From the Chicago Reader (September 29, 1995). — J.R.

Homework

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Abbas Kiarostami

Through the Olive Trees

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Abbas Kiarostami

With Hossein Rezai, Tahereh Ladanian, Mohamad Ali Keshavarz, Farhad Kheradmand, and Zarifeh Shiva.

At the Toronto film festival earlier this month Canadian filmmaker Clement Vigo recalled the memorable response of Winston Churchill to pressure to cut state arts funding during World War II: “If we cut funding for the arts and culture, then what are we fighting for?” It’s a question I’ve been pondering ever since.

A month earlier, while I was in the middle of looking at close to 100 films as part of the New York film festival’s selection committee, I had the rare privilege of being able to fly for a weekend to still another festival, in Locarno, Switzerland, to serve on a panel devoted to Godard’s Histoire(s) de cinéma. Locarno had two ambitious sidebars this year — one devoted to Godard’s video series, the other to Iranian women filmmakers and the first virtually complete retrospective of work by Iranian master Abbas Kiarostami ever held anywhere, including an exhibition of his color photographs of landscapes and two very beautiful paintings. Some of the films shown were the only existing copies. I’m told a shorter version of this retrospective will circulate if duplicate prints can be made, and the Film Center hopes to show it.

Both Godard and Kiarostami could be described as creatures of state funding, hence representatives of what Churchill argued a country should fight for and what Newt Gingrich would contend we can and must learn to live without. Interestingly enough, in a letter to the New York Film Critics Circle last January, Godard paid tribute to Kiarostami, lamenting his inability “to force [the] Oscar people to reward Kiarostami instead of Kieslowski.” Without question the best films I saw over three days in Locarno were all by Kiarostami, apart from an untranslated 21-minute film about a leper colony (The House is Black, 1962) by the great Iranian woman poet Forugh Farokhzad (1935-’67), an extraordinary poetic reverie I don’t expect to forget anytime soon.

Thanks to the Locarno windfall and some previous screenings in Chicago and elsewhere, I’ve now seen over half of Kiarostami’s oeuvre, including his earliest and most recent films — seven of his dozen features and five of his ten surviving shorts — and I’m more convinced than ever that he’s one of the giants of contemporary world cinema. (For what it’s worth, Akira Kurosawa feels the same way; a year or so back he said that Kiarostami was perhaps the only living filmmaker who could fill the gap left by the death of Satyajit Ray.)

It’s too bad that Miramax, which is distributing his most recent feature, Through the Olive Trees, doesn’t agree — or, more precisely, has been ensuring that most Americans won’t know who Kiarostami is. Judging from its behavior, Miramax’s notion of a giant coincides with Gingrich’s — someone who pulls in a profit by any means available, not someone whose art and vision changes the way we experience the world. Not surprisingly, after Miramax unceremoniously dumped Kiarostami’s film — the first and so far only Iranian film ever to receive U.S. distribution — in New York last spring, without any press shows or ads to speak of, most of the press and public ignored it. One of the major art-house programmers in Chicago tried to book the film, only to be told it wasn’t available because Miramax was withdrawing it from distribution. The Film Center did succeed in booking it for two screenings, this Saturday and Sunday, to launch its current Iranian retrospective. (Kiarostami’s documentary Homework, which fortunately isn’t in Miramax’s clutches, will also be shown on both days.) But when the Film Center tried to get a print of Through the Olive Trees early enough to screen for the press — or, barring that, a video for preview purposes — they were less lucky. So to write about it I have to depend on my memories of the film, which I saw twice more than a year ago.

Many critics would simply accept Miramax’s judgment that the greatest of all Iranian filmmakers isn’t worth bothering with, and write instead about one of its inferior offerings whose ad campaigns are already burned into our retinas. Some people would argue I have a moral obligation to do this too, because, after all, muck like Kids is what everybody wants to see anyway. But given the self-serving prophecies that drive the movie business, how can anybody possibly tell what people want to see? For the past year I’ve been hearing that Pulp Fiction is some sort of grassroots, word-of-mouth sensation, but I’ve also been hearing that Miramax spent as much money advertising it as producing it. You can’t have it both ways: either the audience discovered it, or the audience got sucked in by the ad campaign (though one wonders whether it’s even possible for audiences today to discover anything that millions haven’t already been spent promoting).

