This originally appeared in the August 15, 2003 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

The Gatekeeper — produced, directed, and written by someone you’ve never heard of, with a cast that’s equally unknown — is a realistic, no-nonsense independent feature about Mexican immigrants enslaved just after crossing illegally into the U.S. Masked and Anonymous — a Bob Dylan vehicle packed with stars, directed by a sitcom veteran, and produced by the BBC — is a fantasy about a legendary singer giving a benefit concert for wounded counterrevolutionaries in a slum-infested city where the country’s dictator is dying.

These movies have little in common, apart from being grim commentaries on the corruptions of the American dream that use impoverished southern California locations. Yet I had the same sensation after seeing each of them: I felt I’d just received a jolt of contemporary reality, something I rarely can say about commercial movies nowadays.

Even if only indirectly, both movies have something to say about global warming and the depletion of the ozone layer, government and crime, the torrents of spam flooding e-mail accounts, the relentless aggression of telemarketing, the political chaos in Iraq and other places (including California), the misery of the poor and homeless, and the almost random casualties arising from heat-crazed and trigger-happy cops and soldiers surrounded by people who despise them. When thunder and rain hit the sordid exteriors of Masked and Anonymous, this registers less as bad weather than Old Testament retribution. And when an American exploiter of terrified Mexicans in The Gatekeeper casually rapes one of his employee-slaves, it seems like business as usual.

In one way or another, business as usual is what these two movies are fundamentally about, and I’m tempted to think that some of my colleagues who hate Masked and Anonymous are responding to it more as a class statement than as an aesthetic offense. After all, Woody Allen, Mike Figgis, and Oliver Stone have made movies that are just as muddled, but because they chose ritzier settings, they tend to get the benefit of the doubt. I would argue that the grungier Masked and Anonymous and The Gatekeeper present more of an existential challenge, tacitly suggesting, “So this is what you’re willing to put up with?”

The Gatekeeper, with its 70s-exploitation-picture look and its refusal to make any detours into comedy or atmosphere, has an unvarnished clarity. By contrast, Masked and Anonymous is borderline incoherent in spots, and it’s certainly mannerist: nearly all of the characters talk the same way, just as they would in a William Faulkner novel or a Joseph L. Mankiewicz chat fest like The Barefoot Contessa — only in this case they all talk like Bob Dylan. Neither feature qualifies as what we’d commonly label “professional” filmmaking, but even though Masked and Anonymous gets metaphysical and The Gatekeeper milks suspense as routinely as any B thriller, the absence of polish enhances my sense of the reality in them.

Bits of reality in movies — spaces, durations, characters, events, settings, thoughts, moods, feelings — vary as much as our everyday experiences. We usually don’t admit to going to movies in search of them because so many of our cultural commissars keep insisting that we go mainly in search of escape, though sometimes those who do go for escape complain if a film isn’t sufficiently realistic. I assume we go to movies for all sorts of reasons, and among them is learning or rediscovering something real about our lives.

Global warming and the depletion of the ozone layer have barely been acknowledged in our movies, and to find speculation about their effect on the future we have to turn to science fiction — A.I. is the most recent example that springs to mind. Other films offer different lessons. In American Splendor — a crazy quilt of fiction and documentary about Harvey Pekar, a sour, working-class comic-book writer living in Cleveland — we get some piercing insights into what makes Pekar first acceptable and then unacceptable on David Letterman’s TV show, which is a far from trivial matter. And we learn about ordinary Mexican-American family life in Spy Kids 3-D: Game Over, even though most of the movie takes place inside a video game.

Sometimes characters, dialogue, or situations ring false in movies, yet the apparent impulse behind their creation rings true. My enthusiasm for Down With Love has little to do with its period agenda and much to do with what it says about the present — an apparently inadvertent statement arising out of multiple misunderstandings (as well as a genuine appreciation) of the past. All that the movie gets wrong as well as right about the 50s and 60s allows it to express a contemporary yearning for innocence that’s far more poignant and telling than any period re-creation. That the movie seems to address the present only by accident makes its truth more persuasive — it has the authenticity of a Freudian slip.

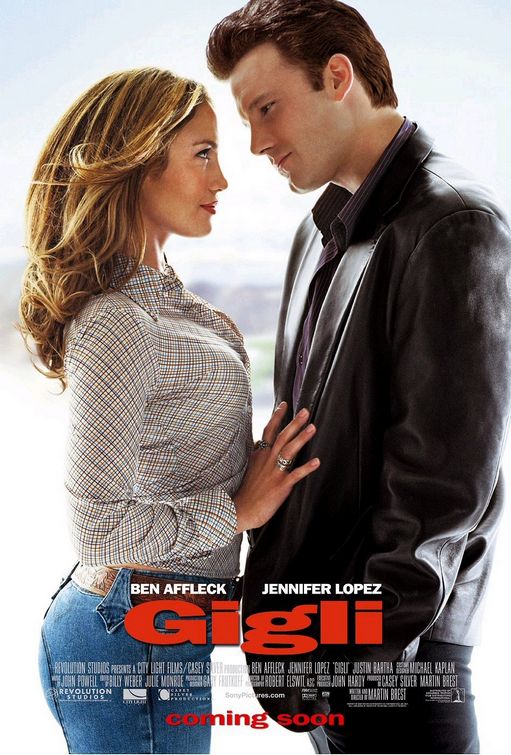

In Gigli Jennifer Lopez, playing a hit woman for the mob, gives Ben Affleck, an only slightly less ridiculous employee of the same mob, an outlandish lecture on the innate superiority of the vagina to the penis after he’s explained to her why he’s sure the penis is better. She delivers this speech while doing exercises on the floor of the suite they’re sharing, and we can readily accept the floor and the exercises as real even if we can’t accept that her character is. (That she’s an avowed lesbian and Affleck’s character is straight is an additional factor in the scene’s dynamics, and credibility may be further strained because we know these actors are a real-life couple.) It is of course utterly preposterous to place the vagina and penis in competition — a reductio ad absurdum of the American obsession with seeing everything in competitive terms, whether it’s businesses, sports teams, political parties, Time and Newsweek, McDonald’s and Burger King, races, or countries. Nonetheless I think something real is going on in this scene, and it probably has something to do with Lopez’s pleasure in her own narcissism and my pleasure in observing it, combined with the small frisson that comes from seeing a burst of neofeminist pride smuggled into this movie.

