From the Chicago Reader, November 22, 2007. Many thanks to Lance Booth for tracking down a contemporary response to this review that’s well worth reading (and heeding), regardless of whether it was Bob Dylan or someone else who wrote it. — J.R.

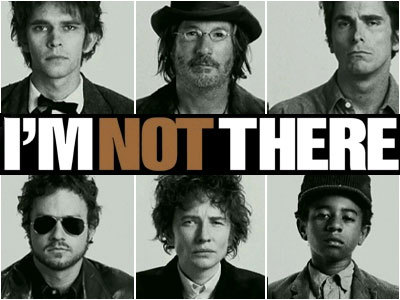

I’m Not There

Directed by Todd Haynes

I’ve owned copies of Don’t Look Back and Nashville Skyline for decades, but I’d never describe myself as a hard-core Bob Dylan fan. Obvious as his talent may be, he often mixes metaphors and combines images in a way that skirts the edge of incoherence. And as the appointed spokesman for my generation — born in 1941, only a couple of years before me — he sometimes strikes me as little more than a series of shifting masks and poses. So I went into I’m Not There, Todd Haynes’s ambitious new film about the man, fully prepared to feel out of step, and was surprised to find my misgivings addressed at every turn. Widely described as a tribute, it frequently comes across as a series of insults.

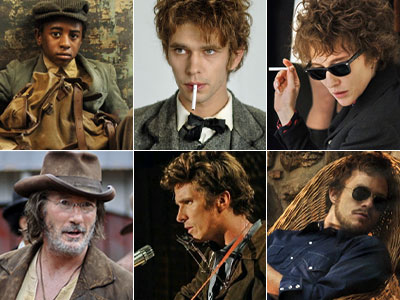

To call the film biographical is misleading. If anything, it’s a speculative essay that uses Dylan to comment on his audience and the 60s in general. Haynes, a graduate of the semiotics department at Brown University, isn’t really concerned with Dylan as an individual; rather he presents him as a cluster of signs and texts, spread across six characters embodying phases or distinct aspects of his early career. There’s an 11-year-old black boy (Marcus Carl Franklin) who calls himself Woody Guthrie; a white folksinger named Jack (Christian Bale) who reaches the mainstream via Greenwich Village and later becomes a born-again Christian; a poet (Ben Whishaw) who exists entirely inside an abstract space and identifies himself as Arthur Rimbaud; an actor named Robbie (Heath Ledger) who plays a fictional version of Jack in a movie; an electrified Dylan known as Jude (Cate Blanchett, giving the best imitation of the bunch) who conquers swinging London; and finally a Dylan who fancies himself Billy the Kid (Richard Gere). By the time the real Dylan appears in extreme close-up at the movie’s end, blowing on his harmonica, he simply registers as one more sign.

As semiology, I’m Not There is hardly impartial. It charts Dylan’s development from precocious kid (Franklin’s Woody Guthrie) to posturing asshole (Blanchett’s Jude) with increasing mockery. Nowhere are the criticisms more pointed than in the depictions of Jude and Robbie: both are blatant misogynists and the latter neglects his wife. Yet neither matches up with the Dylan we see in Don’t Look Back, D.A. Pennebaker’s documentary about his 1965 UK tour (a source Haynes plunders repeatedly). Especially compared to Jude, he’s far more impressive as both a musician and a human being. (On a similar note, Joan Baez comes across as much more subdued and prefeminist in Don’t Look Back than she does in Julianne Moore’s depiction of her, largely because the 60s were more prefeminist than Haynes would have you believe.)

Apart from Robbie’s wife, Claire — a dead weight at the center of the film in spite of Charlotte Gainsbourg’s charm and talent — nearly every supporting character in the film is a caricature. The fans who are livid about Dylan going electric are depicted as especially innocent and clueless. One of the few people assigned as much if not more credibility and insight as Dylan is a skeptical journalist modeled loosely on various reporters in Don’t Look Back. He confronts Jude for his apolitical self-absorption — an attack I find questionable, at least from a contemporary standpoint, as it ignores some of Dylan’s more recent work. Masked and Anonymous, the 2003 movie he pseudonymously cowrote and stars in, for example, is a blistering portrayal of the U.S. as a corrupt and greedy banana republic.

Haynes may raise issues with Dylan’s persona, but that doesn’t mean he isn’t working both sides of the street. Not only did he have Dylan’s permission to do the project, he employs so much esoteric Dylanology along the way that he’s clearly pitching to skeptics and specialists alike. A postmodernist who deals in pastiche, often appropriating the mystique of others, Haynes is guilty of some of the same double dealing as Dylan — a guy who comes on as a poet, man of the people, and political protester even as he disavows those identities entirely. Haynes is calling Dylan out for creating public confusion even while he does his part to keep that confusion going.

The moments when this semiological attack becomes hagiography aren’t always easy to spot. The first time I saw the film, I figured the fanciful “old west” town of Riddle, Missouri — where Billy the Kid and Pat Garrett both appear — was intended to show the confused and ahistorical way we tend to view westerns. Riddle is a jumble of freakish hippies and cowboys, where an ostrich, a giraffe, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, Franklin’s Woody Guthrie reconfigured as Charlie Chaplin, and a projected four-lane highway all come into play. When Billy the Kid and Woody Guthrie hop into the same boxcar, each carrying a guitar case labeled “This Machine Kills Fascists,” it seemed to suggest that both figures belong to the same mythological past. But when I later got the chance to ask Haynes about the Riddle segment, he traced many of its anomalies back to specific Dylan references, such as Greil Marcus’s metaphorical appreciation of The Basement Tapes — more evidence that how much I’m Not There plays as a critique or a celebration depends on what you bring to it. I’ve seen I’m Not There three times now, and apart from the politically correct sections with suffering Claire, I find it both nimble and gripping. But whenever I try to commit myself to any idea about what I think it’s doing, I ultimately balk at having too many choices. You might say I’m not there — at least not yet.