Of course if making money is all that matters, then you can appear to have it both ways, because that’s the tried-and-true agenda of advertising: deception, lies, and bad faith. This helps explain why it’s convenient for the New York Times — which works hand in glove with Miramax in promoting many of its favorite goods, most of them antihumanist (like Kids and Woody Allen and Pulp Fiction), and trashing or ignoring some of its less favorite goods, most of them humanist (like The Glass Shield and Through the Olive Trees) — not to inform the public that it sponsors the Sundance film festival, so that when the Times offers “in-depth” coverage of Sundance every year it’s essentially promoting its own operation. That’s the Gingrichian alternative to arts funding — low-key (i.e., half-hidden) corporate sponsorship, which makes it impossible for us to determine what is and isn’t advertising, so that we’ll be fooled even more by the studios and their old-boy networks. Sundance, after all, is already known as the festival for Hollywood agents, designed to facilitate the selling out of American independents to the studios in a ski-resort setting (I’ve heard that cellular-phone conversations can sometimes be heard during screenings). So the festival allows the Times to affect a critical aloofness and at the same time keep its hands deep in the muck.

In any event, I can happily report that a year after Through the Olive Trees turned up at Cannes, a first feature by longtime Kiarostami assistant Jafar Panahi, The White Balloon, showed there and won the Camera d’Or. It’s been picked up by October Films, a small but ambitious distributor, and whether the Times reviewer likes it or not, it was so popular in Cannes it’s almost sure to get a commercial run in Chicago. Without being in any sense an imitation of Kiarostami, it has many related virtues. Unfolding in real time, it recounts the comic adventures of a seven-year-old girl in Tehran in the 85 minutes prior to the New Year’s Day festivities, and is easily as good a children’s movie as Babe.

Born in Tehran in 1940, Kiarostami trained in the graphic arts and worked designing posters, illustrating children’s books, making TV commercials (more than 150 between 1960 and 1969), and designing credit sequences for a few Iranian films before he was invited to set up a film unit at the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults in 1969, a state-supported arts and education organization started by the shah’s wife and now known as Kanun that has produced practically all of his films to date. The first film he made there — the delightful Bread and Alley (1970) — is a ten-minute narrative about a boy carrying a loaf of bread home through an alley and trying to get around an unfriendly stray dog. Shot without dialogue, the whole thing is deftly accompanied by Paul Desmond’s jazz version of the Beatles’ “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da,” and it already marks its director as a master of integrating landscape and action, as well as merging documentary and fiction. The same could be said for the subsequent Recess (1972), whereas the more experimental Two Solutions for One Problem and So Can I (both 1975) are remarkable conceptual miniatures that recall the imaginative freedom of early Jane Campion. (The first is a hilarious fictional essay about feuding schoolmates; the second, combining animation and live action, records the responses of two little boys to cartoon animals.)

I haven’t seen The Experience (1973), Kiarostami’s first feature, but it’s clear from the second and third, The Traveler (1974) and A Wedding Suit (1976), that his principal narrative mode from the outset is a kind of comic neorealism centered on little boys — a mode that continues in Where Is My Friend’s Home? (1987), the next Kiarostami feature I’ve seen, and beyond. Then come two documentaries, Homework and Close-Up (both 1990), and two fiction films, And Life Goes On… (1992) and Through the Olive Trees (1994). Close-Up and And Life Goes On… are most likely Kiarostami’s greatest films to date, but Homework and Through the Olive Trees are fascinating, accomplished forays in their own right. And they highlight the same strains found in the other two — “controlled” documentary with some of the techniques of fiction in a congested urban setting, and “open” fiction with some of the freedom of documentary in a lovely rural setting.

