From the Chicago Reader (October 2, 1992). — J.R.

NORTH ON EVERS

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by James Benning.

A good many of the fine points of the film business elude me. But if I understand some of the current rules correctly, it’s poison to use black-and-white cinematography, letterboxing (for framing wide-screen formats on video), or subtitles –unless they appear in music videos or, in the case of subtitles, in Dances With Wolves or The Last of the Mohicans, when they automatically become commercially desirable.

I cite these ridiculous rules of thumb to show just how fanciful most such commercial “rules” turn out to be. Producers, distributors, and exhibitors often claim that their choices are dictated by the well-researched desires of audiences; of course audiences counter that they can only choose from what’s put in front of them. In other words everyone passes the buck when it comes to explaining why black-and-white features can’t get bankrolled in this country and why foreign-language films have a tough time — only 1 percent of all movies shown here are subtitled. And the industry takes enormous pains to ensure that we don’t see letterboxing on TV or video — except on MTV. I don’t know the exact figures, but wide-screen movies are routinely shorn of a third of their frames, then refilmed and recut in “pan-and-scan” versions for video use — and all to avoid letterboxing.

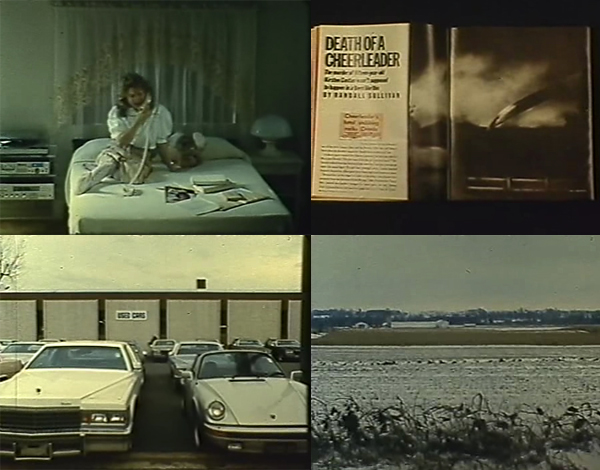

At least experimental films like James Benning’s North on Evers have one strong advantage — they aren’t even in the running when it comes to deliberations about financing. They’re true examples of free expression, unlike the Hollywood features that get thousands of times more attention. Practically all of this fascinating road movie by a master framer of landscapes, stretching from the west to the east coast and back again (showing at Chicago Filmmakers tonight with the filmmaker in attendance), is not only subtitled but subtitled in handwritten text that moves constantly across the bottom of the frame. Parts of the text are periodically rendered illegible by whatever’s in the lower portions of certain frames, and even when the text is legible it often detracts from what’s going on in the visuals. (In most foreign films reading subtitles might be compared to using bifocals, but reading them here, where they’re in constant motion, often means ignoring the images outright.) Moreover, though the procession of shots and the procession of text offer different versions of the same narrative — Benning’s cross-country trip by motorcycle, with many personal stops and one-night stands along the way — they’re rarely in sync or mutually enhancing: sometimes the text precedes the illustration by several minutes, and sometimes the pictures come well before the verbal description.

Benning overturns the notion of an easily consumable product at the outset of North on Evers, so if one of your basic requirements of picturegoing is being able to look fully at every frame, read all the subtitles, and synthesize both discourses into a single homogeneous narrative, watch out because with this movie you won’t even get to first base. Chances are, though, you’ll also miss the poignancy and poetry of Benning’s principles of overload and discontinuity.

An official movie-artist figure like Martin Scorsese or Woody Allen who proposed doing such a movie to a major studio would be thrown out on his ear; but a low-budget independent like Benning, once he gets his funding, can do whatever he wants, even if this happens to make more artistic than commercial sense. Part of what makes this film’s lack of a clear match between text and visuals so strong a statement is that it dramatizes the divided spirit, the fractured life, that’s the subtext of both the visual and verbal narratives.

Benning, born in Milwaukee and now living and teaching in southern California, is unquestionably one of our most talented American independents — he may even be the closest we’ve had to a poet laureate of the American midwest since the early features of Orson Welles, though Benning’s background is working-class rather than aristocratic. But two aspects of his work have rankled me in the past. First, unlike Welles he’s shown a tendency to regard all his filmmaking as necessarily apolitical. (He has said in interviews that he gave up political activism in the late 60s or early 70s for filmmaking, implying that the two are mutually exclusive.) Second, a certain false naivete seems to characterize many of the poses he adopts as an autobiographical artist — the sort of “aw shucks” demeanor we associate with American macho figures as diverse as Gary Cooper and Jack Kerouac. It doesn’t always sit convincingly with Benning’s obvious sophistication as a visual artist and his distinctly modernist approach to narrative and spectacle. Partly because of these problems, which I think are closely related as “all-American” stances, I’ve tended to prefer Benning’s less obviously autobiographical films — 11 X 14, One Way Boogie Woogie, Landscape Suicide [see below] — to those that flaunt personal references, such as Grand Opera: An Historical Romance, Him & Me, and Used Innocence. (I haven’t seen all his features, so this list is neccessarily incomplete.)

