From the June 11, 1999 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

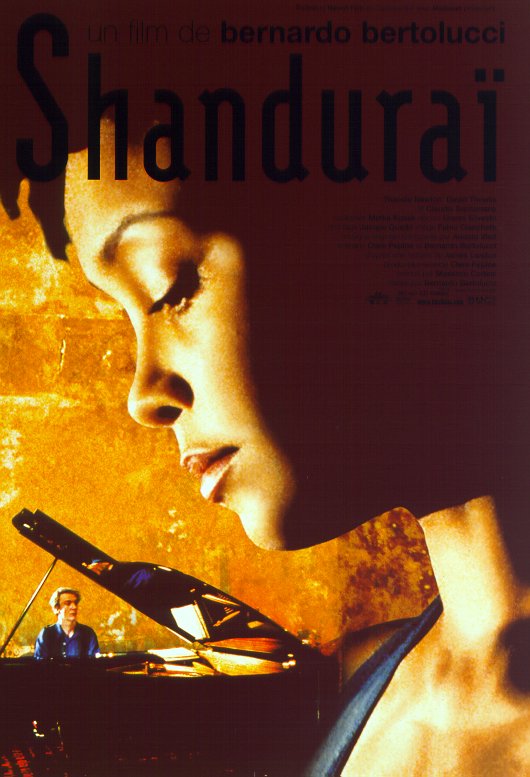

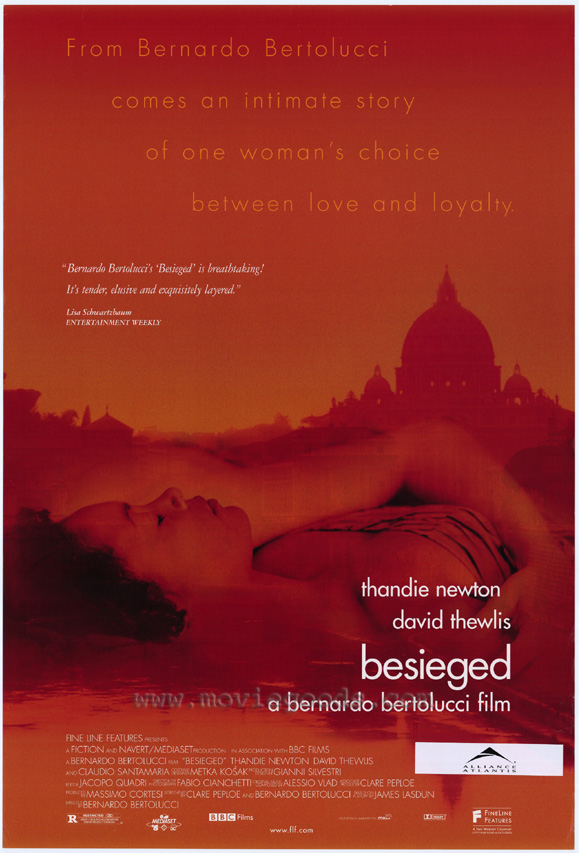

Besieged

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by Bernardo Bertolucci

Written by Bertolucci and Clare Peploe

With Thandie Newton, David Thewlis, and Claudio Santamaria.

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

Many times over the past three decades I’ve been close to giving up on Bernardo Bertolucci. The rapturous lift of his second feature, Before the Revolution (1964), promised more than he seemed prepared to deliver with the eclectic Partner (1968). Yet it was The Spider’s Stratagem (1970) rather than The Conformist (made just afterward and released the same year) that renewed my faith in his talent. Both movies, like Before the Revolution and Partner, were the flamboyant expressions of a guilt-ridden leftist, a spoiled rich kid with a baroque imagination and a social conscience that yielded dark and decadent ideas about privilege and guiltless fancies about sex. Where they differed for me was in the degree to which The Conformist succumbed to fashionable embroidery, a stylishness that took the place of style.