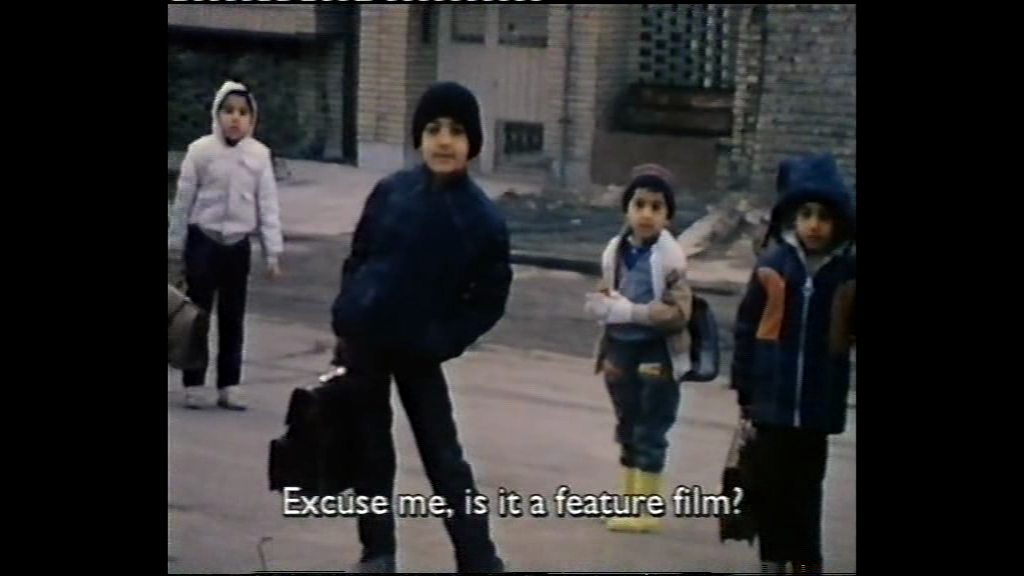

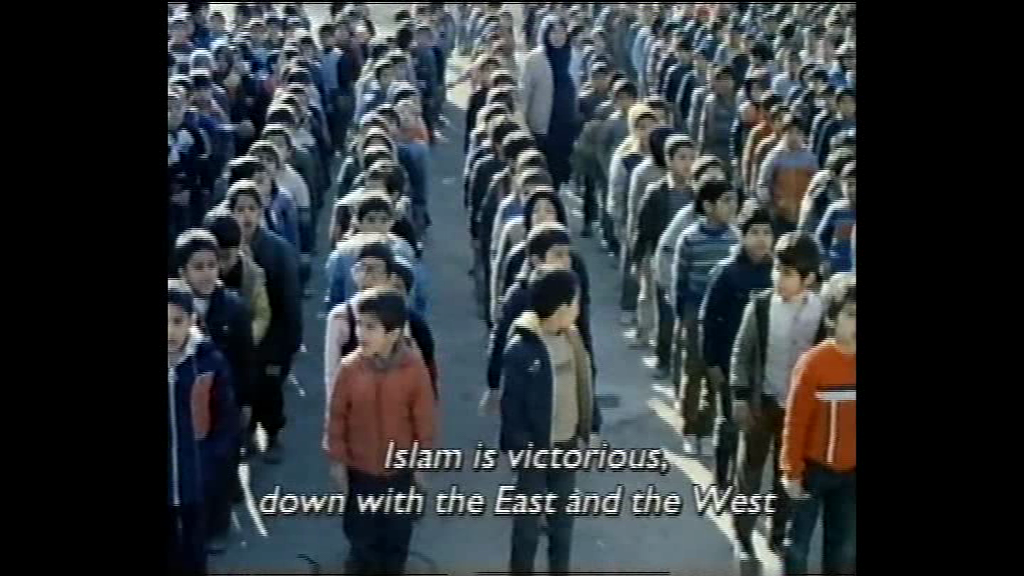

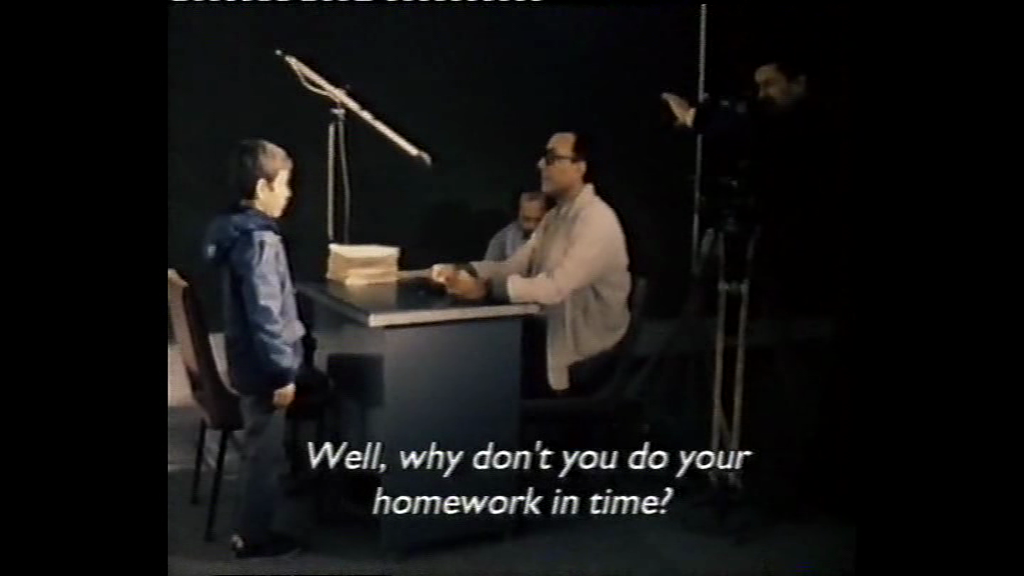

On the surface at least, Homework shows Kiarostami’s documentary methods at their simplest. (It’s the only one of his 16-millimeter features I’ve seen, though there are three others, one of which is also a documentary.) “It’s not a movie in the usual sense,” we hear him saying offscreen to another adult as we see several boys on their way to school. “It’s a research work. It’s a pictorial research on students’ homework.” He goes on to explain that he got the idea to do this while helping his own son with his homework, and shortly afterward we see the boys reciting elaborate religious chants while performing calisthenics outside in what looks like winter weather. (Because the sexes are