From the Chicago Reader (June 15, 1990).

Regarding Peter Biskind’s hyperbolic overestimation of Beatty, then and now — matched in a way by Beatty’s own jokey comparison of Biskind to Trotsky, as reported by Biskind in his recent and sometimes unwittingly hilarious Star: How Warren Beatty Seduced America (2010) — it seems that this has only grown over the past 20 or so years. In his Introduction, Biskind rhetorically asks, “how many defining motion pictures does a filmmaker have to make to be considered great?” and then rhetorically answers, “very few,” going on to assign only one or two each to Welles, Renoir, and Kazan, and just one to Peckinpah, but no less than five to Beatty, evidently regarding Bugsy as a towering achievement alongside such trifles as The Magnificent Ambersons, French Cancan, or Wild River. But this is the same writer who can call Kaleidoscope “James Bond lite,” allowing one to ponder what he might actually regard as James Bond heavy — or even as James Bond normal. — J.R.

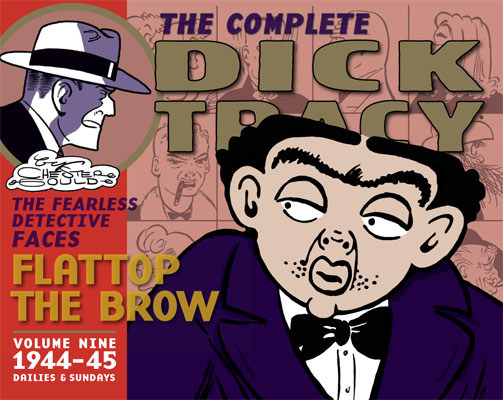

DICK TRACY ** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Warren Beatty

Written by Jim Cash and Jack Epps Jr.

With Warren Beatty, Charlie Korsmo, Glenne Headly, Madonna, Al Pacino, Dustin Hoffman, William Forsythe, and Charles Durning.

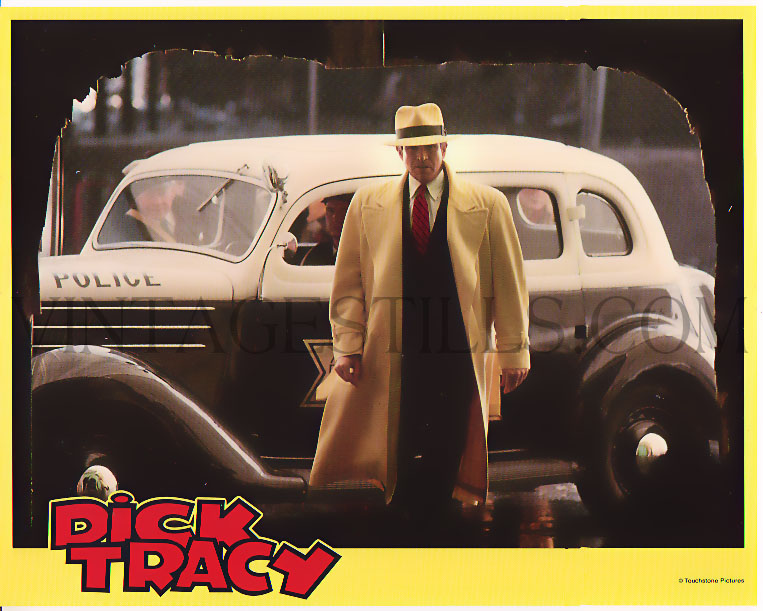

To its credit, Dick Tracy does succeed in capturing the precise look of a comic strip as no other movie before it has: the same unvarying primary colors; the same simplified characters, settings, and even props (like a big city newspaper called the Daily Paper and cars deprived of identifying insignia); and even some of the same oddball angles and setups, charmingly realized by cinematographer Vittorio Storaro and production designer Richard Sylbert. Better yet, the creepy world and characters of Chester Gould’s strip are reproduced with a rare fidelity to their spirit as well as to their distinguishing details. What the movie lacks, unfortunately, proves to be just as important: a feeling for action, an engaging story, an interesting and credible hero, and a vision to go with the look — a vision that would make the look functional, put it at the service of some higher meaning.

Ironically, most of these qualities — if not the look — are apparent in the strictly formulaic low-budget 1937 serial of the same title made for Republic Pictures (condensed into a feature as Dick Tracy, Detective). I suspect they’re also present in some form, however debased, in the low-budget Dick Tracy featurettes made for RKO in the mid-40s and in the TV series of 1950-’51. The advantage that these strictly unambitious programmers — as well as Gould’s original comic strip — have over the current release is that their principal (and honorable) mission is simply to hold an audience, not to be a major work of art or to rejuvenate the career of a fading box-office idol or to become a central preoccupation of Western culture. Consequently, one can simply take them or leave them without any elaborate song and dance. One doesn’t have to compare them to the work of Bertolt Brecht and G.W. Pabst, as Peter Biskind does with the new Dick Tracy in Premiere magazine, much less to Who Framed Roger Rabbit and Batman, the megahits of the last two summers.

