From the Chicago Reader (December 14, 2001). — J.R.

The Business of Strangers

**

Directed and written by Patrick Stettner

With Stockard Channing, Julia Stiles, Frederick Weller, Jack Hallett, and Marcus Giamatti.

The most notable thing about The Business of Strangers, as Andrew Sarris recently suggested in the New York Observer, may be the conjunction of three facts: that the central character of this first feature is a middle-aged woman executive, that it was written and directed by a man, and that it isn’t misogynist.

This sounds like some PC brief, which isn’t generally a good reason for recommending a film. Yet The Business of Strangers doesn’t have any ideological axes to grind, though it’s interested in ideological exploration. And that points to a kind of respect for its audience, not merely a respect for its leading character.

Several reviewers have noted this picture’s resemblance to In the Company of Men, Tape, and Safe. Though I wouldn’t deny the parallels, they generally have more to do with surface effects than overall meaning. Like In the Company of Men, The Business of Strangers focuses on characters in the business world who display predatory behavior in anonymous surroundings — Anywhere, USA — and it uses a percussive score to suggest these characters’ hostilities and power games. Like Tape, it’s mainly about two characters of the same sex, with a member of the opposite sex serving briefly as a dramatic catalyst, and it has an anonymous setting, a motel or hotel. Like Safe, it’s full of ambiguities about the characters that are never straightened out, and it’s located in a creepy upscale setting. But put all these similarities together and you’re still missing what writer-director Patrick Stettner is up to.

The film runs for a taut 83 minutes, and part of what’s impressive about it is how economically, in a wholly unobtrusive way, it sets up the conflict between the two leading characters, an executive and a woman roughly half her age. Julie Styron (Stockard Channing), the executive, arrives in a city to give a presentation, and is thrown into a tailspin when she hears that her boss is flying into town to meet with her later, which she assumes means she’s about to get fired. As a preemptive move, she summons to town a corporate headhunter she knows, Nick Harris (Frederick Weller), to line up another position for her. Before Nick arrives she gives her presentation, and it’s a disaster, at least in part because Paula Murphy (Julia Stiles), a young woman she hasn’t met who’s bringing materials for the presentation, arrives late. Just after the meeting Julie gets Paula fired.

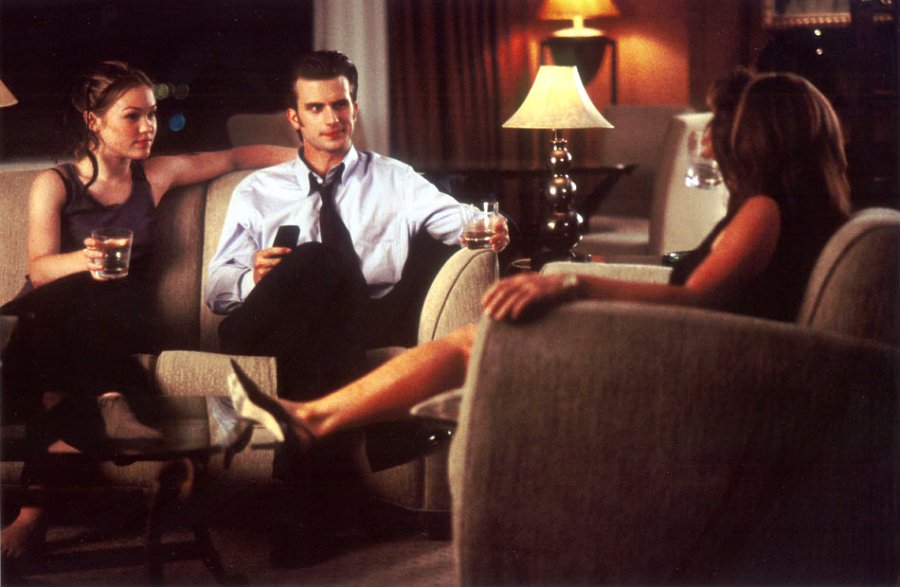

Julie meets with Nick in the lobby of her hotel, then has dinner with her boss, Robert (Marcus Giamatti) — who, it turns out, is about to quit his post and has picked her as his replacement, confident that the board will accept his choice. Slow to take in this unexpected good news and not even sure she’s happy about it, Julie runs into Paula in the bar at the airport hotel. She apologizes for her behavior, promises to get Paula hired again, and offers to buy her a drink. After explaining diffidently that she doesn’t care about being fired, Paula orders a brand of scotch that costs $20 a shot, then asks for a double; Julie asks for the same. It’s the sort of moment one would normally associate with two male buddies or antagonists in a western, and it provides a convenient hinge into everything that follows.