segregated, no girls are in sight. In fact, we never see any females in the film; we only hear one woman later on, delivering expository narration about questionnaires sent by the filmmakers to the boys’ parents.)

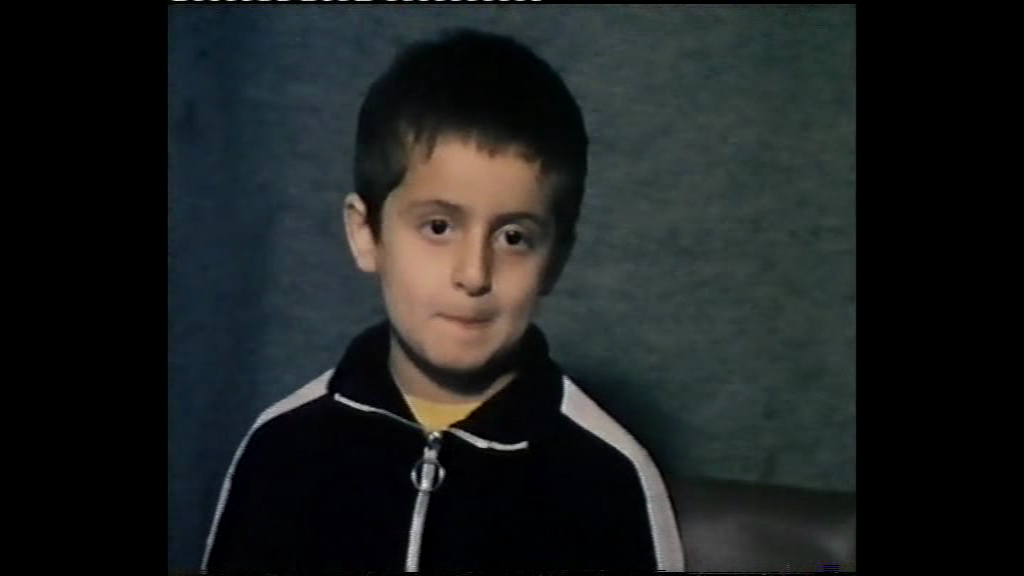

Then the movie settles down to its main bill of fare: interviews with a succession of grammar-school boys by Kiarostami himself about how they do their homework — whether their parents help, punish, or encourage them, whether they like doing it more or less than watching cartoons on TV, and so on. The most striking thing about these interviews is their formal presentation: the boys are filmed frontally, as in passport photos, and though Kiarostami is heard more often than seen, there are periodic cuts to the camera and cameraman supposedly filming the boys.

