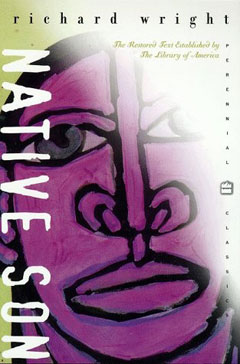

Political incorrectness has a lot to do with what still gives this novel much of its shocking power: the fact that Richard Wright refuses to make Bigger Thomas sympathetic or his crimes in any way excusable, even though he understands perfectly and very cogently how and why this character can murder as readily as he does— not only a white philanthropist’s daughter, whom he accidentally smothers, but also Bigger’s own girlfriend, whom he kills with a brick quite deliberately, almost immediately after they have sex. Recently reading this 1940 Chicago novel for the second time, I was reminded of both Dostoevsky and Camus (even though, novelistically speaking, Wright is miles ahead of L’Étranger). There’s something schizophrenic as well as dialectical about the way Wright can grasp the thought processes of his primitive young hero and then can offer a lengthy intellectual discourse about those processes. Eventually the communist discourse and arguments in the book’s second half drown out Bigger’s identity, but the way Bigger himself is allowed to dominate the discourse in the first half is the book’s unambiguous and terrifying triumph.

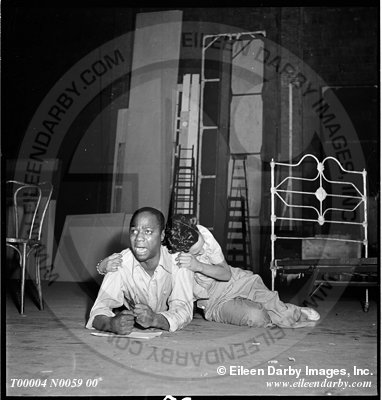

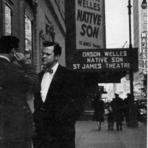

I wonder how the Welles stage adaptation handled this duality–especially with the plot handled in flashback, from the vantage point of the trial, and without an intermission. (See the two photos below with Canada Lee; I believe he’s standing with Ray Collins, who played Bigger’s defense lawyer, in the first.) This was Welles’s first major creative work after Citizen Kane, put together over seven weeks while waiting for that film to be released; it was his last successful stage production, and Simon Callow notes that it was on Broadway during the same season as Arsenic and Old Lace, Lady in the Dark, Johnny Belinda, Pal Joey, The Corn is Green, and The Man Who Came to Dinner.) John Houseman in his autobiographical Run-through offers us a detailed account of how he and Wright brought the play back to the terms of the novel after Paul Green’s inflections led it astray, but apart from this and Callow’s even more detailed account of the production in Orson Welles: The Road to Xanadu, we don’t have very much in print about it. [2/10/09]