From the Chicago Reader (December 2, 1994). — J.R.

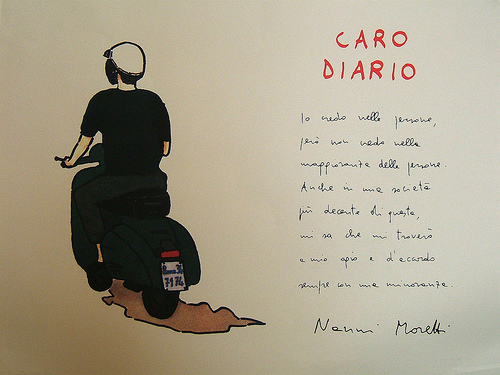

Caro Diario (Dear Diary)

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Nanni Moretti

With Moretti, Jennifer Beals, Carlo Mazzacurati, Renato Carpentieri, Antonio Neiwiller, and Mario Schiano.

How many movies put us in touch with real people as opposed to stars and characters? Not very many, perhaps because we tend to go to movies to escape people — or at least to encounter them in more circumscribed and protected ways than we would in real life. Thanks to movies and TV, a good many of us think of some real people as heroes, villains, and other stock figures; witness the recent election campaigns.

One form of literature, and by extension, one form of film that’s designed to place us directly in contact with individuals is the personal essay. According to writer Phillip Lopate — an expert theorist and practitioner of the form whose invaluable anthology The Art of the Personal Essay was published earlier this year — “The hallmark of the personal essay is its intimacy. The writer seems to be speaking directly into your ear, confiding everything from gossip to wisdom. Through sharing thoughts, memories, desires, complaints, and whimsies, the personal essayist sets up a relationship with the reader, a dialogue — a friendship, if you will, based on identification, understanding, testiness, and companionship.”

Lopate is also a sensitive film critic and in the winter 1992 issue of the Threepenny Review devotes one of his own essays to defining, describing, surveying, and celebrating “a cinematic genre that barely exists” — namely, the personal film essay. Four of Lopate’s key examples are Alain Resnais and Jean Cayrol’s Night and Fog, Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil, Orson Welles’s Filming Othello, and Ralph Arlyck’s An Acquired Taste, though a large part of his essay is devoted to explaining why several other candidates — including Jon Jost’s Speaking Directly, Yvonne Rainer’s Privilege, Jean-Pierre Gorin’s Routine Pleasures, Welles’s F for Fake, Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Notes Toward an African Orestes, and Michael Moore’s Roger & Me — don’t quite make it into his pantheon.

By his own admission, Lopate is somewhat hampered in his search for personal film essays by his desire for them to conform to his literary definition of the form while still qualifying as expressive in film terms. And some films that do measure up to his literary definition are just plain bad: a fairly recent example of my own choosing would be Andrei Codrescu’s glib and borderline insufferable Road Scholar. However, in an article about this year’s New York Film Festival in the November-December Film Comment, Lopate appears to have added a new title to his master list — Nanni Moretti’s Caro Diario (Dear Diary), which is currently playing in Chicago. “As a lover of movies and essays,” Lopate writes, “this is a film I’ve been waiting for all my life.”

Moretti, born in 1953, has cult status in Italy and France as a comic writer-director-performer. He’s made eight features to date, but Dear Diary is the first to be commercially distributed in the U.S. Given the small percentage of foreign films we’re able to see here anyway, this shouldn’t be very surprising. I’ve only seen two of his previous films, La messa e finita (The Mass Is Over, 1985) and Palombella Rossa (Red Lob, 1989), and still have to catch up with Io sono un autarchico (I Am Self-Sufficient, 1976), Ecce Bombo! (1978), Sogni d’oro (Sweet Dreams, 1981), Bianca (1984), and La cosa (The Thing, 1990) — the last an hour-long documentary about the Italian Communist Party. Moretti has never been a party member himself, though the subject appears to be one of his key preoccupations, which is probably another reason for his stateside invisibility. Foreign films that tell us too much about things we don’t know about — films that are bound to make New York Times reviewers testy, and not even testy in an essayistic manner — don’t get distributed here.

A maverick in the Italian film industry, Moretti never went to film school or apprenticed with a more established director, unlike all his best-known colleagues. He shot all his early shorts and his first feature in Super-8, and his second feature in 16-millimeter with direct sound (as opposed to postsynchronized dialogue, the standard for Italian movies). Only in his third feature did he begin shooting in 35-millimeter, and he reverted to 16 on La cosa. Over the past several years, he has also branched out into producing and exhibiting. His art house cinema in Rome, the Nuovo Sacher (named after his favorite dessert, the Sacher torte) shows independent films from all over the world.

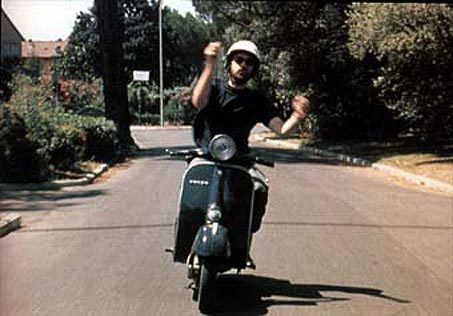

Dear Diary is the first of Moretti’s films in which he appears as himself rather than a fictional character named Michele. (Though Michele has different professions in each movie — filmmaker in Sweet Dreams, math teacher in Bianca, priest in The Mass Is Over, and communist politician in Red Lob — his character is reportedly pretty much the same.) It also differs in adopting a pseudodocumentary mode so seamless that many reviewers have mistakenly regarded this film as a straight documentary rather than an adroit imitation of one. Moretti divides the film into three discrete and very different sections — “On My Vespa,” “Islands,” and “Doctors” — described as chapters in his diary and accompanied by his offscreen narration. Though each mixes documentary and fiction in a somewhat different manner, this may not be immediately apparent.