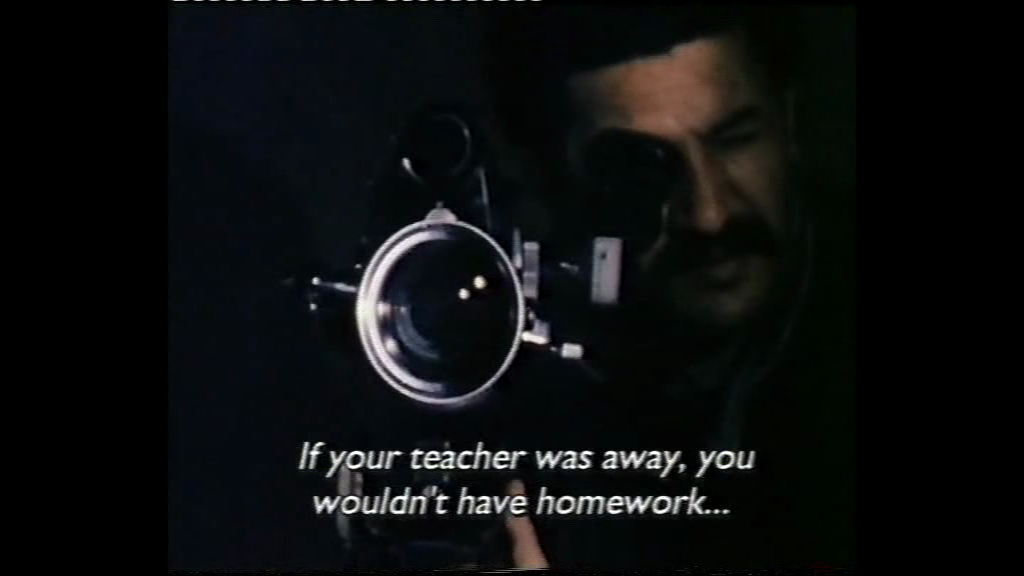

I say “supposedly” because there obviously has to be a second camera to film the first, and because we never see this second camera, these inserted shots are fictional: what we’re seeing is not what the boys are seeing at that moment, though the editing implies that it is. (In fact, Kiarostami has noted that he shot these inserts after the interviews, though he interspersed them with the shots of the boys as if they were occurring simultaneously.) This adds a layer of irony to Kiarostami’s remark in an interview about Homework that several boys lied to him about preferring their homework to cartoons, since Kiarostami’s documentary film rhetoric invariably entails a lie as well. Inadvertently or not, this becomes another way of saying that he doesn’t see himself as superior to the kids he’s filming; his attitude throughout seems anything but authoritarian. (The same attitude can be found at key moments in Godard’s interviews with children in his 1977-’78 TV series France/tour/détour/deux enfants, in which he asks a little girl about sound and music and a little boy about image in each episode. One key exchange I’ve always treasured is Godard asking, “Isn’t a shop window the same thing as a TV set?” and the little boy calmly replying, “No.”)

