From the Chicago Reader (April 9, 1999). — J.R.

Western

Rating *** A must see

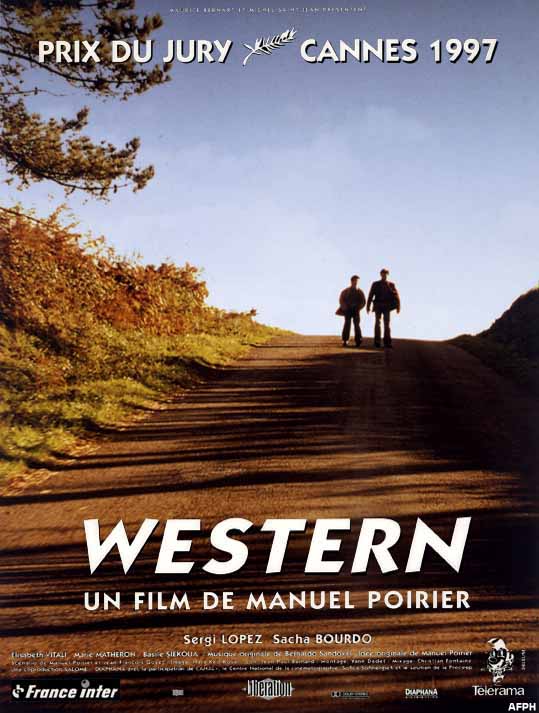

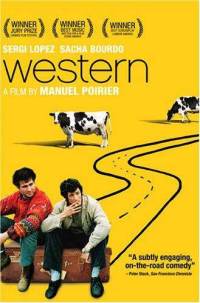

Directed and written by Manuel Poirier

With Sergi Lopez, Sacha Bourdo, Elisabeth Vitali, Marie Matheron, and Basile Sieouka.

The other day I received an E-mail from someone wanting to know how I could have described The Tree of Wooden Clogs as Marxist when it was so clearly a religious film. Actually Dave Kehr had written the capsule review of Ermanno Olmi’s feature 14 years ago, but I hastily E-mailed back that any Italian could tell you that Marxism can easily be seen as a form of religion. Afterward I realized that this response was flip. It would have been better to say that Catholicism and Marxism have had a long and complex coexistence in Italy, and that it was unrealistic to expect that they would be mutually exclusive as systems of belief; the career of Pier Paolo Pasolini is proof of how intimately the two can be intertwined, regardless of the contradictions involved. That led me to think about how the simple characterizations of European Marxism in this country foster such confusion. Shortly after this I happened to read Andre Bazin’s description of The Bicycle Thief as one of the great communist films — an aspect of the film I suspect couldn’t have been apparent to American audiences when it won the Oscar for best foreign film in 1949.

Given our extreme isolationism — in some ways perhaps even greater today than it was half a century ago — it’s logical that we tend to think of foreigners in stereotypical terms. After all, we have so little information and experience to draw on, and it’s symptomatic of the problem that we often think of non-Americans as wannabe Americans even though many of them clearly aren’t. So we wind up thinking about much of the rest of the world in shorthand; communists are nonreligious, the French worship Jerry Lewis, Iranian artists are heavily censored, the Chinese love fortune cookies. In fact, there are plenty of religious communists, Woody Allen is much more popular in France than Jerry Lewis, Iranians tend to revere artists more than we do, and Chinese fortune cookies are strictly for non-Chinese. But such data offer only fleeting clues about what we don’t know, and without more information they serve only as counterstereotypes — they hardly provide a comprehensive understanding of these cultures.

One of the most refreshing aspects of Manuel Poirier’s Western, a wonderful French comic road movie playing at the Music Box this week, is the way it explodes many common notions about France and French movies. For those who equate France mainly with Paris, here’s a movie set exclusively on Brittany’s coast and on only about a 25-mile stretch of it — Poirier has suggested that part of his idea was to make a road movie mostly without cars. Furthermore, the two central characters aren’t French in the way that term is typically understood, though they and the other characters speak French throughout.

