From the Chicago Reader (October 4, 1991). — J.R.

HANGIN’ WITH THE HOMEBOYS **** (Masterpiece)

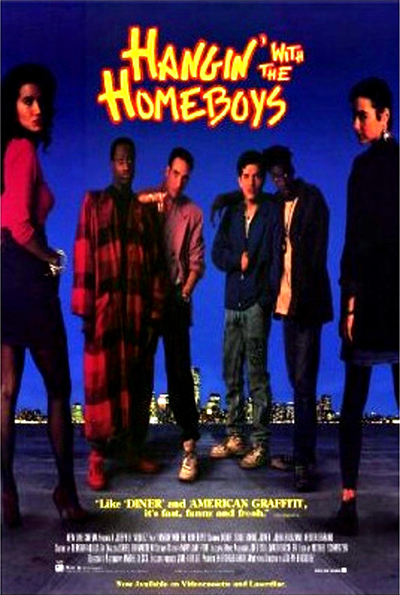

Directed and written by Joseph B. Vasquez

With Doug E. Doug, Mario Joyner, John Leguizamo, Nestor Serrano,

Kimberly Russell, and Mary B. Ward.

Sometimes wonderful movies just don’t have a chance. Hangin’ With the Homeboys is more truthful, more fully realized, and more densely felt than Jungle Fever, Up Against the Wall, Straight Out of Brooklyn, Boyz N the Hood, and Livin’ Large. But it’s turned up after these others, and it has fewer calling cards: no stars, no violent deaths, no preachy slogans, no film-festival hoopla or media hype. And it has a lousy title to boot, one that sounds like a movie you’ve already seen but remember only vaguely. (I wanted to give this movie a better chance by making it a “Critic’s Choice” last week, but the paper was already loaded with them.)

After Dave Kehr’s rave review in the Tribune a week ago, however, I had some hopes for the film’s chances. And wanting to take a second look, I caught the late show at the Broadway the same night. The others who were there seemed to love the movie as much as I did, but there weren’t very many of us. (I suspect the movie was better attended when it showed Thursday at the Chicago Latino Film Festival, where its writer-director was in attendance.)

If this movie had also opened at Webster Place or Water Tower, I think it would have garnered a much larger and no less appreciative audience. But that’s dreaming of utopia. It’s not the sort of movie that would ever turn up at those theaters, no matter how funny, wise, moving, powerful, or entertaining. Movie exhibitors and distributors, in their wisdom, have decided that a buddy movie whose leads are two blacks and two Puerto Ricans belongs at Chestnut Station, Hyde Park, the Bel-Air Drive-In, and Broadway, not more upscale houses where yuppie white-bread fantasies like The Fisher King, Rambling Rose, Deceived, Dead Again, City Slickers, and The Doctor tend to dominate.

For more than half of this century, movie audiences weren’t “targeted” through a divide-and-conquer strategy the way they are now. Even when the theaters themselves were segregated, people of all classes, races, and ages usually went to the same movies. Now that we’re all divided into categories and expected to see “our own” movies at “our own” theaters — largely, it would seem, to serve the business schemes of others — we often get herded into choices that we might not otherwise have made, and movies that we might have liked get lost in the shuffle.

Hangin’ With the Homeboys covers less than half a day in the lives of four guys from the south Bronx looking for kicks on a Friday night. It starts off with a deceptive yet funny and ultimately relevant precredits prologue that exists outside the time scheme of the story. And before we’re properly introduced to the “homeboys,” who are in their 20s, we see one of them, Willie (Doug E. Doug), riding on the subway; suddenly the three others — Tom (Mario Joyner), Johnny (John Leguizamo), and Vinny (Nestor Serrano) — burst into the car. Tom starts baiting Willie, who responds in kind, and before long Tom, Johnny, and Vinny are pinning Willie to the floor — thereby terrorizing the white onlookers — and preparing to stomp on him. Then Willie breaks the spell, bursting into laughter, and Tom grandly announces to the aghast strangers: “Ladies and gentlemen, you’ve just been watching another performance of ghetto theater . . .”

So we have, and the ghetto theater that follows plays more subtly with other kinds of ethnic stereotypes — apparently affirming them at first but ultimately complicating and humanizing them, juxtaposing them with one another and then undermining them through these juxtapositions. What’s deceptive about this opening is that it promises a certain self-reflexivity in the movie — but that’s immediately dropped (at least on the surface). Before long we discover that Tom is an aspiring actor, and much later in the movie he and Willie break into another mock fight in an upscale billiards parlor; their gag routine incidentally allows Tom to show off his acting prowess. But what the scene does to and for us at the beginning is to declare that our preconceived ideas about these ghetto types are going to be both verified and overturned.

Each character initially strikes us as a certain kind of ethnic stereotype. Willie, who’s black, lives on welfare, borrows money constantly, and accuses anyone who criticizes him of being racist. Vinny, who’s Puerto Rican, is a Romeo who lives off his girlfriends and pretends to be Italian (his real name is Fernando). Tom, who’s black, is a go-getter who sells magazine subscriptions over the phone while trying to get ahead as an actor. (His main claim to fame is that he almost got the part of a waiter in Rain Man.) Johnny, another Puerto Rican, is a sexually inexperienced grocery clerk, still undecided about whether he wants to go to college, who has a crush on a female customer he’s convinced is innocent and virginal.

