My column for the Spring 2022 issue of Cinema Scope. — J.R.

My pandemic home-viewing choices are invariably and inescapably matters of chance and accident—basically, what turns up and when. In different ways, all of the dozen items discussed below are examples of what I mean.

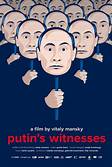

- On its own initiative, Icarus Video sends me Prisms and Portraits: The Films of Rosine Mbakam, a four-disc DVD box set. Three of the four discs fall out of the box as soon as I open it, and I decide to start with Prism (2021). But the disc turns out to be a 2018 documentary by Vitaly Mansky, Putin’s Witnesses, a different Icarus release that has been accidentally affixed with a Prism label, so I watch that instead.

I’m glad that I did. Mansky was an official videographer of Putin’s during the latter’s first year in power, and this lesson in statecraft is valuable not only for its use of outtakes, but also for Mansky’s retrospective and critical voiceovers attached to some of the material he was expected to shoot. The most striking (apparent) outtakes consist of Mansky’s dialogues with Putin about his understandable objections to Putin reinstating the Soviet national anthem to replace the Russian one, and Putin about a year later expressing to Mansky a seemingly sincere preference for democracy over monarchy and autocracy, saying that he foresees and even looks forward to eventually becoming a private citizen again. This comes near the film’s end, and by this time we can fully understand why Mansky couldn’t and didn’t remain Putin’s videographer for very long afterwards. Significantly, the film virtually opens with Mansky’s family’s responses to Putin taking over after Gorbachev’s resignation on New Year’s Eve (his wife, horrified, compares him to Mao), and the film also gives us the responses of Boris Yeltsin and his family to Putin winning his first election.

- Question: Is one’s time better spent watching Preston Sturges’ The Great Moment (1944) —released by Paramount in mangled and truncated form two years after he left the studio, available now on a Kino Lorber Blu-ray — or reading his original script, Triumph over Pain, annotated by Brian Henderson and included in the now out-of-print Sturges collection Four More Screenplays? Answer: Clearly the latter, but I arrived at this judgment only after watching two invaluable extras on the Blu-ray — an almost 40-minute conversation between the late Peter Bogdanovich, Sturges’ son Tom, and film scholar Constantine Nasr about Sturges’ career in general (including such insights as how he managed to escape censorship on The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek [1944]), and Nasr’s 12-minute illustrated introduction to the film. ’Nuff said.

- After I post something on my website about Lev Kuleshov’s The Great Consoler (1933)— an oddball, remarkable early-talkie adaptation of O. Henry stories set in a Russian version of the U.S.—a Facebook friend informs me that he recently purchased a copy of this film from rarefilmsandmore.com, a site I’d never heard of. When I go there, I discover that they also have Howard Hawks’ silent Fazil (1928), which I’ve never seen, and Le parfum de la dame en noir (1931), the second of Marcel L’Herbier’s two delightfully and playfully inventive early-talkie adaptations of Gaston Leroux (the first being the 1930 Le mystère de la chambre jaune).

One apparent catch is that Fazil can only be ordered on the same disc as a 1929 British SF film called High Treason — a requirement that initially annoys me, although this film turns out to be far more fun to watch than Fazil. On the plus side, rarefilmsandmore.com offers streaming samples from both films; on the negative side, both films and samples, plus the L’Herbier, are offered with the wrong screen ratios, and the print of Fazil is lousy to boot.

High Treason is exceptionally silly but hugely enjoyable, not to mention fascinating. It’s a lunatic version of Aristophanes’ Lysistrata, in which the head of the World League of Peace is an ingenue with an all-female staff who all wear the same cute uniform she does — at least until she switches to an evening gown (which makes her easier to identify in long shots), which she puts on for a date with her patriotic soldier boyfriend and wears for most of the remainder of the movie — and who is attended by a wise father who thoughtfully dictates all her major decisions and ultimately becomes the sacrificial patriarchal hero who prevents World War II from breaking out, a crisis brought about by the shooting of border guards who try to uphold the seemingly permanent Prohibition laws. (I swear I’m not making any of this up.) Although its futuristic sets were clearly influenced by Metropolis (1927), director Maurice Elvey is definitely no Fritz Lang when it comes to his crowd management.

- My “repeat engagement” with Alfred Werker’s 1947 Repeat Performance comes about thanks to the arrival of Flicker Alley’s dual-format release of this long-unavailable “noir”—an ahistorical genre category that has been paradoxically legitimized by TCM’s best film historian, Eddie Muller, whose introduction to this release largely addresses the issue of how this speculative fantasy-thriller can or can’t be called a noir (which by now functions more as a marketing label than as an overly coherent critical or generic category).