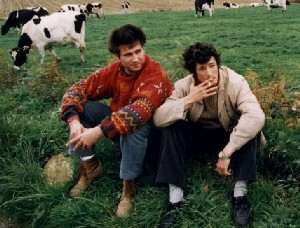

One is Paco (Sergi Lopez), who’s Catalan — not the same thing as Spanish, though he comes from Spain (confounding shorthand notions of who the Spanish are); the other is an itinerant Russian of Italian origins named Nino (Sacha Bourdo), who moved to France a couple of years earlier. Neither character is especially eccentric or exotic — we accept them both as regular guys from the outset — yet getting to know them takes most of the movie’s two-hour running time.

Paco is a shoe salesman only when the film opens. He picks up Nino as a hitchhiker, and shortly afterward Nino steals his car. Paco loses his job as a consequence, and when by chance he catches Nino on the street, he beats him up so badly that Nino has to spend a week in the hospital. Over a three-week period the two become road buddies, while Marinette (Elisabeth Vitali), a woman Paco met after his car was stolen, tries to decide whether to stay with him. Paco is seen as a skillful ladies’ man while Nino repeatedly strikes out with women, though this shorthand description is eventually undermined, as are some other assumptions about these people. Two of their more entertaining activities along the way are a fake public opinion poll about what constitutes the “ideal man,” concocted with the idea of finding Nino a girlfriend, and a game called “Good morning, France” that consists of greeting French pedestrians from cafe tables and scoring points on the basis of whether the greetings are returned.

We don’t discover that Paco is Catalan until 17 minutes into the film, and we have to wait about twice that long before we discover where Nino is from. Before then we’re apt to regard both characters as simply French — unless we can spot Catalan and Russian accents in French. I don’t want to suggest that having the information about Paco and Nino’s national origins completely transforms our sense of who they are, but it does alert us that we’ve been regarding France as homogeneous when it’s actually a melting pot. (Our understanding is similarly shifted in Abbas Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry when we learn that three of the four central characters aren’t Iranian even though they speak Persian.) One of the more memorable characters Paco and Nino meet in their travels, for instance, is a cheerful man from the Ivory Coast who identifies himself as Breton. (He’s the one who proposes the “Good morning, France” game.) Poirier — who has a Peruvian father and a French mother and has spent nearly all of his life in France — playfully highlights this diversity by appending national flags to each of the names in Western’s final credits.

Is this a political gesture or a poetic one? It depends. Asked “Do you feel your work is political?” in an interview in the French magazine Positif (recently translated in Projections 9), Poirier replied, “Definitely. All my films are political in their own way. I come from Peru myself. I cast two foreigners as my main characters, and the characters they meet come from all sorts of different places. This diversity was reflected in the crew. Mixing colors, flags was initially a poetic idea, not a political one, but now that we have the government’s campaign against illegal immigrants it does remind audiences what France is made of.” However, the film’s American press book states, “There is a strong dose of social optimism in Poirier’s story about love and friendship. Yet, unlike Guediguian’s Marius and Jeannette, for instance, whose Marxist political ideology is quite explicit, this film does not advance any particular ideology, and the director demurs from calling Western a political film. Rather, he uses a blend of irony, humor, and hope to deliver a message about integration and tolerance aimed squarely at the racism of France’s extreme right wing.”

This helps to clarify, for starters, that the word “political” doesn’t mean exactly the same thing in France and the U.S. It’s worth adding that the Western being described in the interview — the one that received the grand jury prize at Cannes in 1997 — is about 15 minutes longer than the U.S. release version. (It’s been a couple of years since I saw the original version, so I can’t detail the differences — though the original felt much longer, for better and for worse, and the U.S. version seems to end abruptly and in a less satisfying manner; I’m told, however, that Poirier reedited it himself.)

I haven’t seen any of Poirier’s three previous features (all of which, incidentally, feature Lopez as an actor), but colleagues familiar with some of them say they tend to ramble a bit — though they also say that’s an essential part of their charm and their overall generosity toward their characters. The dialogue in Western is mostly scripted, though it often seems improvised; there’s one double-date dinner sequence that recalls John Cassavetes, a master at giving an improvised feel to his own scripts. Yet this isn’t a chamber piece; Poirier shoots all his action in ‘Scope, thereby justifying his somewhat ironic title (which alludes in part to the action unfolding on the west coast of France) with a feeling of epic spectacle and opening up his comic adventures to a broad, picaresque world. As Poirier indicated in the Positif interview, he chose this format to honor his modest characters with something worthy of their own expansiveness.