the popular myth that scalping is basically something that indigenous Americans did, full stop. It seems that we non-indigenous Americans are still in almost complete denial about our own heritage of genocide in North and South America, which came much closer to succeeding than even the Nazi efforts with the Jews did — an estimated 70 million victims. I assume that some of the indigenous Americans who are still around must be aware of this obscene misrepresentation, but why should we care what they think?

Anyway, here’s some useful information gleaned from the Internet:

Euro-American traditions of scalping

—By Philip Martin

Stereotypes are absorbed from popular literature, folklore, and misinformation. For instance, many children (and adults) incorrectly believe that fierce native warriors were universally fond of scalping early white settlers and soldiers. In fact, when it came to the bizarre practice of scalping, Europeans were the ones who encouraged and carried out much of the scalping that went on in the history of white/native relations in America.

Scalping had been known in Europe, according to accounts, as far back as ancient Greece (“the cradle of Western Civilization”). More often, though, the European manner of execution involved beheading. Enemies captured in battle — or people accused of political crimes — might have their heads chopped off by victorious warriors or civil authorities. Judicial systems hired executioners, and “Off with their heads!” became an infamous method of capital punishment.

In some places and times in European history, leaders in power offered to pay “bounties” (cash payments) to put down popular uprisings. In Ireland, for instance, the occupying English once paid bounties for the heads of their enemies brought to them. It was a way for those in power to get other people to do their dirty, bloody work for them.

Europeans brought this cruel custom of paying for killings to the American frontier. Here they were willing to pay for just the scalp, instead of the whole head. The first documented instance in the American colonies of paying bounties for native scalps is credited to Governor Kieft of New Netherlands.

By 1703, the Massachusetts Bay Colony was offering $60 for each native scalp. And in 1756, Pennsylvania Governor Morris, in his Declaration of War against the Lenni Lenape (Delaware) people, offered “130 Pieces of Eight [a type of coin], for the Scalp of Every Male Indian Enemy, above the Age of Twelve Years,” and “50 Pieces of Eight for the Scalp of Every Indian Woman, produced as evidence of their being killed.”

Massachusetts by that time was offering a bounty of 40 pounds (again, a unit of currency) for a male Indian scalp, and 20 pounds for scalps of females or of children under 12 years old.

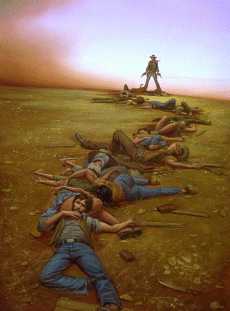

The terrible thing was that it was very difficult to tell a man’s scalp from a woman’s, or an adult’s from a child’s — or that of an enemy soldier from a peaceful noncombatant. The offering of bounties led to widespread violence against any person of Indian blood, male or female, young or old.

Paying money for scalps of women and even children reflected the true intent of the campaign — to reduce native populations to extinction or to smaller numbers so the natives could not oppose European seizure of Indian lands.

Scholars disagree on whether or not scalping was known in America before the arrival of Europeans. For instance, in 1535, an early explorer, Jacques Cartier, reportedly met a party of Iroquois who showed him five scalps stretched on hoops, taken from their enemies, the Micmac. But if scalping in pre-European America occurred, it was fairly rare, certainly not an organized government practice done for money.

Regarding the philosophy of many native tribes, note the following quote, from a man, Henry Spelman, who lived among the Powhatan people and described their approach to warfare: “they might fight seven years and not kill seven men.” (in Kirkpatrick Sale, The Conquest of America, p. 319), Many native societies did not engage in wars of any kind. Native scholar Darcy McNickle estimates that 70% of native tribes were pacifist (in Allen, Sacred Hoop, p. 266).

By anyone’s standards, the Europeans were more skilled and deadly in the practice of war. Paying bounties for scalps was just one of many ways in which the Europeans took warfare to new levels of violence.

The Indians were pulled into warfare against white settlers by rival European factions in America. In wars between the French and British, and between the British and the American colonists, each side encouraged their Indian allies to mount violent attacks on the other’s population.

Popular literature and newspapers loved to describe any Indian attack in great detail in a blood- thirsty, sensational manner. Readers easily believed that Indians were all “savages,” — as that is what the newspapers said. And this helped the government justify its practice of driving native families off tribal lands or killing them.