Amy Dawes writes in her review of Gigli in the August 4-10 Variety, “Solid tech contributions work toward a realistic feel.” Which implies that less technical polish might have impeded the overall credibility — the precise reverse of what, for me, adds to the realistic effect of The Gatekeeper and Masked and Anonymous. She’s writing for the trade, so does this judgment reflect the business-as-usual thinking — that is, the more money you spend the more real your films are? Or could she merely be trying to rationalize the pleasure she takes in the movie in a way Variety would find acceptable?

I’ve deliberately refrained from citing the names of the directors and writers of these pictures because I don’t think auteurism gets us very far toward understanding or appreciating what’s real in them — apart from the fact that the writer-directors of Spy Kids 3-D and The Gatekeeper are Mexican-American. And in filmmaking intentionality tends to be murky — especially when decisions are made collectively, which is most of the time. This was also true decades ago, though the relatively hidden Hollywood struggles of people like Orson Welles and Nicholas Ray deserved to be better known at the time. Today we understand that “a film by Martin Scorsese” is also partly “a film by Harvey Weinstein.”

I’m inclined to credit Dylan for some of the reality as well as some of the fantasy in Masked and Anonymous. But, as my Gigli example suggests, no two observers are likely to see reality and fantasy in a movie the same way. Many reviewers have focused on the reality or fantasy of the Dylanology rather than on the reality or fantasy of the way America and business are portrayed, and considering how much Dylan’s songs and monologues dominate the sound track — even when they contradict the narrative placement of his character in the story — they have a point.

When I attended a film festival in Bologna several weeks ago, I was particularly looking forward to a retrospective devoted to early CinemaScope and to seeing The Robe, the first CinemaScope film, for the first time since I was ten. I remembered it as a piece of spectacular religious kitsch, though it’s somewhat better than that. What neither I nor any other ordinary viewer realized in 1953 is that it was written chiefly by a member of the Hollywood Ten, Albert Maltz, who received no screen credit at the time because he’d been blacklisted. Maltz’s name was recently added to the credits by 20th Century-Fox as an act of belated reparation: it’s on the DVD of The Robe, though there’s no acknowledgment of its ever having been omitted.

I didn’t know what the Hollywood Ten was in 1953. I also didn’t know that the film’s adaptation of the Lloyd C. Douglas novel — about a Roman centurion who oversees Jesus’s crucifixion, wins his robe in a gambling game at the foot of the cross, has a religious awakening, and becomes a Christian — was a clear allegory about the blacklist. At one point the Roman emperor, angrily rounding up Christians in hiding, says to his lackeys, “I want names!” The film might even be called Communist propaganda, especially by people with a cold war mind-set — a primary source of this country’s competitive hang-ups — who assume that any anti-anti-Communist statement automatically qualifies as communist.

It would be nice to think that Maltz was offering audiences in 1953 a jolt of reality in a conventionally pious spectacle, but I’m not convinced he was. Judging from my own reaction back then, Nicholas Ray’s western Johnny Guitar — another antiblacklist allegory, released the following year by Republic Pictures, a much more modest studio than Fox — came closer to jolting us with a lynching that was the consequence of a twisted code of justice. (A teenage boy is pressured by a hysterical mob into betraying an adult friend; he’s been promised clemency, but gets hung anyway.) But the contemporary parallel was buried under western conventions — as it was in the 1952 High Noon, a less morally attractive blacklist allegory — that severely limited its power to speak to its original audience. For similar reasons, a pro-blacklist allegory like On the Waterfront might have been equally ineffectual as propaganda.

It’s relatively easy to ferret out these buried social references today — along with personal references, such as Cary Grant’s character in Bringing Up Baby, including his thick glasses, being modeled on John Ford (who’d recently been Katharine Hepburn’s lover) and the villain played by Raymond Burr in Rear Window constituting Alfred Hitchcock’s belated revenge against David O. Selznick. Are there just as many bitter almonds hidden in today’s movies, waiting to be uncovered by future generations? Or was this sort of subterfuge a phenomenon made possible by the relative stability of the old studio system?

To answer this question adequately, we first have to determine what the social and political taboos are that govern commercial moviemaking today. But are we in a position to know? Audiences seem to believe that movies are no longer censored, at least not as they once were — which is precisely what gives the suppressions that do exist a power they never had before. And once we lose awareness that omissions are being made, we also lose an awareness of the reality of what’s being omitted.

The industry rationalization for suppressing realities, I suppose, would be that people don’t want to see anything in a movie that might make them unhappy — an argument that could theoretically rule out just about anything. (During the more puritanical 50s it seemed at times that certain things were inadmissible simply because they might give some people joy.) I suspect we have less of a grasp of what’s being held from our view than our counterparts did half a century ago, and I sometimes wonder if we’re even equipped to figure out what we want and need. Maybe that’s why the few jolts of reality I can get from Masked and Anonymous, The Gatekeeper, American Splendor, and even Gigli seem so important.