This is the first review I ever did for Monthly Film Bulletin, around the same time that I started working for the magazine (at the British Film Institute, then on 81 Dean Street) as assistant editor, in late summer 1974; this ran in their September issue. –J.R.

Amarcord

Italy/France, 1973 Director: Federico Fellini

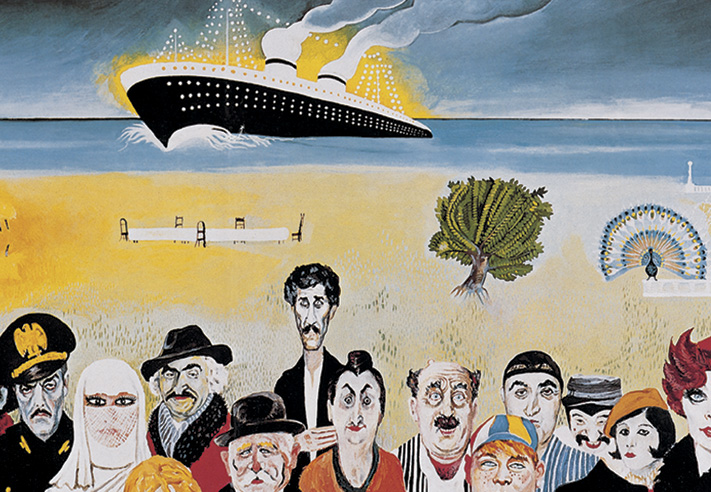

A small Italian town, during the Fascist period. The end of winter is announced by the arrival of manine, a white fluffy substance that blows into the province. That night, a large bonfire is built in the city square to celebrate the beginning of spring; a local resident recounts some of the town’s history. Volpina, the village whore, walks along the beach and flirts with construction workers, including Aurelio Biondi. At a stormy family dinner, Aurelio screams at his teenage son Titta for not working, and Titta is later sent b y his mother, Miranda, to the priest for confession. Asked whether he masturbates, he recalls and imagines several encounters with women in the town. A fascist rally is held to greet a visiting dignitary. That night, the police shoot down a gramophone from a church tower when they hear it playing a “subversive” song; prevented by Miranda from attending the rally, Aurelio is brutally interrogated by the police. Two episodes depict tall tales reputed to have taken place in the luxurious Grand Hotel: Grandisca, a glamorous local “star”, has a tryst with a visiting nobleman, and a pushcart dealer is invited into the suite of an Arabian harem. Titta’s family picks up his Uncle Teo at an insane asylum in the province; when they stop for lunch, Teo climbs a tree and shouts that he wants a woman , until a dwarf nun from the asylum coaxes him down. Most of the townsfolk go out to sea in boats to catch a glimpse of an enormous ocean liner, the Rex. Titta is invited by an abnormally large-breasted tobacconist to suck her nipples after he succeeds in lifting her huge body several times; he is next seen sick in bed. People leave the local cinema to watch the snow fall, and engage in snowball fights. Titta and Aurelio visit Miranda in the hospital. She dies, and a funeral is held. As manine returns to the town, Gradisca is seen at a festive outdoor wedding banquet; her bridegroom is a local and patriotic military policeman.

As the above summary suggests, Amarcord is virtually as plotless as all the Fellini films preceding it since Satyricon. The title means “I remember”, and although Fellini has discouraged a strict autobiographical reading of the film in interviews, fanciful memory is crucial to the overall texture. Designed perhaps as a companion piece to Roma –- a city film that was equally studio-shot -– this latest version of the Fellinian fresco can be distinguished from its predecessor by the broadness, simplicity, and calculated directness of its vulgarity, particularly in relation to its arsenal of sexual and scatological jokes: one feels that the director largely made it for as well as about the inhabitants of his hometown. While Roma had a tendency to linger over certain conceits (e.g., the ecumenical fashion show) long after their implications had registered, thereby underlining Fellini’s penchant for pure spectacle beyond narrative pretexts, most of Amarcord seems more carefully geared to the anecdotal appetites of a less demanding audience, delivering its comic punches like signal cards in a linear bead-like procession. Although the execution of his ideas is as energetic as ever, rarely has Fellini depended as much on shop-worn devices: his historical lecturer descends directly from the Stage Manager in Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, while his beach whore Volpina and gargantuan tobacconist comprise a collective replay of Saraghina in 8½.The cartoonist side of Fellini’s talent is expecially evident in these latter two figures, and despite their distinctly second-hand quality they do function as colorful details in the overall design. But they are “colorful” mainly as graphic elements rather than as characters, and indeed one of the many factors which decisively differentiates Amarcord from the Fellini of I Vitelloni is the reduction of neorealistic observation to a fairly exclusive repertoire of two-dimensional genre figures. Fellini remains a master of movement and animation, and one feels the presence of a director totally in control of his medium whenever he brings most of his actors together and juxtaposes their singular traits within the larger context of a community event. The notion of a three-ring circus that Fellini and many of his critics have frequently invoked in relation his work seems less operative, however, whenever he concentrates his camera on individual details and effects, and a comparison with Jacques Tati is particularly instructive (all the more so considering the director’s increasing use of isolated Tatiesque gags). The elaborate construction of paper cylinders by schoolboys to carry urine from the back of a classroom to the feet of an embarrassed student at the teacher’s desk is a gag that Fellini needs over half-a-dozen shots (one of them an extended track) in order to set up and articulate; when Tati delineated a somewhat similar gag in Playtime -– workmen in a café surreptitiously attaching metal tubes to sneak a free drink from a bottle behind the bar -– all he needed was a single shot and the spectator’s observation. In most of the gag sequences of Amarcord, Fellini apparently prefers spoon-feeding an audience to collaborating with them. The more luminous sequences of the film are, on the contrary, the ones where he can organize an interplay of elements around looser narrative structures, leading to a freer and less mechanical exposition: the town’s expedition by boat to look at the imposing edifice of the Rex (a sequence enhanced by beautifully back-lit sets which testifies to the glamorous lure projected by the Fascism of the period much more eloquently than the extended parade and rally); the uncharacteristically gentle episode involving Uncle Teo, which depicts the Biondis in all their diversity much more sympathetically than the hysterically over-directed family dinner; above all, the final sequence, dramatizing the bitter-sweet end-point of Gradisca’s dreams of romance and fame in a sprawling canvas of scattering details –- culminating, after the departure of the newly-weds, in a leisurely, almost lazy pan across the open landscape that takes in the few remaining stragglers. A substantial asset, of course, is the superbly evocative music of Nino Rota, who contributes to Amarcord one of his dreamiest scores to date -– a suite of short melodies including “Stormy Weather” (first heard offscreen, sung in Italian, during the family dinner, then reprised orchestrally in a subsequent sequence) along with memorable original material.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM

—Monthly Film Bulletin, September 1974, vol. 41, no. 488