But in North on Evers Benning seems to be grappling with both his apoliticism and his falsely naive persona, attempting — not always successfully — to move beyond them. First, political concerns of the past and present are a central theme of the new film, and for once he doesn’t try to aestheticize these issues or isolate them from his other concerns or from each other. Second, his strategies for representing himself and his life seem more direct and less self-conscious than they’ve generally been in the past. His earlier autobiographical forays often smacked of calculation and a contradictory sense of both exhibitionism and concealment, but the written text here, though it certainly shows some degree of formal deliberation, seems fairly loose in what it reveals about his life and feelings–Benning seems to let the chips fall where they may rather than carefully prepare a self-portrait. (He carelessly misspells the name of actor Willem Dafoe — seen and identified earlier as a friend in New York — in the final credits.)

Eventually we discover that North on Evers is the result of careful planning as well as of spontaneous digression. While the subtitles constitute a fairly straightforward account of Benning’s cross-country travels, the shots behind the titles were filmed not on that trip but on another trip a year later whose apparent purpose was to document with 16-millimeter footage his previous journey. Although this fact is briefly explained in the subtitles, roughly two-thirds of the way through the film, this is one of the parts of the text that is obscured by the visuals. (Fortunately, I had a copy of the full written text to read after seeing the film.)

If we regard North on Evers as a sort of contrapuntal duet between two “texts,” both of which represent Benning’s initial cross-country trip, one of the more striking differences between them is that the shots appear to offer a chronological account of the trip while the subtitles, which begin at the same point, include flashbacks and flash-forwards. Among them is an especially detailed and dramatic account of picking up a Navajo woman the first night of his trip, which Benning recounts as a reflective and resonant anecdote to friends in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, fairly late in the film. Of course the trip itself, as Benning frequently reminds us in the subtitles, is motivated by past connections and associations, and what often emerges in the film is a kind of stocktaking that juxtaposes past and present, either personal or historical, as in the following examples:

“I stayed with an old friend in Albuquerque, New Mexico. We drank beer in his back yard. He told me a story about his daughter. I hadn’t seen him since 1974. His daughter was just three back then. She was eighteen now. We met in 1968 while trying to organize a poor White ghetto in Springfield, Missouri. Later we painted houses in Milwaukee. . . .

“I stayed with two young women in Dallas. They worked as waitresses. I arrived on Juneteenth Day. In the afternoon we listened to gospel music, and at night I went to an all Black rodeo. I had never heard of Juneteenth Day. Slaves in Texas were freed months late. Juneteenth commemorates that day.”

What we see in the shots are mainly landscapes and formally posed portraits of friends and relatives; what we hear is mainly ambient sound — insects, birds, rain or wind — rather than speech, although there’s a snatch of dialogue from Sweet Smell of Success (presumably on TV, while we look at cows grazing), along with a few words spoken to the camera by a child and a canned lecture on Mount Rushmore. Some of the historically resonant spots on Benning’s itinerary include the Trinity site, New Mexico, “the birthplace of the Atomic Age”; Austin, Texas, where the mass murders of Charles Whitman occurred; Eureka Springs, Arkansas, stronghold of Gerald L.K. Smith and “White, Christian America”; Graceland in Memphis, with its fascinating array of graffiti; Jackson, Mississippi, where NAACP field secretary Medgar Evers was shot in 1963; Hank Williams’s grave; the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C.; a Klan booth in Sturgis, South Dakota, selling posters celebrating the assassination of Martin Luther King (“Our Dream Came True”); Robert Smithson’s ecological sculpture in Utah, the Spiral Jetty, now submerged under two feet of water; and Hoover Dam, on the Colorado River between Nevada and Arizona, “a WPA project built during the Great Depression. In 1932 it symbolized hope for the future, but now I saw it as one of the last technologies to be trusted. It shined brightly in the afternoon sun.” The list of personal stops is perhaps even longer: it includes friends, former lovers, acquaintances, various folk artists doing their work, and Benning’s 85-year-old mother and 17-year-old daughter, Sadie (a highly gifted video artist).

What finally emerges is an extremely evocative picture of what’s happened and is happening in this country from someone who would clearly like to feel patriotic today but finds patriotism very difficult. (Appropriately, we hear Jimi Hendrix’s “Star Spangled Banner” over the final credits.) I would venture that the sense of political impotence in Benning’s filmmaking is directly connected to the sense of overload: he forces us to take in both the shots and the subtitles, the past and the present, the sounds and the images. This is a country defined by such overstimulation and excess, and one of the best things about Benning’s narrative scrapbook is that it never allows us to imagine that either one of the texts, or even both of them together, is sufficient to encompass his subject’s complexity. (By contrast, the excess of most Hollywood features serves merely to paper over a void, or at least a dearth of material.)

Piling on layer after layer seems only natural to an alienated artist seeking to organize a surfeit of memories and experiences so that they speak with a single voice. To make this film Benning had to make the same trip twice. To watch it even once is to be distracted, but in an evocative and resonant manner — to be drawn away from Benning’s travels and alienations and reminded of one’s own.