From the Chicago Reader, July 27, 1990. –J.R.

THE FRESHMAN

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Andrew Bergman

With Matthew Broderick, Marlon Brando, Bruno Kirby, Penelope Ann Miller, Frank Whaley, Maximilian Schell, and Bert Parks.

“The overwhelming attractiveness of the screwball comedies involved more than the wonderful personnel. It had to do with the effort they made at reconciling the irreconcilable. They created an America of perfect unity: all classes as one, the rural-urban divide breached, love and decency and neighborliness ascendant. –Andrew Bergman, We’re in the Money (1971)

Most reviews of The Freshman have understandably focused on Marlon Brando. After all, everybody knows Brando, while hardly anyone is familiar with Andrew Bergman, the writer-director. But a movie as outlandish as this needs to be seen in some sort of context if one is going to make any sense of it, and it seems to me that Bergman is more important to this context than Brando is. It was his script, after all, that lured Brando into his first major role in a decade.

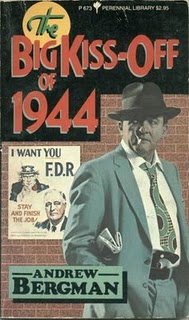

Bergman was born in Queens, the son of a New York Daily News radio and TV columnist named Rudy Bergman, and was an early fan of TV comics like Ernie Kovacs, Victor Borge, and Bob and Ray. In college he studied American history, attending Harpur College and the University of Wisconsin in Madison, where he wrote a dissertation about Depression-era American movies that was published in 1971 as We’re in the Money. He also wrote two detective novels set in the 1940s — one I greatly enjoyed (Hollywood and LeVine), the other (The Big Kiss-off of 1944) I’m still hoping to track down — and a Broadway play that opened in 1986 called Social Security.

Bergman’s screenwriting credits include Blazing Saddles (written with four others), The In-Laws, So Fine, Big Trouble, and Fletch. He also directed So Fine and about half of Big Trouble before being replaced by John Cassavetes. (Cassavetes’ own work on Big Trouble was recut by the producer and the film never got a proper release — making it big trouble for just about everyone — so it’s hard to say who the film “belongs to,” but I happen to find it both funny and Bergmanesque.)

In the early 80s Bergman formed a production company with producer Mike Lobell, which has been responsible for The Journey of Natty Gann (1985) and Chances Are (1989), as well as So Fine and The Freshman. Like most people, I didn’t make it to So Fine (1981) during its short commercial run, but I caught up with this goofy farce on video. It has an exhilarating wildness and a manic energy that are, to my mind, distinctly urban-Jewish in flavor — but a lot closer to the Marx Brothers than to Woody Allen insofar as much of its comedy derives from the warmth, and not merely the cultural conflicts, of family bonds. (It might be noted that the Marx Brothers appear to have a special place in Bergman’s pantheon. As a colleague has pointed out, a name on a fake Italian passport in The Freshman belongs to a character in A Night at the Opera, a movie that clearly inspired the climactic sequence of So Fine; and Pauline Kael has aptly compared Mariangela Metalo, the female lead in So Fine, to Harpo.)

The cumulative impact of The In-Laws, Big Trouble (intended as a sort of In-Laws spinoff), and now The Freshman leaves me no doubts that Bergman is a distinctive auteur with thematic preoccupations and talents all his own. His outrageous plots all involve hapless, innocent heroes becoming trapped inside dangerous, threatening worlds totally outside their previous experience — a bit like Martin Scorsese’s After Hours minus the misogyny, although Bergman’s movies are certainly male-oriented. (The women who pursue and seduce the heroes are often passionate and aggressive, but never predatory; if they’re “dangerous,” it’s usually because of the men they’re connected to.)

Clark Kellogg (Matthew Broderick), a high school graduate from Vermont arriving in New York to study film at New York University, is conned out of his money and luggage by a small-time hustler named Victor (Bruno Kirby). A short time later, they meet again and Victor offers Clark a job with his uncle Carmine Sabatini (Marlon Brando), an Italian importer with an uncanny resemblance to The Godfather‘s Don Corleone.

Sabatini takes to Clark immediately, as does his daughter Tina (Penelope Ann Miller), who, to Clark’s consternation, immediately spreads the word that they’re engaged. Sabatini hires Clark to make a mysterious delivery of what later turns out to have been a Komodo dragon, a giant Indonesian lizard and an endangered species. Clark doesn’t dare refuse, and he soon discovers he’s being trailed by government agents . . .

The rest of this convoluted and slightly insane plot is weird enough to feature both an animal rights extremist (Clark’s stepfather) as a villain and a Mafia chieftain (Sabatini) as a hero, and I’ll hazard a guess that you’ll either find it charming and delightfully funny or extremely irritating.

