From the Chicago Reader (April 28, 1995). I resaw The Underneath 16 years later, and it still looked good — indeed, possibly even better than any other Soderbergh film I’ve seen since then (although reportedly he dislikes it himself). More recently, it seems that cynicism of various kinds and a preoccupation with prostitution tends to engulf many of his films — perhaps making his filmmaking more appealing to some of my colleagues for this reason, but also making it less appealing to me for the same reason. — J.R.

Kiss of Death Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed by Barbet Schroeder

Written by Richard Price and Eleazar Lipsky

With David Caruso, Samuel L. Jackson, Nicolas Cage, Helen Hunt, Stanley Tucci, Michael Rapaport, and Ving Rhames.

The Underneath Rating *** A must see

Directed by Steven Soderbergh Written by Sam Lowry (Soderbergh) and Daniel Fuchs

With Peter Gallagher, Alison Elliott, William Fichtner, Adam Trese, Joe Don Baker, Paul Dooley, and Elisabeth Shue.

Sound-bite explanations are the media’s preferred means for tackling (i.e., buying and selling) the past as well as the present. Growing up on media images of the end of World War II that evoke relief and euphoria as well as exhaustion, I was hardly prepared for the discovery, in the spring issue of the academic journal October, that according to the respected German filmmaker Helke Sander, approximately 1.9 million women were raped in the territories of the former Third Reich between March and November 1945. The absence of this staggering piece of information from most popular accounts of this period points to a certain incapacity in the way our understanding is structured, not merely a missing block of data. And last week, just after the bombing of the federal building in Oklahoma City, many Americans seemed convinced that it must have been the work of Middle Eastern terrorists rather than, say, more extreme versions of Rush Limbaugh. Because it seemed impossible to imagine how any American could commit so heartless an act, a blank space was created in the imagination that only recent sound-bite demonology could fill — though only four years ago in Baghdad perhaps 500 times as many innocent victims were bombed by this country, experiencing a state of euphoria because it felt it was winning a just war, a slaughter for which no one has been held accountable. Heartlessness, one might say, is strictly in the eye of the nonbeholder.

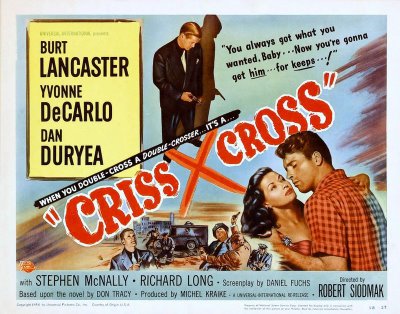

A taste for heartless, sociopathic hoods and sultry femme fatales — a desire to laugh at them and appreciate their outrageousness even as we flinch from them — is certainly part of what links several Hollywood crime thrillers of the 40s with many of those being made today, including such recent favorites as Pulp Fiction and The Last Seduction. The two most recent examples, Kiss of Death and The Underneath, are remakes of Henry Hathaway’s Kiss of Death (1947) and Robert Siodmak’s Criss Cross (1949). The sound-bite version of this is that both are recycled noirs with contemporary settings. But since “noir” isn’t a term American filmmakers or critics or spectators were using in the 40s — and changes meaning today just about every time an academic or a mainstream merchandiser thinks up a new reason for using it — this doesn’t take us very far, except perhaps to the point of suggesting that the flexible noir label serves to keep alive a few 40s Hollywood standbys, like misogyny, fatalism, paranoia, hard-boiled sadism, lyrical and romantic masochism, and a comedy of cruelty — as well as certain iconographic, lighting, and compositional schemes — within a stylish and socially acceptable contemporary context. Remove the noir context from The Last Seduction and the movie becomes misogynist plain and simple; remove it from Pulp Fiction and the movie becomes barbarically neofascist in its worship of the power accorded by guns. Put the noir context back and the stylish gloss renders the subject matter transcendent — sufficiently removed from reality to seem ironic, comfortably couched between smirking quotation marks.