Up to a point, it’s rather intriguing that Dick Tracy‘s settings seem so deliberately unreal; what’s less intriguing is that they barely seem thought through — or thought about — at all. Once you acknowledge that the look of the comic strip has been caught, you begin to wonder why it has been caught. What is it saying about the late 30s or early 40s (when the action appears to be set) or the late 80s and early 90s — insofar as it’s saying anything at all? The answer appears to be: as little as possible. In other words, Dick Tracy is by design an artfully constructed nullity, attractive and charming in many spots but pretty close to empty.

***

By and large, with a few notable exceptions, Warren Beatty has shown an unusual talent for playing by the rules of mainstream Hollywood while somehow conveying the impression that he’s a radical innovator. It’s a duplicity that has worked wonders with some films, those directed and mostly written by others, such as Lilith, Bonnie and Clyde, McCabe and Mrs. Miller, Shampoo, and Ishtar, but in the cases of his two previous directorial forays — Heaven Can Wait (which he codirected with Buck Henry) and Reds — the results are a good bit more ambiguous.

Heaven Can Wait (1978) was a well crafted and charming if unadventurous comedy that improved on its source (Here Comes Mr. Jordan of 1941), but didn’t come within even remote hailing distance of the sublime Ernst Lubitsch masterpiece of 1943 that it had the nerve to steal its title from. As for Reds, I blush to admit that nine years ago I was sufficiently impressed with what seemed to be its political, historical, and formal audacities to overlook all the gloppy Selznick-like trappings that enveloped them and ultimately became part of their meanings. The fact that Beatty had produced, directed, and cowritten an old-fashioned romantic blockbuster about American communists (John Reed and Louise Bryant), coupled with his brilliant idea of dialectically interweaving the testimonies of their real-life contemporaries, encouraged me to minimize the misogynous trivialization of Bryant’s part in the story as well as the movie’s own built-in destiny — it was shown personally by Beatty to the Reagans in the White House and received a dozen Oscar nominations (two achievements that indicate just how audacious the picture really was).

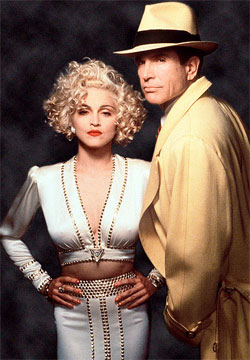

In the case of Dick Tracy, Beatty’s warring impulses seem downright schizophrenic. The movie opts for ultrasimplicity as if this were in itself a high-art position and then lands the viewer in the clutter and confusion of an average music video. It offers Madonna in all her splendor, dressing her in black and white clothes so tight that she resembles Jessica Rabbit stretched out on a torture rack. It gives her original songs by Stephen Sondheim, and then brutally crosscuts between these songs and other events until they and she get lost in the jumble.

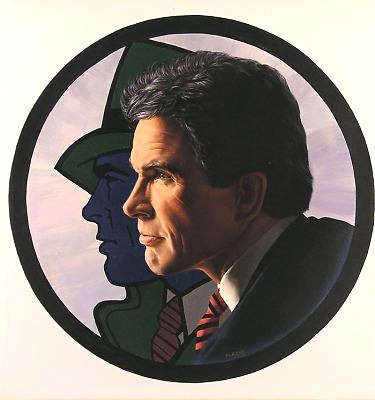

Beatty has never shown much talent for acrobatics, and this movie has him (or his doubles) scaling buildings, leaping through skylights, and sliding down a lamppost — just like Batman but without any grace. He’s also made the object of unquestioning adoration for the two leading ladies (Madonna’s Breathless Mahoney and Glenne Headly’s Tess Trueheart) and an orphan called Kid (Charlie Korsmo), for no apparent reason other than his professional dedication and good looks. Madonna and Korsmo both have charisma and acting skills to spare, while Headly is passable in an underscripted part, but Beatty’s enactment of Tracy as a square goody two-shoes, though perhaps true to the strip, leaves a dead space on the screen. Beatty intensifies the problem by according him a number of extended close-ups and making him tongue-tied as well — not a Tracy trait, but one that puts him more in line with other Beatty heroes. It doesn’t make him any more charming, and combined with the excessive use of close-ups, it even becomes at times a kind of hectoring rhetorical effect, as if Beatty is pounding on a door that refuses to open.

It’s important to bear in mind that Tracy’s importance in the strip was mainly graphic, a series of straight lines and sharp angles that contrasted with the roundness of the other characters. This contrast had a symbolic importance vis-à-vis Tracy’s incorruptibility, but Beatty’s features convey no such impression, so the difference is lost in the movie. What’s retained is the sense that the law is suave and attractive while criminals are hideously ugly, although even here there are no other particularly suave or attractive people working at the police station. (Maybe that’s why Tess and Breathless are both so smitten; Dick’s the only hunk in sight.)