This summary covers only the first 17 minutes of the movie, and it doesn’t include every detail. It leaves out, for instance, the opening credits — a strikingly fragmented, almost abstract sequence showing a plane flattening blades of grass as it prepares to lift off, standing on a runway, and then taking off again, with ambiguous overlaps in between that make the three stages look nonsequential. It also omits many of Julie’s phone conversations (including part of her weekly session with a psychotherapist), her taking a shower in her hotel suite, and a second meeting and conversation between her and Nick. Yet none of these 17 minutes feels especially rushed or telegraphic, because Stettner seems to know exactly what he’s doing, both as a storyteller and as an artist setting up themes and moods.

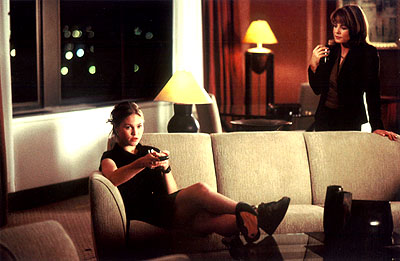

What follows is a lot more uncertain. Over the course of a long and drunken evening together, the two women encounter Nick, whose flight, like Paula’s, has been delayed. Paula quietly tells Julie that he once raped her best friend, and the two women gradually plot a form of revenge.

Or do they? This abrupt development is deliberately ambiguous, and we can’t easily say how much of the revenge plot is Julie’s idea and how much is Paula’s. It would seem that Julie gets the ball rolling, but it’s Paula who decides to put a drug in Nick’s drink, knocking him unconscious. The issue of who’s responsible for what continues as they carry him to another floor in the hotel, which is being remodeled and is sealed off, strip him down to his shorts, and start writing accusatory and inflammatory epithets on his body. The more the plot unfolds, the less secure we are in what we know about Paula — whether she’s truthful, what the state of her mental health is, what her motives are. We’re also somewhat in the dark about Nick. To a large degree, our uncertainty is at the center of the moral questions the film invites us to ask, the most important question being how far are we prepared to go along with — endorse, sympathize with, tolerate, excuse — these women, based on what we know or imagine about Nick?

It’s an interesting and instructive activity, but once our self-interrogation is over, we still don’t have a clear idea of who Paula is or what she’s up to or of what Nick might have done in the past. Furthermore, we may not care much about these things. This is a major limitation, and it makes the film more an exercise or theorem than a fully realized story — Stettner has found an interesting way to bait his audience, but not a lot more. I ordinarily see ambiguity as a Good Thing in movies, but The Business of Strangers dispenses so much of it that Paula and Nick wind up as ciphers — perhaps even bigger ones than they were intended to be.

This movie is clearly a vehicle for two talented actresses, and I can’t fault Stiles for the way her character seems diminished by the abrupt shifts in the plot — it’s as if she were a block of clay being carved away to almost nothing. By contrast, Channing’s character only grows in density, largely because Stettner’s script seems designed to build her in successive layers through her unpredictable responses to what Paula does, and to use Paula and Nick largely as plot mechanisms that serve to challenge the audience as well as Julie. That Stiles is much younger than the character she’s playing — she was reportedly looking forward to starting college after making this film, whereas Paula is plainly a college graduate — surely contributes to the unreadable edginess of her performance; it’s as if the film were saying that the young are inscrutable almost by definition. Nick, by contrast, starts off as a kind of anticapitalist cliche, then becomes slightly humanized by the hint of other layers.

Once Paula enters the movie as an equally important, though much less clearly fixed character, the sense of reality that has previously been carefully established gradually undergoes subtle changes. As Channing correctly described this shift to Dave Kehr in the New York Times, the movie, which “you can’t pigeonhole …as a comedy or a drama…starts in a recognizable reality and goes on a trip with the character [Julie] into a heightened, dreamlike state. It’s almost like dropping acid.”

In fairly quick succession, Paula announces that she’s a nonfiction writer (“I prefer the messiness of real life”) who publishes in literary magazines, flirts with Julie by undressing in Julie’s bathroom with the door open, then kicks the door shut, and a little later apologizes cryptically for her behavior in the elevator (“I’m sorry…. I just wasn’t in the mood,” which implies a come-on from Julie). Apart from a clear sense of class difference that emerges from these and other details — Paula went to Dartmouth, Julie to a community college in Michigan — the relationship between the women quickly boils down to issues of power and who’s in control. It’s clear that to some extent Paula is making herself up as she goes along, but the full extent of her self-definition remains a mystery.

This is an interesting process to watch, and it’s worth noting that the executive producers of The Business of Strangers are David Siegel and Scott McGehee, the ideologically sophisticated writer-directors of Suture and The Deep End. But with only one character in the film we can recognize with any confidence, the ultimate yield is narrow. The film may have been trying to be a generational statement, but Julie’s generation is the only one we wind up seeing clearly.