I’m not trying to say that the term “noir” doesn’t have its legitimate uses. Indeed, I would define Criss Cross as a classic noir reeking of metaphysical doom and murky spiritual disorientation, and the original Kiss of Death as a relatively crisp and prosaic documentary-style thriller shot in natural locations like Hathaway’s The House on 92nd St. (1945) and Call Northside 777 (1948), Elia Kazan’s Boomerang! (1947) and Panic in the Streets (1950), and Jules Dassin’s The Naked City (1948). Yet a few elements of the 1947 Kiss of Death are noirish as well. The maniacal leer, cackle, and baby talk of Richard Widmark (his screen debut, which won him an Oscar nomination) as a dandified psycho killer seems derived more from German expressionism — one of the sources of noir — than from docudramas; a few traces of this tradition persist in Michael Madsen’s character in Reservoir Dogs.

In both the new Kiss of Death and The Underneath the filmmakers seem oddly stranded between their models and their desire to say something more contemporary. (Both movies acknowledge the screenwriters of the 40s movies. The first Kiss of Death was based on an unpublished story by Eleazar Lipsky and scripted by Ben Hecht and Charles Lederer; Lipsky retains the story credit in the new version, but Richard Price gets sole credit for the screenplay “based on the 1947 motion picture screenplay” by Hecht and Lederer. Criss Cross was adapted by Daniel Fuchs from a novel of the same title by Don Tracy; the script for The Underneath is credited jointly to Fuchs, who died in 1959, and “Sam Lowry,” actually Steven Soderbergh, the director.) The Underneath — despite its awkward title and some confusion in its focus — is the more impressive of the two films, basically because it succeeds in creating a style of its own, even if it sacrifices part of the meaning of its source to do this. Kiss of Death, which mainly follows the structure of its model while completely transforming the tone, seems too promiscuous and eager to please to have any comparable integrity; it has an absorbing story to tell, but it feels generated more by a committee than by any individual vision. Both versions of Kiss of Death are about a thief who, after being arrested and going to Sing Sing, tries to go straight but keeps getting sucked back into a life of crime by an assistant DA who wants to use him as an informer. The thief initially refuses to cooperate, then changes his mind after his wife dies following her involvement with another gangster. To take revenge the thief fingers other criminals and falsely implicates the gangster as a police informant so that he’ll be wiped out by the mob. Under shifting degrees of police protection for himself and his little girl, and aided by a baby-sitter who becomes his wife — a character who serves oddly as the offscreen narrator in the original version — he moves toward a final confrontation with a psychopathic killer.

Both versions qualify as high-toned hackwork fitfully redeemed by a good story and some incidental pleasures involving the casting and camera work. Perhaps the biggest surprise in the original is how touching Victor Mature is in the lead role. A late D.W. Griffith discovery who languished for most of his career in sword-and-sandal beefcake parts — and was the butt of as many jokes in the 40s and 50s as Schwarzenegger is today — he managed to exceed himself the few times he was cast intelligently, as he was here (and in The Shanghai Gesture).

The remake begins with an elaborate, extended crane shot moving through and around an auto junkyard and environs that effectively maps out a good-sized chunk of the film’s physical terrain. The early sketches of the home life of the hero, an ex-con (David Caruso) trying to stay clean, also promise authenticity. But once he’s dragged by his cousin (Michael Rapaport) into a crooked operation transporting stolen cars, and the standard psycho villain (Nicolas Cage) appears, the movie starts banking on cheap, violent flourishes that take the place of character delineation. The original film had a similar problem with the equivalent villain, Widmark, whose effective performance was designed to be noticed by playing against the style of all the other actors. But even the generic type Cage is embodying seems constructed out of spare parts and loose effects: throwing a drunken driver out of a truck, weightlifting with a go-go dancer instead of barbells, threatening a drunk with a lighted cigarette, mouthing dumb epithets about acronyms and his asthma — each detail contrived to produce a hoot or a whistle rather than build any logic of personality, each pointing back to the scriptwriter rather than the character. Thanks to such stray details, the movie winds up feeling like a series of long, dramatic buildups to payoffs that never arrive.

Caruso doesn’t quite manage to negotiate the star power bequeathed to him by his role and his flashy red hair, but he at least manages to suggest a human being. Rapaport, Samuel L. Jackson, Stanley Tucci, and Ving Rhames do even better with simpler character-actor parts. But the movie’s overall coherence depends on a continuity of character and narrative style, and the determination to turn Cage’s character into a series of disconnected set pieces ultimately splinters both. Not even the impersonal craft and kinky personal inflections of director Barbet Schroeder can bring harmony to the scattershot strategies, which suggest several assembly-line teams of filmmakers working in isolation on separate scenes. (The team that assigned supernatural stealth and prescience to Cage as a potential, unseen kidnapper doesn’t even appear to be on a first-name basis with the one that cobbled together the feel-good ending.)