It was the relatively big budget The Conformist, an adaptation of an Alberto Moravia novel, that made Bertolucci’s name in the world market and so influenced American movies that Coppola’s Godfather trilogy would have been inconceivable without it. But it was the more ponderous and adventurous The Spider’s Stratagem — a TV commission adapted from a Jorge Luis Borges story, “Theme of the Traitor and Hero” — that showed Bertolucci truly grappling with his material and not merely with his markets. His mise en scène may have overwhelmed his content, marking him as a mannerist, but there was nothing glib about that content, and the mise en scène was more than just decorative. But both elements were too European to capture the American market — unlike the glossier The Conformist, so decorous it suggested one of Marshall Field’s window displays.

So when Last Tango in Paris emerged as the next Bertolucci feature, catapulting his reputation into the stratosphere, it was clear that, for better and for worse, he’d found his overall commercial direction. Then his daring project to adapt Dashiell Hammett’s communist novel Red Harvest fell by the wayside, to be replaced by the star-driven blockbuster 1900 — an attempt to mount a Marxist historical pageant on the scale of Gone With the Wind that wound up dissatisfying just about everyone (including Bertolucci, after 72 minutes were chopped from his English-language version). Next came the less prestigious but arguably more interesting Luna (1979) and The Tragedy of a Ridiculous Man (1981), followed by The Last Emperor (1987), which signaled a new commercial configuration characterized by Bertolucci’s determination to make films only in English, regardless of setting or subject matter; in the 90s this yielded The Sheltering Sky, Little Buddha (which was also recut for the U.S.), and Stealing Beauty.

For me the best of these was The Last Emperor — if only because it suggested a temporary resolution to the uneasy competition between Marx and Freud that had dogged Bertolucci’s work from the beginning — and the worst was Little Buddha, a film that floundered conceptually and sprang to life only momentarily, approximating the magic of a fairy tale. But all three confirmed that Bertolucci was no longer a mannerist with a manner, or even a culture, he could call his own. Even Stealing Beauty, which represented his return to Italy after over a decade of wandering the globe, seemed a good deal more tentative and cautious than any of his exciting early work; I liked it more than many of my colleagues did but concluded that Bertolucci was still feeling his way back to his stylistic roots.

Besieged — like The Spider’s Stratagem, a small-scale TV commission — marks Bertolucci’s triumphant return to those roots. Admittedly, it adheres to the use of English that characterizes his last four features and lacks the intellectual ambitions of his first four. Moreover, its plot, adapted from a story by James Lasdun that I haven’t been able to track down, is both slight and somewhat obvious. But as a piece of cinema, it’s the most pleasurable new movie to arrive in Chicago this year, more sensual than Last Tango in Paris and more stylistically engaging than anything he’s done since The Spider’s Stratagem. I first encountered Besieged last year at the Toronto film festival (where it was titled The Siege); since then I’ve returned to it twice with a great deal of enjoyment, and I look forward to seeing it again, much as I would return to a favorite piece of music.

To call a movie a masterpiece when its subject matter is slight raises the issue of whether the metaphysical notion of “pure style” — that is, style divorced from content — is defensible or even imaginable. I don’t think it is, but in the case of Besieged the subject is slight only in the sense of being intellectually and politically undeveloped, not in the sense of being stupid or apolitical. The movie’s true focus as well as its distinction lies in moment-to-moment experience rather than in thematic overview, and Bertolucci’s attentiveness toward and fidelity to that experience is precisely what unleashes his style. Most of this transpires without dialogue, through camera movement and editing, coordinating a powerful sense of place with the capacities of two very skillful actors, utilizing selective splashes of color to render stabs of emotion, and using pieces of music that range from classical piano to African pop to chart the shape, mood, and rhythm of separate sequences.

Though one obviously can’t and shouldn’t ignore the movie’s theme, what that theme consists of is whatever Bertolucci needs to capture the moment-to-moment experiences he’s interested in, and not much more. (As Dave Kehr wrote in Film Comment, “Where Bertolucci’s characters were once united by their unexpressed desire to return to the warmth and security of childhood, to the love of a mother and the safety of a womb, they now define themselves by their denial of the past and their passionate embrace of the present.”)