As I said, Beatty has been unusually good at working both sides of the street — distancing himself from his more conventional Hollywood image while continuing to milk that image for everything it’s worth. One sentence about him in the Dick Tracy publicity materials conveys this double standard perfectly: “Warren Beatty has been a ‘movie star’ since he appeared in his first film, Splendor in the Grass, in 1961.” Putting quotes around “movie star” while retaining the phrase and its full meaning represents an attitude that’s highly characteristic of Beatty’s career and self-image. It matches his “agreement” in 1982 to act in any feature written and directed by Orson Welles, for $2 million and 10 percent of the profits — which would get the film made — but only if he could produce it and have final cut. (Maybe he was fearful of Welles’s frequent dictum to actors: “If your performance isn’t any better, I’ll have to give you some close-ups.”)

On the one hand, Beatty has had the initiative and good sense to use Elaine May’s considerable writing talent memorably on several of his pictures — with credit on Heaven Can Wait and Ishtar, and without it on Reds and Dick Tracy. (It seems probable that some of the goofy free-form monologues of Al Pacino’s Big Boy Caprice in the latter are her work. Sample: “‘A man without a plan is not a man’ — Nietzsche.”) Other uncredited writers who have reportedly contributed to the Dick Tracy script include Beatty himself, Bo Goldman, Floyd Mutrux, and Robert Towne. On the other hand, Beatty made the rather odd decision to produce James Toback’s unmemorable The Pick-up Artist (1987) anonymously — that is, serving as “producer” rather than producer. Like Gould’s Tracy, you might say that with Beatty, profile is everything, while substance is, if not nothing, at least second fiddle.

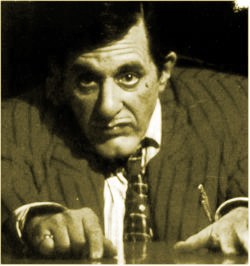

Some of his stylistic sources in Dick Tracy show a certain amount of discernment. The candy-colored clothes and the highly artificial cityscapes occasionally call to mind Joseph Mankiewicz’s underrated film version of Guys and Dolls, while the overall portrait of Pacino’s Big Boy, the head hoodlum — arguably the best thing in the movie — may owe a few details to Rico Angelo (Lee J. Cobb) in Nicholas Ray’s Party Girl, a film whose color schemes might have given Beatty some ideas as well. (Guys and Dolls was set in a fantasy Manhattan, Party Girl in a fancifully remembered 20s Chicago; Dick Tracy is set in a nonspecific city in the 30s or 40s, although it seems closer to Chicago than to Manhattan.) Unfortunately, the mise en scène and story-telling talents of both Mankiewicz and Ray go well beyond Beatty’s range, and when it comes to the business of directing and editing, a more likely working model might have been Francis Coppola’s The Cotton Club, which made a similarly flashy stab at emulating Hollywood montage sequences of the 30s; it also hacked musical numbers into very unmusical music-video mosaics, and sought to depict its criminal characters as a band of colorful, violent lugs.

(The above list of potential sources refers only to Beatty; Pacino’s sources for the hunchbacked Big Boy are said to be his own earlier stage performances of Brecht’s Arturo Ui and Shakespeare’s Richard III — although, having suffered through about half of the latter, I must say that Pacino seems to have gained a sense of humor about it in the interim. Dustin Hoffman’s almost-as-funny Mumbles is said to be modeled after the Hollywood producer Robert Evans.)

A personal story — Tracy caught between libido and love, romance and duty, work and family, parenthood and freedom — is at the center of the film, along with a style that seems designed to suggest the innocence and simplicity of Beatty’s view of the world as a child. But this doesn’t match up very well with the mechanically crosscut chunks of movie that are supposed to fulfill expectations of Tracy as a crimebuster, or with the various action sequences, which Beatty never treats more than cursorily; even a big plot surprise in the penultimate scene comes across as going through the motions.

Despite various echoes of Who Framed Roger Rabbit and Batman, Beatty studiously avoids the high-tech feeling of other recent movie blockbusters; Tracy’s wristwatch radio functions in the plot and as a running gag, but it conveys no technological glamour. The movie’s dreamy, seminostalgic evocations of the late 30s and early 40s may in fact be its most commercially daring aspect insofar as they refuse to cater to the tastes and demands of contemporary teenagers. (Indeed, it’s been reported that during various test previews, some teenagers have expressed anger and outrage at Madonna’s attraction to the 53-year-old star, which is even acknowledged at one point in her dialogue: “What I’m looking for is a driver, preferably with some mileage.”)

I have to admit that my own expectations for the film were pretty high, so my disappointment may be disproportionate. A second look may reveal virtues I’ve failed to notice. It’s certainly to Beatty’s credit that the movie looks like nothing else around, and that the hammy work of Pacino is the best thing of its kind since Jack Nicholson in Batman — two forms of mannerism that may not be quite a style, but that are certainly pleasurable in any case. But without an interesting hero or story, they seem to have nowhere to go. Whether this should be blamed on corporate pressures or Beatty’s uncertainties or both is not entirely clear, although it’s hard to believe that the Disney people forced those querulous close-ups on him. It’s almost as if the movie were hovering around the anxiety of a mid-life crisis without ever quite owning up to it — circling evasively around an obsession that stands between Beatty and the movie he presumably wanted to make.