I first saw Repeat Performance when Muller showed it on TCM’s “Noir Alley,” and the fact that I could re-see it without remembering much of the plot (apart from Richard Basehart’s character) is one sign of both its commercial value for casual viewing and its relative lack of staying power. This means that I could experience Louis Hayward’s strident overacting (especially in his drunk scenes) and appreciate both Joan Leslie and Basehart giving good close-ups as if viewing them for the first time, but also had more spare time to notice (1) the script’s deftness in dodging most of the logical questions raised by the fantasy premise of Leslie’s heroine being allowed to relive her previous year, and (2) my dissatisfaction with those questions remaining unanswered now that I had more time to reflect on them. In any case, Flicker Alley deserves thanks for all its historically centred extras about a film that was sufficiently neglected even upon its release that neither Manny Farber nor James Agee ever mentioned it.

- Haphazard comparisons are provoked by haphazard TV and internet programing, as well as digital objects becoming available for purchase; they’re impossible to avoid, and if the web and TV offerings don’t always correspond to purchasable discs, why should that define the limitations of this haphazard column? Seeing Charles Bickford virtually sleepwalk through his impossible role in William C. De Mille’s 1930 Passion Flower —as an inarticulate lug who marries one heiress (Kay Johnson) only to be lured away by another heiress (Kay Francis) — makes this film a solid disappointment (apart from its feminist viewpoint). This is especially so given that it is an apparent riposte to William’s kid brother Cecil B.’s far superior, raunchier, and even more improbable version of the same cockeyed plot conceit in Dynamite (1929), in which Bickford powerfully charges through his part as an articulate working-class lug who marries an heiress played by Kay Johnson.

By the same token, seeing Bickford play a folksy European fisherman (apparently Portuguese) two decades later in an odd and fascinating noir — George Sherman and Ernest K. Gann’s The Raging Tide (1951), in which he easily outshines his co-stars Richard Conte, Stephen McNally, and Shelley Winters—makes me lament how often he was wasted as a serviceable (rather than memorable) actor in his better-known pictures. Swap him in A Star is Born (1954) with Millard Mitchell in Singin’ in the Rain (1952), and film history remains virtually unaltered. (For the record, Dynamite, Passion Flower, and The Raging Tide are all available on DVD.)

- Around the same time that I read Johann Hari’s fascinating and informative but often blood-curdling 2022 book Stolen Focus: Why You Can’t Pay Attention—and How to Think Deeply Again, I decide to indulge my fondness for early Russian talkies in general, and ’30s musicals by Grigori Alexandrov in particular, by watching his Circus (1936) with English subtitles on YouTube, which I enjoy so much for its campy cinematic inventiveness, exuberance, and many surprises (including a biracial theme) that I order it on DVD from eBay. (The Russian DVD version turns out to be expertly and effectively colorized, although I have no way of knowing if Alexandrov was involved or gave approval.) Alexandrov is mainly known to us Yanks as Eisenstein’s long-term collaborator, credited as co-director on many of his features, but his cheerfully manic early musicals deserve to be as well-known in the West as they once were in Stalinist Russia. (It’s rumored that his Volga-Volga [1938] was a particular favourite of Stalin himself.)

Around the same time that my Circus DVD arrives, I re-see Alexandrov’s 1934 Jolly Fellows (a.k.a. Merry Fellows, a.k.a. Moscow Laughs), reportedly the very first Russian musical, which yields equivalent amounts of crazy knockabout fun. (If Circus periodically evokes Busby Berkeley at his giddiest, Jolly Fellows veers from anarchic barnyard slapstick to madcap city adventures that suggest both Spike Jones and Spike Jonze.) Yet given Hari’s observations about the “surveillance capitalism” by which merchants spy on all our online activities in order to serve up items that cater to our most infantile desires, I’m starting to wonder if my relatively non-deep appreciation of Alexandrov has been stoked by my eBay purchase and then further tweaked by my version of YouTube Premium, which I’m paranoid enough to speculate may not be the same as yours. If it isn’t, then the very suppositions about shared culture that helped to launch this column over two decades ago may sadly be turning anachronistic. But I hasten to add that if you place “Alexandrov English subtitles” in your YouTube Premium search engine, you too can join in the shallow surveillance capitalism fun without even purchasing a DVD.

- The great advantage of The Last Tycoons (2020), a French TV miniseries on a two-disc DVD box set from Icarus Films, is that it takes on the previously neglected and fruitful topic of French film producers—including, among many others, Robert and Raymond Hakim, Mag Bodard, Pierre Braunberger, Pierre Cottrell, Anatole Dauman, Marin Karmitz, and Jacques Perrin. The disadvantage is that such a topic can’t be organized into a series without oversimplifying or overlooking many ancillary topics, e. g., films. I assume this is why or how actress Macha Méril can offer the absurd and uncorrected howler that Belle de jour (1967) was Buñuel’s first film in colour — in fact, the Hakim brothers contractually assured him he could shoot in black and white but then persuaded him to ignore that clause, so presumably explaining that Buñuel had already made colour films in the ’50s would have taken too much time and confused the issue.