And what is that theme? The mutual seduction of an African woman named Shandurai (Thandie Newton) and an English classical pianist named Jason Kinsky (David Thewlis) in a Roman villa only a stone’s throw from the Spanish Steps. How this comes about is the sum of the movie’s concerns, and readers should skip the remainder of this section if they don’t want to know any more of the plot. Shandurai, a medical student, works as the pianist’s housekeeper, having recently fled Africa after her husband, a schoolteacher in her unidentified native country, was thrown into a military prison for ridiculing the dictator in power. The seduction begins when Kinsky — a recluse who inherited the villa and its many artworks from his aunt and who gives occasional piano lessons to children — suddenly and awkwardly blurts out that he loves her and would do anything in his power to make her love him. Shocked and terrified, Shandurai screams back that he can get her husband out of jail — which proves to be the first indication Kinsky’s had that she’s married.

Nothing more on the subject is said by either of them. But as time passes and Shandurai sees the villa’s various artworks — paintings, sculptures, and tapestries — gradually disappear, she comes to realize that Kinsky is responding literally to her impulsive challenge. After he sells his piano and she gets word that her husband, freed from prison, will join her in the morning, she gets drunk on the bottle of champagne she’s bought for the occasion, tries to write a simple thank-you letter to Kinsky, concludes before the night is over that she loves him, and proceeds to his bedroom. After a night of drinking on his own, Kinsky is fully dressed but fast asleep; Shandurai undresses him and lies down beside him. In the early dawn, when her husband rings the doorbell downstairs, she hesitates, then gets out of Kinsky’s bed to greet her husband, and the movie ends.

If Besieged were a piece of music, it would be easier to defend; one could simply fall back on the wisdom of Duke Ellington when he said, “If it sounds good, it is good.” But even though Besieged is mainly structured in visually appealing ways around pieces of music that sound good, it can’t be justified that simply, especially now that some colleagues of mine (all of them white Americans) have been calling it racist and colonialist. I don’t agree with either of these charges, but they deserve some response, particularly because they suggest some interesting differences in cultural conditioning and positioning, in relation to history as well as geography.

Let me begin with the first chorus of the only song in Spanish I’ve ever known by heart, the Mexican folk song “La llorona” (“The Weeping Woman”), first in Spanish and then in English translation:

Todos me dicen el negro, llorona,

Negro pero carinoso. (repeat)

Yo soy como el chile verde, llorona,

Picante pero sabroso. (repeat)

They all call me the black man, weeping lady,

Black but affectionate.

I am like the green chile, weeping lady,

Spicy but delicious [or “tasty”].

I’ve remembered this song all three times I’ve seen Bertolucci’s movie and responded to its erotic treatment of Newton, the English actress who plays Shandurai and embodies the film’s central consciousness. (Born to a Zimbabwean mother and a British father, Newton lived in Zambia until she was three, when her family moved to England; at 18 she made her screen debut in the Australian feature Flirting, which she dominated almost as much as she dominates Besieged. All the pieces of African pop music used in the film are her selections.) My association of the film with “La llorona” arose partly because I misunderstood el negro to mean “black woman” instead of “black man,” until a Latino friend recently corrected me, but this error changes none of the song’s relevance. I would argue, in fact, that Besieged is racist in the same way and to the same degree that “La llorona” is — to my mind, not at all, at least in the context in which I came to understand it. I learned “La llorona” from folksinger Guy Carawan at Highlander Folk School — a coed, interracial civil rights camp staffed in part by former freedom riders — during the summer of 1961, at the same time that I and my fellow campers learned “We Shall Overcome,” which we sang only slightly more often. This was long before notions of racial separatism became prominent in the civil rights movement and even longer before puritanical notions of political correctness began to wipe out the permissibility of such sentiments. As best as I can recall, no one at Highlander in 1961 objected to this song in any way.

I suspect that if Shandurai didn’t arrive at the conclusion — however drunken or momentary — that she loved Kinsky, the charges of racism and colonialism would have been less likely. One might even argue that, though it’s highly productive as the wet dream of a guilty white Italian male filmmaker (more productive, to my taste, than the racial and colonial conceits of a Star Wars movie), the plot isn’t very believable. Shandurai’s fluency in at least three languages and her status as an A student in med school, combined with her strenuous housekeeping chores, is theoretically possible, yet at times it seems nervously overdetermined — rather like making Sidney Poitier the equivalent of a Nobel Prize-winning doctor in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? Kinsky’s virtual self-obliteration in the service of his passion is similarly possible but also difficult to grasp when we know practically nothing else about him. Even if we decide that the movie is an allegory, requiring types rather than fleshed-out characters, one might easily object that casting an actress whose skin color is cafe au lait to stand in for black Africa is tantamount to cheating.