In telling contrast is the still ironic but clearly authentic celebration by Mohsen Makhmalbaf of his own authoritarianism and sadism while auditioning movie actors in his recent documentary Salaam Cinema, showing in the Film Center’s Iranian retrospective on October 21 and 22 — a film that should be read in part as Makhmalbaf’s reply to Kiarostami’s Close-Up, as a statement about the social status of cinema for ordinary people. Though it has been argued that Makhmalbaf’s interviews with eager hopefuls, laced with insults and humiliations, constitute a courageous exposé of his profession as well as himself, I found it much too glib about its “wisdom,” like Oliver Stone’s too-easy riffs on the media in Natural Born Killers. (The dialectical and at times symbiotic relationship between Kiarostami and Makhmalbaf, the two leading figures in Iranian cinema, is in some ways comparable to the relationship between Hou Hsiao-hsien and Edward Yang in Taiwanese cinema. Close-Up is a documentary about the trial of an impostor who pretended to be Makhmalbaf, and Kiarostami persuaded Makhmalbaf to let himself be filmed meeting the impostor at the end of the picture. Similarly, the capsule history of Iranian cinema via clips at the end of Makhmalbaf’s Once Upon a Time, Cinema concludes with an emblematic landscape shot from Kiarostami’s Where Is My Friend’s Home?)

Late in Homework there’s an even more ambiguous and ironic play with documentary film rhetoric than the inserts of the camera when the film returns to the boys’ extended Islamic chants and calisthenics outdoors. Offscreen the narrator, presumably Kiarostami, says, “In spite of all the attention of responsible people to arrange this ceremony properly, it was not performed correctly. So in order to show the proper reverence, we preferred to delete the sound from the filmstrip.” At this point the sound is abruptly turned off as the camera pans across the crowd of boys thumping their chests and declaiming, eventually arriving at the figure of the male teacher leading them in the foreground. It’s impossible for me to judge how sincere or hypocritical the pretext for this act of censorship is. But the effect is both analytical and aesthetic, displaying what amounts to a reverence for reality in its objectification of ritual that exists quite independent of any reverence (or subtle irreverence) for Islamic fundamentalist dogma.

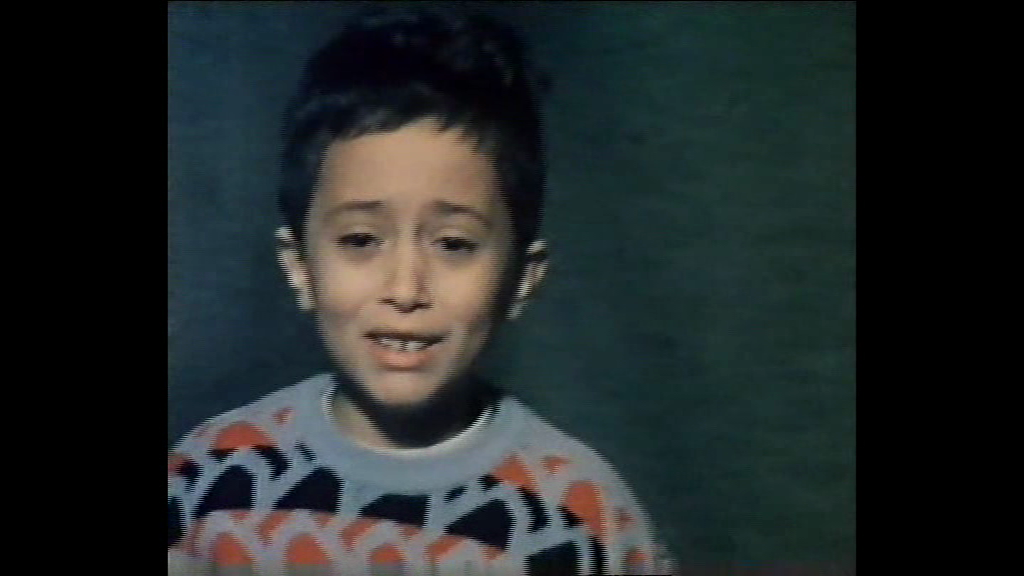

In short, it’s a moment of lyrical beauty as well as a moment of clarification, and the cinema of Kiarostami abounds in such moments. As simple and charming as most of Homework is, it winds up telling us a great deal about Iran in the 90s — everything from what some little boys think of Saddam Hussein in neighboring Iraq to what some Iranian parents think of education in America and Canada. (According to one father interviewed, homework is never assigned at American and Canadian schools.) There’s also the boy who cries during his interview, in part because he’s frightened of the filmmakers. (Kiarostami also reportedly filmed his own son, though it’s unclear whether he appears in the picture.)