“Islands,” for instance, is about a wholly fictional visit paid by Moretti to a friend named Gerardo (Renato Carpentieri), who has been living for 11 years on the island of Lipari, where he has devoted himself to studying Joyce’s Ulysses. Moretti goes there hoping to get some work done (apparently he’s scripting Caro Diario) but when he finds himself getting distracted he and Gerardo travel to several other nearby islands off the north coast of Sicily — Salina, Stromboli, Panarea, and Alicudi — in search of quieter surroundings. One of the main comic themes here is Gerardo’s intellectual contempt for television, which he hasn’t looked at in years. As he and Moretti proceed farther and farther away from civilization (on boats equipped with TV sets), his seeming indifference quickly grows into an obsessive fascination with TV, especially American soap operas. After they climb all the way up to the smoking rims of the volcanoes of Stromboli — the same spectacular location used at the climax of Roberto Rossellini’s Stromboli (1950) — Gerardo sends Moretti off to ask some nearby Americans about an upcoming episode of Santa Barbara that hasn’t aired in Italy yet.

“Doctors,” on the other hand, restages a series of events that actually happened when Moretti found himself suffering from an extreme itching on his arms and legs, and each of the doctors he consulted reached a very different conclusion and prescribed very different medication. Though the presentation of this story is relatively straightforward, and is documentary in appearance, I’m told that all the doctors — with the exception of a couple of Chinese acupuncturists — are played by actors.

“On My Vespa,” the first chapter, combines the methods employed in “Islands” and “Doctors,” though not always in obvious ways. It follows Moretti as he drives around Rome on his scooter — exploring various neighborhoods and occasionally stopping long enough to see a movie, peer in a courtyard, visit a street dance, or chat with a pedestrian. Most of this can be taken as a graceful and amiable travelogue, a sort of freewheeling documentary. But many — perhaps all — of Moretti’s encounters with pedestrians are staged. (One of these is with Jennifer Beals, who’s seen walking with her husband, director Alexandre Rockwell. Moretti compliments her on Flashdance, but he doesn’t seem to realize she didn’t perform the dancing in it.) Moreover, one of the two movies Moretti sees — a contemporary Italian feature in which three characters discuss recent changes in society — is not a real movie but a clever pastiche, filmed by Moretti for the purposes of this sequence. The other film he sees is Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, dubbed into Italian. Moretti finds the film so depressing that he seeks out the author of the pretentious and favorable newspaper review of the film that he had copied into his diary and then insists on reading the review aloud to the critic, who moans in protest from his sickbed.

What ties all this material together is the force and humor of Moretti’s eclectic personality. In each chapter he takes on a different role — as subject in “On My Vespa,” as object in “Doctors,” and chiefly as straight man to the comic behavior of others (Gerardo, the mayor of Stromboli, various children and parents) in “Islands” — suggesting that Dear Diary is three essays rather than one. But the subtle carryovers of themes and attitudes from one chapter to the next is actually one of this movie’s strongest pleasures. For example, TV, a central theme of “Islands,” crops up significantly, if obliquely and grotesquely, in the clip from Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer.

I tend to be a compulsive notetaker at movies I intend to review, and I think it says something about the distinct yet elusive flavor of Dear Diary that I found the film virtually impossible to annotate; neither descriptions of the images nor quotes from the narration or dialogue capture its essence, which is the essence of Moretti himself. Other reviewers have been so stumped by this problem that they’ve compared Moretti to Woody Allen — an act of simple desperation that conveys next to nothing about Moretti’s persona, intelligence, politics, or filmmaking style, which have little to do with one-liners or aping the mannerisms of other directors. To get some measure of Moretti’s superiority to Allen as a filmmaker, all one has to do is compare their selection and use of music. The difference between Allen using “Rhapsody in Blue” in the opening sequence of Manhattan and Moretti matching a Keith Jarrett piano solo with his visit to the site of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s murder at the end of “On My Vespa” is like the difference between decorative wallpaper and nuanced mural painting.

Equally misguided, I think, are efforts to link Moretti with Chaplin, Keaton, or Tati — though Dear Diary does echo Chaplin’s desire to sound off about anything and everything in A King in New York, and there are a few hints of Tati’s feeling for the everyday and his idiosyncratic and offhand way of developing gags. If Moretti remotely resembles any American comic in his neurotic isolation and his crabbiness, it would probably be Albert Brooks. But on the whole I think it would be much more fruitful to see him as triumphantly Italian, not as yet another failed imitation American.

During my first visit to Rome a couple of years ago, what struck me most about the city was its homey lack of pretension (in comparison to Paris, Berlin, or Vienna) and its relaxed feeling of intimacy, both of which are beautifully conveyed by Moretti in his travels through the city and his casual encounters with strangers. Similarly, his encounters with landscapes, and people in “Islands” and with medical experts, as well as his own mortality, in “Doctors” are not merely satirical commentaries on the way we all live, but, more specifically, detailed forays into the textures of life in contemporary Italy. We experience these textures so directly because we see them through the everyday subjectivity of a unique individual, not a generalized hero or an abstract camera placement. The effect of a single voice brings us closer to the filmmaker, as though Moretti were personally drafting a private letter to each of us.

If the airy simplicity and open-ended freedom of Moretti’s method leave the viewer with an unexpectedly weighty and mysteriously unified impression — at once buoyant and melancholy, witty and wise — this may be because, unlike most pictures, this one puts us in touch with another human being. And as Montaigne, the granddaddy of all personal essayists, put it, “Every man has within himself the entire human condition.”