This is why I insist on calling the story (which functions formally like a libretto) slight and why another colleague understandably calls the movie a piece of fluff — the same sort of fluff that apparently became a hairball for my more puritanically inclined colleagues. But that doesn’t mean Bertolucci would have made a better movie if he’d cast a blacker actress than Newton to play Shandurai, made her character less of an overachiever, or provided Kinsky with more of a back story. What this movie is about is the particular interaction of this fluff, these actors, this house, this set of musical pieces, and the stylistic invention of this director. To impose any other set of coordinates on such a story is to reject what they produce together, to dazzling effect.

Significantly, given the film’s confined and well-defined sense of terrain, every scene set in Africa occurs in one of Shandurai’s dreams, though the first of these scenes, which opens the film, is identified as a dream only in retrospect, when she’s awakened by rumbling sounds from her maid’s room in the villa. (The scene passes from a griot — an African storyteller-musician — to the hospital where Shandurai works to the schoolroom where her husband is arrested and concludes with the reappearance of the griot; like most of the film, it’s an adroit blend of objective exposition and Shandurai’s subjective impressions.) After she gets out of bed and starts to look for the source of the rumbles — a brief passage punctuated by jump cuts to convey her fragmented waking consciousness — she discovers it’s the sound of a dumbwaiter, which she’s been using as a cupboard, being lowered from a higher floor. Opening the cabinet, she finds a sheet of blank music paper with a question mark drawn on it.

The next sequence shows us Kinsky waking in the morning upstairs when his alarm goes off, getting into a robe, and walking to a window just in time to see Shandurai passing on the cobblestone street below, en route to the subway. After examining a patient with other medical students, she arrives home while Kinsky is playing his grand piano upstairs and starts to do her housework, dusting the sculptures, making his bed, and collecting his shoes (and catching a glimpse of Kinsky passing as she snags one of the shoes from under the bed).

Practically all of the film unfolds in this fashion, with a minimum of dialogue, a great deal of play on glances and gestures, and fleeting impressions of sounds as well as images. Apart from re-creating the evocative syntax of silent cinema even more effectively than The Thin Red Line — especially when solo piano pieces, most of them performed by Kinsky, serve as traditional silent-movie accompaniments — the pleasures of the film’s style largely consist of the artful mosaic patterns created by the arrangement of passing details. Or, to describe it in musical terms, the melodies created by linking various notations as if they were tones, yielding playful rhymes (cutting from a dark pink orchid to an umbrella of the same color, or from a flow of beer to a wash of soap suds) as well as reprises (two 180-degree camera tilts that frame a dream Shandurai has as she sits at her kitchen table).

As I’ve already suggested, the limitations of this game are more conceptual than formal, but manner and meaning reinforce each other most when various pieces of music — usually classical piano pieces (by Mozart, Grieg, Bach, and Chopin) or African pop tunes — orchestrate the minimal action. On a couple of occasions, when musical seduction becomes the issue, either Kinsky or Bertolucci himself comes up with a form of attempted fusion. One of these is a rhythmic piano piece played by Kinsky as a kind of serenade to Shandurai; the other is one of McCoy Tyner’s ecstatic piano solos in John Coltrane’s first recording of “My Favorite Things.”

The latter piece is heard when Shandurai spies Kinsky half-asleep on a sofa, and the fact that we can’t be sure where this music is coming from — inside his head or hers, coming from an unseen radio or simply from the film itself, where the fluctuating consciousnesses of the two characters find some temporary and haphazard meeting ground — only intensifies the magic of the sequence. Besieged is the movie’s title, but “bemused” and “bewitched” better describe what these characters do to one another and what their subtle interplay often does to us. It can happen only in a movie, but what better place for it?