Written for Artforum (February 2015). — J.R.

Doomed by shifting postwar social and political agendas, the never-completed documentary German Concentration Camps Factual Survey — launched in April 1945 by the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force and shelved in September — might have been the key nonfiction film on the subject had it been finished and shown as originally planned, as required viewing for German prisoners of war. Shot by trained GI cameramen accompanying British, American, and Russian troops as they liberated the camps, it might even have served as the principal disclosure to the rest of the world of the hitherto unthinkable conditions these troops uncovered.

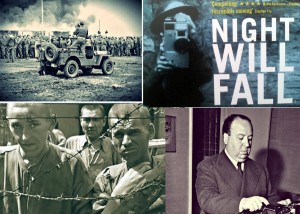

Produced by Sidney Bernstein — an old chum of Alfred Hitchcock’s who would later produce, uncredited, Hitchcock’s Rope (1948), Under Capricorn (1949), and I Confess (1953), and who persuaded Hitchcock to come to London to supervise the documentary’s postproduction — the film was halted by British embarrassment about the tangled fate of camp survivors (many of whom chose to remain in the camps, having nowhere else to go), combined with a reluctance to further demoralize the postwar German populace. But there was still enough of a desire to educate (or browbeat) the Germans to engage Billy Wilder to make a short film using parts of the atrocity footage, yielding Death Mills, which premiered in 1945 to five hundred viewers in Würzburg after a Lilian Harvey operetta, although only seventy-five or so remained to the end. Later, Bernstein’s documentary material became more consequential, put to use as evidence in the war crimes trials in Nuremberg and elsewhere.

London’s Imperial War Museum — which in 1952 acquired a silent rough-cut of five of the projected six reels of Bernstein’s film, along with a hundred reels of unedited footage and detailed script materials (including a text for a voiceover commentary and a complete shot list for the completed film) — showed this incomplete version at the Berlin International Film Festival and on PBS in the mid-’80s. In 2008, it managed to locate virtually all the materials needed for the sixth reel and began a full “restoration” of the film as originally conceived, which premiered a year ago, again at the Berlin film festival, and will come to the US later this year.

André Singer’s Night Will Fall — a fascinating HBO doc which premiered on January 26 — isn’t that film but, rather, an account of the project’s history, including excerpts from the latest IWM version. As such, it suffers similarly from a displacement and scrambling of agendas in which packaging is as much of a hindrance as presentation. For starters, no mention is made of either of the Berlin festival premieres or the specific work carried out by the IWM. The contemporary recording (by Jasper Britton) of the original scripted voiceover, combined with a sound track that combines sync-sound recordings made at Bergen-Belsen in 1945 with other sounds taken from battlefields in northwestern Europe in 1944 and 1945, necessarily makes this a postmodern re-creation, not a restoration. And things are muddled further in Night Will Fall’s framing narration, provided by Helena Bonham Carter, which informs us early on that “This film . . . has been described as a forgotten masterpiece of British documentary cinema, yet it was abandoned, unfinished, until now, seventy years later.”

The ambiguity as to what’s actually meant by “masterpiece” as well as by “now” only exacerbates the viewer’s various confusions. I’m reminded of Turner Classic Movies’ 1999 ad copy for the premiere of a 239-minute version of Erich von Stroheim’s Greed, lengthened by ninety-nine minutes of added intertitles and doctored production stills: “In 1924, Erich von Stroheim created a cinematic masterpiece that few would see — until now.” But given the merchandizing and consumerist frenzy attendant to all things collectible, which has even led to some of Orson Welles’s unfinished films being canonized in “definitive” editions (e.g., the Criterion Collection’s Complete Mr. Arkadin), it’s unsurprising that the IWM’s (presumably) more historically informed completion would be represented this way, even though we can’t yet see it.

Fortunately, much of the remainder of Night Will Fall works against this unearned rhetoric. Bolstered by recent interviews with surviving concentration camp inmates, soldiers, camera crew members, and two IWM curators, as well as by archival interviews from the 1940s (including Wilder, speaking in German about Death Mills) and ’80s), the grisly, harrowing footage of corpses in Belsen, Buchenwald, and Dachau quickly and decisively overwhelms any auteurist interest in Hitchcock’s contribution, which is briefly chronicled about fifty minutes into the eighty-minute film. (We learn that his chief concerns were, first, to make the atrocity footage “convincing” by favoring long takes, and, second, to emphasize the proximity of the camps to ordinary German life through the use of map inserts.)

It’s interesting to see the British troops forcing local Germans to tour the camps and ordering SS officers and soldiers to dispose of the corpses, although similar revelations are found in Emil Weiss’s Falkenau, the Impossible: Samuel Fuller Bears Witness (1988), where Fuller comments on his own silent amateur footage (the first film he ever shot) recorded at a Czech death camp. And it’s striking that Hitchcock shared with the Soviet camera crews a prescient worry that, confronted with such unspeakable horrors, the general public might suspect that the atrocity footage could have been staged.