We get to know these people better, however, and then we see that their similarities and differences — which may be part of the stereotypes — spark their interactions. Willie and Vinny are both shiftless, Tom and Johnny are hardworking; Vinny and Tom are suave, Johnny and Willie are socially awkward; Vinny and Tom are generally cheerful, Willie and Johnny are often depressed. And they keep tweaking one another about these traits. Each young man has at least one illusion shattered over the course of the night; as we get to know them, our own illusions about them are shattered as well.

After I saw this movie for the first time I learned that Joseph B. Vasquez, the writer-director, is half black and half Puerto Rican. At the very end of the movie, he dedicates it to “those who inspired it, the homeboys of my youth,” and affectionately lists nine of them; but on some level, I suspect, all four of his heroes are also different parts of himself. Vasquez is no neophyte — he’s directed a couple of low-budget features, which I haven’t seen, Street Story and Bronx War. And his actors are all consummate professionals; three of them — Doug, Joyner, and Leguizamo — are mainly comics. What this collective expertise makes possible is a kind of symmetrical distribution of traits among the characters, and as a result they spark and illuminate one another at every turn.

“When all the archetypes burst out shamelessly,” Umberto Eco has written of Casablanca, “we plumb Homeric profundity. Two clichés make us laugh but a hundred cliches move us because we sense dimly that the cliches are talking among themselves, celebrating a reunion.” On an immediate level, part of the beauty and freshness of Hangin’ With the Homeboys is its relative freedom from cliché, its characters’ lifelike complexity, which makes it quite different from a movie like Casablanca. But on a deeper level, it does explore ethnic stereotypes — cliché of a sort — delving into their truth as well as falsity. By allowing these stereotypes to talk among themselves, celebrating a reunion, Vasquez is subtly reconstituting them so that they come closer to their real-life models; he sets up a kind of moral geometry between them, canceling out their banalities and enhancing their elements of truth. Each of the homeboys is individually a kind of cliché; but together, in complex interaction, they keep one another honest and believable.

Willie, for instance, starts out as the most comically self-deceiving and self-serving, trotting out the accusation of racism every time he’s thwarted or challenged. Yet he’s also Johnny’s best friend — tender and understanding about his sexual naiveté where Vinny, for instance, mainly shows contempt. (Later we begin to understand that Vinny displays such rancor because he himself used to be a similar sort of romantic.) Though Vasquez never ceases to show us that Willie uses racism as a knee-jerk alibi for inertia, he also shows us to what degree racism actually does figure in his everyday existence, eroding his faith in his own future. The last time we see Willie — in the wee hours, when he’s glancing around at much older black men in a coffee shop — we can instantly share his rage and horror at what his life seems to hold in store (something Vinny has mockingly alluded to earlier). In the final analysis, Willie is the most tragic of the four.

The point of such shadings isn’t to mount any sort of general thesis about sexual experience, friendship, or racism, but to offer us the yin and yang of each character — and meanwhile to tell us, almost incidentally, about the kind of everyday existence shared by these four. Johnny may be hopelessly innocent, but he’s the only one who might be said to have scored romantically over the course of the long night: he’s picked up and befriended by a flirtatious, cheeky college girl (Mary B. Ward, in a lovely, perfectly articulated performance) while Vinny can’t even get to first base with her. Tom, the one who appears to have the most going for him, winds up losing the most — and losing it in such a way that we wonder how much he really had to begin with, how much his self-confidence is an acting job designed to fool himself.

Vinny is in some ways the most pathetic of the homeboys, but he also seems the most unflappable; he’s humiliated by an Italian-American cop, rebuffed by countless women, and knocked to the group by Johnny, but by the end he’s still carrying on as if nothing has happened. After the opening credits, he’s the last of the four to be introduced, and he’s the last one we see in the movie; both times, he’s waking up and proceeding to business as usual.

The most common failing of the macho buddy movie — especially of the “boys’ night out” genre — is its treatment of women; by placing us in complicity with a group of rowdy males, we’re usually coerced into sharing their fears, delusions, and resentments toward women. This movie never comes close to that form of demagoguery. Certainly the homeboys have their brutish moments — in an early scene, Vinny, Willie, and Tom place cash bets on how Tom’s girlfriend will rate physically on a scale from one to ten. But the women all have voices and identities independent of the heroes’ conceptions of them.

As it goes on this movie gains in density, because we’re never allowed to stay for long within one character’s vantage point. Each homeboy is deluded in some way about himself, but each sees the others with a relative clarity that we come to share. We want to know what happens to these people after the picture is over, because whatever their failings, we see them as friends. It’s too bad that we can only see them in certain neighborhoods; for some of us, that means we’re bound to lose touch with them — as well as with some part of ourselves.