From the Chicago Reader (May 18, 2001). — J.R.

The King Is Alive

*

Directed by Kristian Levring

Written by Levring and Anders Thomas Jensen

With Miles Anderson, Romane Bohringer, David Bradley, David Calder, Bruce Davison, Brion James, Peter Kubheka, Vusi Kunene, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Janet McTeer, Chris Walker, and Lia Williams.

The King Is Alive, directed and cowritten by Kristian Levring, is the fourth film to have the dubious honor of qualifying for certification under the rules of the Dogma 95 manifesto, whose professed aim is to get back to the basics of realism — shooting, for example, in natural locations with handheld cameras, direct sound, and natural lighting. But what’s basic or realistic and what isn’t, in terms of film history and technique? The manifesto also insists that movies be shot in color, a rather ahistorical reading of what’s basic — unless one labels all possible uses of color in film realistic and all possible uses of black and white artificial.

If that’s the operative assumption, The King Is Alive triumphantly refutes it. The movie was shot with three digital video cameras — unlike Thomas Vinterberg’s Dogma film The Celebration, which was shot with only one, and Lars von Trier’s Dancer in the Dark (not a Dogma film, but made by one of Dogma’s founders), which was shot with a hundred — and that might make it seem new as well as passé.

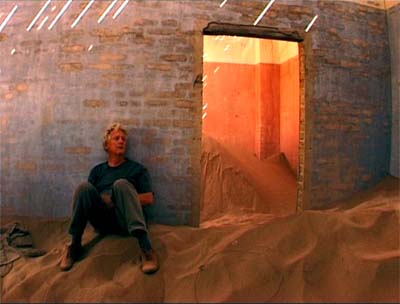

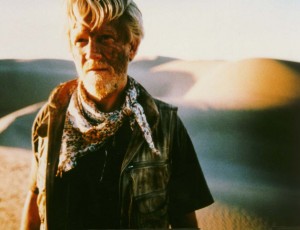

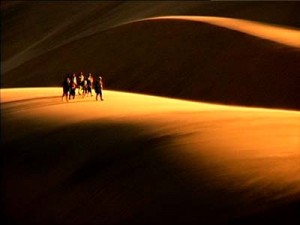

Certainly the look Levring, one of the original four cosigners of Dogma 95, gets from these cameras is fresh and at times even startling, featuring vivid, deeply saturated colors that practically glow in the dark; African desertscapes that seem sculptural (the film was shot in Namibia); and natural lighting effects that are often beautiful — at least according to conventional art-photography notions — such as sunlight streaming through windows and faces starkly silhouetted in close-ups.

I’m not entirely convinced that the cameras or settings are the only things responsible for this look. If Jean-Marc Lalanne — reviewing this film at last year’s Cannes festival for the newspaper Libération — is to be believed, most of the film’s “absolutely antinaturalist” color and lighting effects were achieved during postproduction, presumably through lab work, thereby breaking the first part of the fifth rule of Dogma 95, which decrees, “Optical work and filters are forbidden.” I don’t have enough technical knowledge to decide whether Lalanne is correct, but Levring definitely breaks the manifesto’s tenth rule — “The director must not be credited” — as, I believe, all the other filmmakers with Dogma 95 certificates have done. I think Levring has also broken the eighth rule — “Genre movies are not acceptable” — since The King Is Alive clearly belongs to a venerable subgenre in which Westerners traveling through the third world are brought together by chance, become stranded in the middle of nowhere, fight for survival, get on one another’s nerves, and show their worst sides.

Most examples of this subgenre involve plane wrecks, such as Sands of the Kalahari (1965) and Flight of the Phoenix (1966), two of the better entries that come to mind. Of course, given that both of these examples are from the 60s, what seems familiar or even shopworn to me might seem fresh or even innovative to someone younger — another example of how subjective any notion of “getting back to basics” can be.

Instead of a plane wreck, The King Is Alive has a bus full of tourists that runs out of gas in a small, deserted mining town in the African desert after steering off course because of a faulty compass. Otherwise the film differs from its genre predecessors mainly in its sexual candor, in its multifaceted unpleasantness — almost everyone in the group despises almost everyone else and goes out of his or her way to prove it — and in its odd decision to have the oldest member of the group, Henry (David Bradley), stage a production of King Lear while waiting for Jack (Miles Anderson), the most practical member of the group, to return with fuel for the bus.

Another spin on the formula is the inclusion of a wizened and hermitlike black sage, Kanana (Peter Kubheka), who sits around all day; he doesn’t speak a word of English, but as the offscreen narrator, he delivers a vague, poetic, and highly implausible commentary in his native tongue (subtitled in English) about the stranded people, all of whom, except the bus driver, are white. A sample of Kanana’s folk wisdom: “They ate a bit less every day. They said words the rest of the time.” The tourists’ only food, incidentally, is canned carrots — some of them dangerously spoiled — left behind by the miners. Kanana’s source of food, or whether he eats at all, is never revealed.

Henry’s decision to rehearse and stage King Lear is no more plausible, unless one translates the bored and unresourceful tourists into a troupe of bored actors — which is possibly what Levring had in mind. Taking his actors into the Namibian desert, he encouraged improvisations, some of which he used, and it appears that when he ran out of these he followed the lead of Henry in furnishing his cast with lines from King Lear. Some of these lines match the situations and the characters, but more often they don’t — an interesting device in itself, though its connection with the rest of the film is unclear.

Henry furnishes his companions with lines from the play by jotting down the ones he can remember on separate rolls of paper, then distributing them. How is it that he happens to remember most or all of the lines in Lear? The movie never gets around to explaining. In the press notes, Levring does say that his inspiration was an Englishman he knew who lived in the Mojave Desert and arranged evenings of Shakespeare with someone who worked in a nearby diner and someone else who worked at a filling station. Presumably it’s easier to substitute an African desert for one in the American southwest if you regard both as abstract or symbolic locations — fitting metaphysical backdrops for a figure like Kanana.

If I’d been interested in this movie’s acrimonious characters I might have appreciated the actors’ performances more. French actress Romane Bohringer seems mainly wasted playing a woman who’s Henry’s first choice for Cordelia, and Jennifer Jason Leigh acts up a storm playing an American bimbo who turns out to have more brains than expected; she winds up with the role. The other actors play characters who are too narrowly conceived to make for much interesting acting — Bruce Davison and Janet McTeer are cast as an American couple, Chris Walker and Lia Williams as an English couple, David Calder as a cynical Brit wrestling with a midlife crisis, the late Brion James (who played Leon, one of the replicants in Blade Runner) as an alcoholic businessman, and Vusi Kunene as the bus driver. Only the characters played by Kunene, Anderson, Bradley, and Kubheka are allowed to retain even a trace of dignity.

To be fair, Levring sets up some interestingly jagged editing patterns when he crosscuts toward the end of this movie, and the shots throughout are almost always visually striking. More generally, The King Is Alive justifies itself periodically as a set of experiments, a film more interested in seeking than in finding. But if this metaphysical stew is getting back to realistic basics — in terms of perceptions about human nature or aesthetics — I can only wonder what an artificial, decadent cinema must be like.