What survives is a caustic feeling for the corruption of the legal system today that occasionally evokes Deep Cover and was only faintly hinted at in the first version. “Your side of the fence is almost as dirty as mine,” Mature said to Brian Donlevy as the assistant DA 48 years ago. “With one big difference,” Donlevy replied. “We hurt bad people, not good ones.” In fact, Mature wound up getting hurt plenty, but there was only a smidgeon of irony intended in that exchange. Today nobody could buy such a line, yet such is our cynicism that the happy ending manufactured here is even phonier. We don’t believe it, but we want to go home with it anyway.

On the level of plot and thematic coherence The Underneath isn’t a more successful thriller than Kiss of Death, even though Criss Cross is certainly superior to the original Kiss of Death; indeed, it might be argued that Soderbergh’s picture isn’t really a thriller at all, though it uses most of the basic thriller machinery. (You’ll be better off if you check out Criss Cross only after you see the remake.) The reason I still rank it much higher than Kiss of Death is that it’s a gorgeous-looking, wonderfully acted, boldly constructed film with a style, vision, and feel all its own. It may not have enough independence from its source, but it sharply distinguishes itself from the empty, impersonal Hollywood movies that now surround it, neo-noir and otherwise. The director is Steven Soderbergh, whose feeling for mise en scène, actors, and dialogue and whose respect for people in general — characters and spectators — is such that he seems incapable of making an indifferent picture. Even when the root premise is as silly as it was in Kafka, he brings something distinctive to it. And when he’s lucky enough to work with his own script — sex, lies, and videotape, King of the Hill, and here — he can do a lot more than redeem a dubious proposition. In this case, however, he appears to be wrestling with a story that fully engages him only in certain particulars. (The reason he doesn’t take script credit is linked to his chagrin over a dispute with the Screenwriters Guild; “Sam Lowry,” incidentally, is the name of the Jonathan Pryce character in Brazil.) As with Kiss of Death, it seems a given nowadays that the way you “make your own picture” in Hollywood is to start with somebody else’s project and then bore from within; it’s equally clear that without some version of the noir label this project would never have gotten off the ground. The only hitch is that Criss Cross, good as it is, was made almost half a century ago, and Soderbergh’s main interest appears to be the instability of contemporary relationships. Somehow a compromise between these agendas had to be struck.

It’s often been noted by critics that Hollywood noir developed in part out of postwar anxieties related to sexual insecurity and economic instability. Soderbergh is as alert to sexual insecurity in The Underneath as he was in sex, lies, and videotape — though as today’s problem. When it comes to economic instability — which his script, with its countless references to lottery tickets, sports betting, and reckless spending sprees, seems equally attentive to — his interest appears to be more theoretical. (Inadvertently or not, he winds up making economic instability seem like a symptom of sexual insecurity.) And when it comes to the terminal romantic obsessions of his hero, a classic noir fall guy (played beautifully by Burt Lancaster in Criss Cross and quite effectively by Peter Gallagher here), he’s handicapped by his rewrite of the ending, which slightly shifts the focus away from the hero to suggest a more general malaise — spiritual as well as economic and sexual — that informs the world he inhabits. This new emphasis gives the film a potency and moral bite that’s missing from Criss Cross, becoming a subtle indictment of hero and heroine alike, but it also entails a loss of concentration. We’re no longer quite sure what the story is about once it’s over.

