These liner notes were written for Home Vision Entertainment circa 1997. —J.R.

Drôle de drame

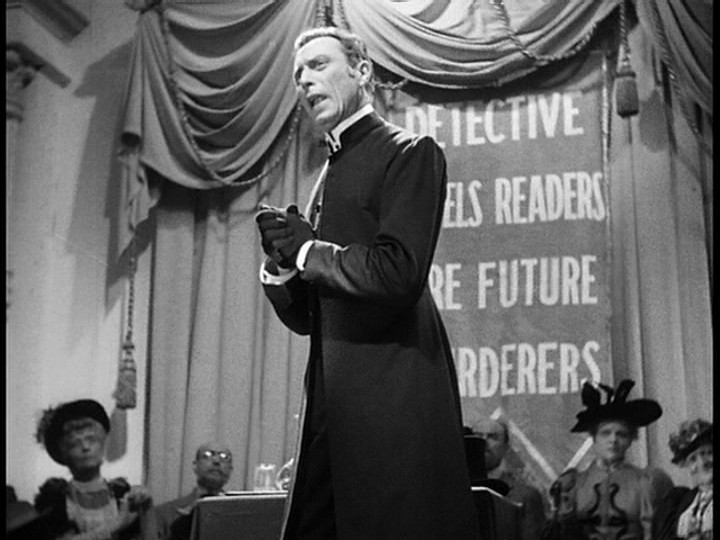

The English release title of Drôle de drame (1937) —- set in London circa 1900, and based on J. Storer Cloutson’s English novel His First Offense — is Bizarre Bizarre. This curious label derives from a conversation between Irwin Molyneux (Michel Simon) — a horticulturist who’s been writing crime novels on the sly, under the pen name of Félix Chapel, at the insistence of his wife Margaret (Françoise Rosay), to raise money to keep up their social appearances —- and Archibald Soper, the Bishop of Bedford (Louis Jouvet), Margaret’s hypocritically prudish cousin, who’s been publicly denouncing Chapel’s novels, and has just invited himself over for dinner due to his partiality for Margaret’s orange duck.

Unfortunately, Margaret’s cook and butler have just quit, leaving Margaret in a state of a panic—-because her servants are as necessary to her public image as the money brought in by Irwin’s moonlighting. So she prepares the duck herself while hiding in the kitchen, gets Irwin’s assistant Eva (Nadine Vogel) to serve it, and asks Irwin to come up with a story explaining Margaret’s absence.

In response to the Bishop’s prying questions, Irwin impulsively comes up with two explanations — that Margaret left for the country to visit friends and that she had to leave suddenly due to the measles —- and then tries to reconcile them by adding that it’s her friends who have the measles. The following dialogue ensues:

SOPER: Where do your friends who have the measles live?

MOLYNEUX (fumbling): Where do they live, precisely? Dear cousin, are you asking me for their precise address? …It’s very simple. They live precisely in the Brighton area, I believe.

SOPER (suspiciously): You believe so, dear cousin? (He looks at his knife.) Bizarre, bizarre.

MOLYNEUX: What’s the matter?

SOPER: With what?

MOLYNEUX: Your knife.

SOPER: In what way?

MOLYNEUX: You looked at your knife and said, “Bizarre, bizarre,” so I thought—-

SOPER: I said, “Bizarre, bizarre”? How strange! Why would I have said, “Bizarre, bizarre”?

MOLYNEUX: I assure you, dear cousin, you said, “Bizarre, bizarre—”

SOPER: I said, “Bizarre”? How bizarre!

It’s a characteristic moment of farcical complication breeding more farcical complication, which spreads like a giddy fungus throughout the movie. Critic Donald Phelps has aptly noted that “The [film’s] theme — a number of status-bound Britishers are raped by their imaginations, or common imagination -— is fulfilled by [Jacques] Prévert and [Marcel] Carné’s ingenious way of interlocking two genres: British melodrama and French domestic comedy-of-intrigue.” (1) What makes Soper’s musing doubly appropriate is that the results of this interlock are pretty bizarre — even if all the ingredients are immediately recognizable.

It was surely thanks to this bizarreness that Drôle de drame — in spite of its wonderful performances from a high-profile cast — was, according to French film scholar Dudley Andrew, “the only failure, commercial or critical, that its director Marcel Carné experienced among his first seven features” (2). Like François Truffaut’s Shoot the Piano Player — another genre mix that initially flopped with the public — Carné’s own second feature mutated into a treasured classic once audiences could see past its weirdness to discover how funny much of it was.

By then, Carne’s first seven features comprised an imposing lineup that also included, in addition to Jenny (his first feature, 1936), Quai des brumes (Port of Shadows, 1938), Hôtel du Nord (1938), Le jour se lève (1939), Les visiteurs du soir (1942), and Children of Paradise (1945). Prévert worked on the scripts of all these except for Hôtel du Nord, set designer Alexandre Trauner worked on all except for Jenny, and many other participants in Drôle de drame would work with Carné and Prévert again, including cinematographer Eugen Schüfftan and actors Jouvet and Jean-Louis Barrault.

In fact, Barrault’s Chaplinesque exuberance as a mime in Children of Paradise is already evident in his giddy embodiment of William Kramps — a mad serial killer specializing in butchers who’s also on the prowl for Chapel, which doesn’t prevent him from also befriending Molyneux and wooing Margaret at the same time. (Innocent lunatics with artistic temperaments are a Prévert specialty.) And if some of the wildness here also evokes the surreal abandon of the Marx Brothers — with relatively straightforward romantic episodes between Jean-Pierre Aumont (as a milkman) and Vogel providing the only anchor to normality — it’s worth adding that, apart from Kramps and this couple, the stuffed shirts and the maniacs in the plot usually turn out to be the same people.

Drôle de drame’s capacity to find the bizarre within the familiar is already present in the opening shot. As the late Jill Forbes noted, “The charm of Trauner’s sets is the charm of recognition, the pleasure deriving from the fact that the physical environment is exactly as the viewer somehow always expected it to be, a second-level recreation based on the impressions of other artists and illustrators already in wide circulation.” (3) So when the camera swoops down on a cozy, artificial, and utterly stagebound universe —- a bustling London street we immediately know, made strange only by the French view of the English enclosing it —- we already find ourselves, like the characters, mired in delightful duplicity.

———————————————————————————

Notes

1. “Droll Drama,” Moviegoer no. 2, Summer/Autumn 1964, p. 61.

2. Mists of Regret: Culture and Sensibility in Classic French Film, Princeton University Press, 1885, p. 83.

3. Les Enfants du Paradis, British Film Institute/University of California Press, 1997, p. 21.