The eight parts of the series are built around such shortcuts, from their titles — e.g., “The Romantic Ones,” “The Tenacious Ones,” “The Audacious Ones,” “The Magnificent Ones,” thereby implying that the producers spotlighted in each respective episode couldn’t possess more than one of these qualities — to the fact that each part is centered on no more than three films, most often ones with high profiles such as La belle et la bête (1946), Nuit et brouillard (1956), and Á bout de souffle (1960). Still, a lot of interesting and colourful information is imparted, and it’s fascinating to discover how many of the older New Wave producers were Holocaust survivors.

- A high school drama teacher once told me that actors tended to be either smarter or dumber than other people, regardless of how intelligent they were as performers. Like other neat formulae, this can turn into oversimplification, but it came to mind as relevant while I was watching the writer-director of Doubt (2008), John Patrick Shanley, conversing in a bonus of the Blu-ray edition of the film with his two stars, Philip Seymour Hoffman and Meryl Streep. I missed Doubt when it came out (it was the same year I retired as a regular reviewer) and only caught up with it 13 years later, mostly because of my admiration of Hoffman, who was conceivably the most versatile American actor since Brando in the ’50s; it strikes me as a masterpiece, with Viola Davis performing as brilliantly in her smaller part as Hoffman and Streep do in theirs. And in their conversation with Shanley, Streep is as smart as she is in her role — above all, when she lucidly explains how a theater audience can accept uncertainty about character or plot more readily than a movie audience — whereas Hoffman comes across as boring and relatively clueless, suggesting that all his ingenuity in creating his own ambiguous character went into his performance.

- My most expensive digital purchase in 2021 was Gaumont’s two-disc Blu-ray of Louis Feuillade’s magnificent 1919 serial Tih-Minh, which cost me 50 Euros from French Amazon (including postage) but was well worth it. By now I believe I’ve seen this Côte d’Azur adventure four times: first, the seven-hour print without intertitles held by the Brussels Cinémathèque; then the shorter but intertitled print held by the Paris Cinémathèque; then the grubby and blotchy version that circulated online; and finally, the beautiful 2018 restoration carved out of the Brussels version on the Gaumont Blu-rays, which is the best of the lot. Never has the film’s deep-focus cinematography and almost cosmic sense of physical scale (with its literal cliffhangers) looked more spectacular. Yet even though my distant memories might be fooling me, I miss one sequence from the Brussels version (which I think I saw over half a century ago at the Museum of Modern Art), which showed high-society types smoking hashish or opium on the floor of a salon. Maybe I dreamt it—I can’t even remember now whether these were the good guys in the Lucile Villa or the bad guys in the Circe Villa, given that in the serial as a whole, civilization and culture often seem to be associated with gentility, often to the point of inertia. In the early episodes, the only visible activity of the eponymous, half-breed heroine, who is suffering from some form of perpetual hypnotic trance, is gathering and arranging flowers—although, like one of her thornier picks, she scratches the face of a villain named Marx after he kills her father and a family servant. And the true hero of the serial isn’t her handsome, Hefner-like fiancé (a true layabout), but the Villa Lucile’s butler and his fiancée, a maid, both of whom have the most energy and ingenuity.

- I’ve twice had the experience recently of seeing a thriller as if for the first time after having written about it. Specifically, I reviewed John Badham’s assassination thriller Nick of Time in 1995, and then forgot it so completely that I could watch it 26 years later without remembering it, and liked it so much that I ordered it on a Paramount DVD (no extras), accessing my review only later. Even worse, I reviewed a French DVD of Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s 1946 thriller Somewhere in the Night (which, significantly, is about amnesia) in this column in the Fall 2016 Cinema Scope, but had completely forgotten it by the time I unknowingly re-saw it five years later.

How could this happen? Here’s my theory. Insofar as I’m pushing 79, I’m occasionally suffering short-term memory losses; but in addition to that, most thrillers are designed to overtake a viewer’s attention with their pure linearity, and then to go up in a cloud of disposable smoke as soon as their mysteries and other narrative uncertainties are resolved. So, especially if you’re a reviewer ready to turn your attention to other things, these are experiences designed to be forgotten, no matter how “effective” they are in transit.

- One reason why I haven’t forgotten (and won’t forget) Kirsten Johnson’s Dick Johnson is Dead (2020) — which I saw online recently before I started sampling the generous extras on Criterion’s Blu-ray — is that it explores not only how to die but also how to live gracefully, thoughtfully, and even comically, with certain amounts of dignity even while thinking about death’s rude indignities.

- Béla Tarr has no problem discussing his own films, as long as this concerns how he made them, not what they’re about. (I once attended a four-hour lecture for his FilmFactory students in Sarajevo in which he explained how he did every shot in Sátántangó [1994].) Consequently, if you’re looking for clarification about the meaning(s) of his Damnation (1988), beautifully restored on a Blu-ray from Arbelos Films, you’re far better off viewing the new interviews with actor Miklós Székely and composer Mihály Víg, reading the new essay by Jay Kuehner, or even consulting the archival newsreels from the Oroszlany and Dorog coal mine included with this release than you would be watching the new interview with Tarr included on the disc. Better yet, simply watch Damnation again.