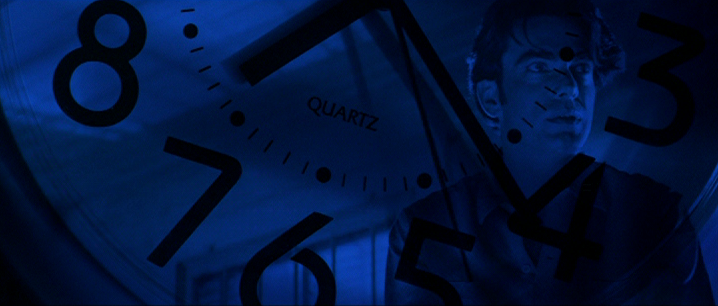

Proceeding gracefully and without difficulty through three or four time frames at once, The Underneath alternates between an armored-car robbery carried out by the hero as an inside job and various stages in his past leading up to it. Criss Cross tells substantially the same story, but more simply, with a single extended flashback planted in the middle of the movie — a sad tale about a divorced lug who can’t get over his wife two years after they’ve separated, even after leaving town for a spell to work at odd jobs. They meet up again and are still attracted. But his former wife, hankering after money, has latched onto a local hood, whom she eventually marries, and things only get stickier. Criss Cross is set in Los Angeles, The Underneath in Austin, Texas (occasioning a cameo by Richard Linklater as a club doorman). Some of the most important other changes involve collapsing the hero’s brother and policeman friend into a single character and substituting a stepfather for his father. The remake builds on the subtle family dynamics found in the original, making these changes a lot more consequential than one might suppose. (By contrast, the fact that the hero of the original Kiss of Death has two daughters and the hero of the remake has only one counts for practically nothing.)

There’s certainly no question about the beauty and the rigor of the film’s visual design, which extends from the giant colored letters that gradually spell out the film’s title at the beginning (a précis of the movie’s narrative form) to the very last shot. This has the best use of ‘Scope framing of any noir project since James Foley’s After Dark, My Sweet (1990) — a movie that’s now virtually lost to film history unless it becomes available again in a ‘Scope format. (Cropped on video, it ceases to exist, and the same will be true of Soderbergh’s movie if it’s cropped — which means that if you don’t see it now you may never get a second chance.)

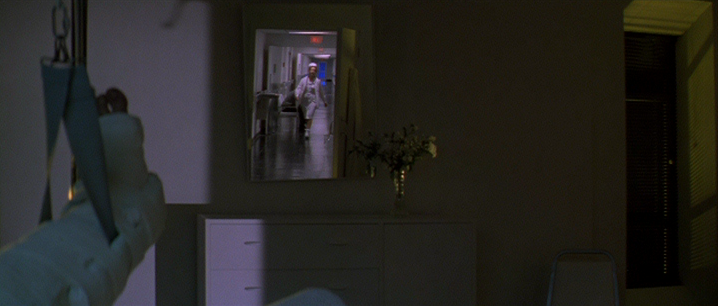

Boldly using color, production design, and diverse camera and lab strategies expressionistically to approximate the hero’s subjective states of mind, The Underneath is far and away the most visually inventive Hollywood picture I’ve seen this year; even In the Mouth of Madness, its nearest competitor, pales in comparison. A couple of sequences where these elements and strategies are combined with ‘Scope framing took my breath away. One features the hero and heroine (Alison Elliott) on opposite sides of the screen, both facing the camera; the hood she’s recently married (William Fichtner) stands between them, his back to the camera, while he kisses and fondles her. One’s eyes dart back and forth like Ping-Pong balls between her hidden responses on screen right and the hero’s improvised lies on screen left, though this is only part of what gives the scene such an unsettling charge. The second, much longer sequence charts the hero’s subjective impressions of floating in and out of consciousness in a hospital bed as various people come to visit him — an extended vamp on a noirish trope that offers a poetic, nightmarish commentary on his own alienation, where the very space of the room seems mutable as each visitor swims into view.

Later in the same setting Soderbergh manages to coax the film’s most interesting performance out of a nonactor named Joe Chrest, playing an ambiguous character named Howard Rodman. (The name comes from the screenwriter who did the uncredited rewrite on Kafka and wrote a segment of Showtime’s Fallen Angel series directed by Soderbergh). Quite apart from all its in-jokes and cross-references, The Underneath is saying plenty about the traps we all dig for ourselves and the swamps that troubled relationships can become. And if the traps and swamps comprising the modus operandi of contemporary Hollywood didn’t keep getting in the way, it would probably say even more. But films are launched and sold (and understood) through sound bites these days, and noir is the generic label that’s selling this movie — even though it has at most an incidental relation to why the film was made or why you should see it. The problem is that without that label there’s little chance people will go — which is why this review has to depend on the same false advertising as the movie.