Although there’s a fair amount of variety among Bergman’s plots, the recurring themes and patterns seem to border on the obsessional. The heroes of both So Fine and The Freshman, for instance, are wrenched out of genteel academia and thrown into a life of crime and high finance — a transition that is not clearly motivated yet is viewed by all the characters as inevitable (a metaphor for Bergman’s own metamorphosis from graduate student to Hollywood screenwriter?). In both cases, academia is viewed as no utopia, but a world that’s every bit as corrupt as the world the hero is forced into. Both movies lavish loving attention on the mutual infatuation between a relatively bland hero and a less educated, more practical-minded father figure steeped in the ethnicity of a particular New York subculture (Jack Warden as Ryan O’Neal’s father, a Jewish garment merchant, in So Fine, and Brando as Broderick’s father substitute in The Freshman).

Both movies have crazed satirical subplots involving aberrations of consumer society — a fad for jeans with see-through bottoms in So Fine; in The Freshman a secret gourmet club featuring outrageously expensive meals made from endangered species. Both movies lampoon aspects of Italian culture and make extensive, self-conscious use of a “found” cultural object that relates to this culture — a production of Verdi’s Otello in So Fine, the movie The Godfather (both parts) in The Freshman. (Appropriated cultural icons can also be found elsewhere in Bergman’s work; Humphrey Bogart, John Garfield, and Richard Nixon all function memorably as characters in Hollywood and LeVine.) More generally, both movies delight in anomalous movie references: the hilarious villain in So Fine is a Neanderthal gangster played by Richard Kiel who is clearly patterned after the monster in Frankenstein; in The Freshman, the Komodo dragon on a leash recalls the leopard in Bringing Up Baby, and a rival family of Italian gangsters is named Minnelli. And both movies feature ice-skating sequences.

None of Bergman’s movies are masterpieces, but most of them are made enormously appealing by their yearning desire to (as Bergman puts it) “reconcile the irreconcilable” — usually different age groups and social and cultural strata — as Bergman claims the better screwball comedies of the Depression did. Unlike Woody Allen’s heroes, whose self-conscious intellectual concerns almost always reflect estrangement from their families, Bergman’s characters tend to bridge cultural gaps without abandoning their intellectual identities. (This is also true in his play Social Security, whose comedy derives largely from the cultural differences between a couple who run a Manhattan art gallery and their middle-class Long Island relatives. The climax of the play features the octogenarian Jewish mother having an amorous fling with a famous painter in his 90s.) In one of the most touching scenes in The Freshman, Clark recites from memory to Sabatini a poem written by his late father; the fact that Sabatini can relate to both the poem and to Clark’s having memorized it points to a bond that transcends superficial differences in their educations and backgrounds. On other occasions, the bridging of cultural gaps becomes the basis for lunatic gags, such as Bert Parks — making his belated film debut — performing a demented version of a Bob Dylan song.

Most reviewers have been describing Brando’s performance in The Freshman as a parody of his performance in The Godfather. I can see what they’re getting at, but I think they’re wrong; as illogical as this may sound, I think the reverse is closer to the truth: Brando’s performance in The Godfather is a parody of his performance in The Freshman.

I happen to be part of the minority that believes that Brando’s Don Corleone is not one of his best acting jobs but one of his worst — a grab bag of facile tricks calculated to call more attention to the impersonation than to the character, which is precisely the sort of hamming that usually wins Oscars. There is reason to believe that Brando would agree — because he refused to accept his Oscar for this role (sending an emissary to the ceremony to speak on his behalf, diverting attention from the film to the plight of Native Americans), and also because he has always shown himself to be one of the most principled and self-critical of American actors, never content to substitute his audience’s assessments of his merits for his own evaluations. But the most convincing argument that Brando is critical of his role in The Godfather can be found in his performance as Carmine Sabatini in The Freshman, which can and should be read as an explicit critique of his earlier part — not a parody, which suggests an exaggeration, but a scaling-down that in fact reveals the earlier part as parodic and overblown.

If Don Corleone was larger than life, Carmine Sabatini is never more (or less) than life-size — a modest character scaled to the dimensions of a particular film rather than a mythical being designed to dominate that film. (To drive this point home, one of the running gags in The Freshman is the degree to which everyone around this character insists on treating him as mythical, in spite of his more earthy qualities.) For better and for worse, Brando’s performance has almost none of the egotism and scene-stealing that marks much of his earlier work; he doesn’t hog all the laughs, and seems happy to accommodate whoever else the scene requires. Ensemble acting seldom wins prizes, but Brando shows himself to be as much a master of this mode as he is of solo flights.

If Brando’s revision of Don Corleone makes him seem more human, this fits hand in glove with Bergman’s own apparent determination to scale The Godfather and its breast-beating profundities (as seen here in a couple of characteristic clips) down to a family romance that is sweeter, earthier, and, above all, less ethnocentric — that is, his scenario conveys a sense of familial bonds that is more existential and less tied to any exclusive ethnic or biological links. As cockeyed as the movie’s plot may be, the social, cultural, and ideological chasm over which Clark Kellogg and Carmine Sabatini meet and fall in love is a plausible view of the splintered American social landscape, cordoned off into special-interest groups and warring allegiances, which only mutual affection can bridge. And the sweet comedy of this encounter between a fatherless college freshman and a sonless godfather fulfills much of the fantasy that Bergman saw in the screwball comedies of the 30s — “an America of perfect unity” in which the usual social divisions are overcome by love and goodwill. If that also happens to screw up our usual moral and social priorities, so much the better.