Almost every fictional account of scalping blames the Indians. The European involvement is over-looked. But it is wrong to do so. Oral history collected from native peoples differs greatly in the interpretation of who was the most cruel, why conflicts were started, or who was defending their family homes from whom.

But it is the victors who write the official history books, and it is the white viewpoint which has dominated our image of the American past.

—From information in Unlearning “Indian” Stereotypes (Council on Interracial Books for Children) and other sources. Philip Martin is a folklorist and book editor for Rethinking Schools. (From www.bluecorncomics.com/scalping.htm)

***

Postscript:

Tarantino speaking with Terry Gross on NPR’s Fresh Air about scalping and Apache Indians (08/27/09):

TERRY GROSS: How did you come up with the idea of scalping, of the Jews scalping the Nazis that they hunt down? Again, it’s this hybrid of World War II and Westerns, but why that?

TARANTINO: Well, it hit me that an Apache resistance would be a wonderful, you know, it would be a wonderful metaphor for Jewish-American soldiers to be using behind enemy lines against the Nazis because the Apache Indians were able, from different points of time, between having 200 braves to 22 braves, were able to fight off for decades both the Spaniards and the Mexicans and the U.S. Cavalry for years because of their — because of their — they were great guerrilla fighters. They were great resistance fighters. And one of their ways of winning battles was psychological battles.

They never did straight-up fights. It wasn’t about, you know, getting killed in the line of fire. It was all ambush, ambush, ambush, and you ambush somebody, and then you take the scalps, and you — even though scalping wasn’t created by the American Indians. It was created by the white man against Indians, and they just took it and claimed it.

But they would, you know, scalp them and desecrate the bodies, you know, tie them to cactuses or bury them in ant hills or things like that, and you know, cut up the bodies and stuff, and then the other enemy soldiers would come across and find their comrades laying there ripped apart, and they would be sickened by it, and it would scare them. It would psychologically get into their heads, so much so that if you thought you were going to be captured — if you were a U.S. Cavalry guy and you thought you were going to be captured by the Apaches, you might kill yourself. If they were with their wives and they thought they were going to be captured, they would shoot their wives for fear of the Apaches getting them.

GROSS: You are part Cherokee. Did you identify with the Indians when you watched Westerns?

TARANTINO: Oh yeah, no, completely. I always did. Yeah, I was always — I remember, like, saying — watching some cowboy-and-Indian movie with my mother, and I go, so, if we were back then, we’d be the Indians, right? She goes, yup, that’s who we’d be. We wouldn’t be those guys in the covered wagons. We’d be the Indians. But the idea of using the Apache resistance, one, it works effective to actually get German soldiers to think of Jews that way. You know, and they’re not just any Jews, they’re the American Jews. They’re Jews with entitlement. They have the strongest nation in the world behind them. So we’re going to inflict pain where our European aunts and uncles had to endure it. And so the fact that you could actually get Nazis scared of a band of Jews, that’s — again, that’s a gigantic psychological thing.The other thing is even the Jews in the course — even though metaphorically aligning themselves with Indians, and you know, you have genocide aligning itself with another genocide.

But the idea of using the Apache resistance, one, it works effective to actually get German soldiers to think of Jews that way. You know, and they’re not just any Jews, they’re the American Jews. They’re Jews with entitlement. They have the strongest nation in the world behind them. So we’re going to inflict pain where our European aunts and uncles had to endure it. And so the fact that you could actually get Nazis scared of a band of Jews, that’s — again, that’s a gigantic psychological thing.The other thing is even the Jews in the course — even though metaphorically aligning themselves with Indians, and you know, you have genocide aligning itself with another genocide.

Thanks, QT. And my apologies for all the sloppy and inexact paraphrases and wrong assumptions deriving from them in this post, which I’ve now deleted. I wish this helped me to like your movie any more, metaphors and all. But at least this is more palatable than what many of your defenders have been saying (and, it seems, assuming) about Indians, as one more proud piece of American knowledge to impart to the rest of the world, like our confident expertise about the Middle East. And thanks to Zach Crowell for sending me this. [8/29/09]