Through the Olive Trees is usually described as the concluding feature in a trilogy, preceded by Where Is My Friend’s Home? and And Life Goes On…, but it’s important to note that each film was conceived and planned separately, and that Kiarostami has recently spoken about plans to make a fourth feature in the series. (The Chicago International Film Festival showed the trilogy in its entirety last fall.) In any event, you don’t need to have seen any of the preceding features for this one to register fully; the important thing to bear in mind is how organically, logically, yet unexpectedly Kiarostami’s oeuvre develops from one film to the next, each work containing the seed of its successor.

In fact, Where Is My Friend’s Home?, a comedy set in the mountain village of Koker in northern Iran, can be regarded as a kind of spin-off of Homework. The plot involves a poor schoolboy searching in a nearby village for the house of a friend who inadvertently walked off with his notebook containing all his homework. Three years after the release of that film a major earthquake devastated the region, and a few days later Kiarostami drove there with his son in an effort to find the child, a nonprofessional, who starred in that film; And Life Goes On… is a fictional re-creation of that journey, filmed in the same memorable landscape, again largely with nonprofessionals. Through the Olive Trees, which is again shot and set around Koker and again uses many nonprofessional actors, is either a fictional re-creation of an incident that occurred during the shooting of And Life Goes On… or an invented anecdote grounded in the real experience of shooting that film. I’m not sure which it is, but I’m not sure it matters.

Either way, the film affords Kiarostami yet another chance to reflect on the theme of Close-Up — the encounter between the world of cinema and the lives of ordinary people — without in any way repeating himself. After a young actor playing a newlywed husband keeps blowing his lines, in a hilarious extended sequence of fumbled takes worthy of Truffaut’s Day for Night, the director — Mohammad Ali Kershavarz, ostensibly playing himself but clearly standing in for Kiarostami — replaces him with an illiterate local mason who happens to be madly in love with the woman playing the wife, a young woman from a well-to-do family who refuses to speak to the mason in between takes. Most of the comedy is in the mason’s dogged, obsessive efforts to propose marriage to her despite her refusal to speak to him, and in the ambiguous roles played by the filmmakers and the film they’re shooting in this process. (One of the filmmakers is the assistant director — the only woman with an extended speaking part in either Homework or Through the Olive Trees.) In And Life Goes On… a filmmaker and his son learn something about surviving a disaster from ordinary people, and in this film ordinary people learn something about how to conduct their lives from filmmakers. (The director here serves as a kind of fatherly adviser to the mason.)

Once again Kiarostami’s use of the surrounding mountainous landscape is visually as well as dramatically breathtaking, culminating, as his previous film did, in an extended take that films the actors from such a vast distance it becomes a kind of comic and cosmic overview of the world — a vision that calls to mind that of Tati’s Playtime transposed to a rural setting. Like the brief suppression of the sound track toward the end of Homework, this shot reveals an almost mystical, open-ended sensibility that carries the film to a deeper, more mysterious level.

As beautiful, tender, funny, and profound as this vision is, it hinges on a calculation that seems less evident in the previous Kiarostami features I’ve seen — a calculation that seems to involve his international as well as his domestic audience. (There’s also an archness and cuteness that might be found in Where Is My Friend’s Home?, but not in Homework or any of the other Kiarostami features I’m familiar with.) Even the comic muteness of the heroine plays a role in this calculation, a ploy, perhaps, that circumvents the problem of how to deal honestly with women in a movie without offending the dictates of Islamic fundamentalism. It’s a knotty problem, and not one any of the Kiarostami pictures I’ve seen ever confronts directly. To get some measure of the sort of questions about women that Kiarostami’s films systematically avoid, you might want to turn to Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa’s 20-minute personal video essay A Tajik Woman, one of the prizewinners in the Festival of Illinois Film & Video Artists that’s showing Saturday night at Chicago Filmmakers, a program that conflicts with both of the Saturday Kiarostami screenings. But if you happen to see this video before seeing the Kiarostami films on Sunday, you’ll get a pretty comprehensive picture of what it means to be Iranian at the moment.