From the Chicago Reader (May 1, 2000). — J.R.

A gorgeous mirage of a movie, Claire Denis’ reverie about the French foreign legion in eastern Africa (1999, 90 min.), suggested by Herman Melville’s Billy Budd, Foretopman, benefits especially from having been choreographed (by Bernardo Montet, who also plays one of the legionnaires). Combined with Denis’ superb eye for settings, Agnes Godard’s cinematography, and the director’s decision to treat major and minor elements as equally important, this turns some of the military maneuvers and exercises into thrilling pieces of filmmaking that surpass even Full Metal Jacket and converts some sequences in a disco into vibrant punctuations. The story, which drifts by in memory fragments, is told from the perspective of a solitary former sergeant (Denis Lavant, star of The Lovers on the Bridge) now living in Marseilles and recalling his hatred for a popular recruit (Gregoire Colin) that led to the sergeant’s discharge; the fact that his superior is named after the hero of Jean-Luc Godard’s Le petit soldat and played by the same actor almost 40 years later (Michel Subor) adds a suggestive thread, as do the passages from Benjamin Britten’s opera Billy Budd. Most of all, Denis, who spent part of her childhood in Djibouti, captures the poetry and atmosphereand, more subtly, the women of Africa like few filmmakers before her. Read more

Narita: Heta Village

From 1967 to 1974 Japanese documentarian Shinsuke Ogawa lived with the farmers of Sanrizuka, whose village was targeted for demolition to make room for Tokyo’s Narita airport. Supported by radical students, the farmers protested their eviction, and Ogawa joined in, recording both the long-term struggle and the everyday life of the village. His intense involvement eventually yielded five films with a combined running time of about 15 hours; the 146-minute Narita: Heta Village (1973) is the second and final segment included in Doc Films’ retrospective of virtuoso cinematographer Masaki Tamura. Ogawa emphasizes the lifestyle and traditions the farmers are fighting to preserve, and both he and Tamura (a farmer’s grandson himself) show a deep sensitivity and responsiveness to these people. My favorite sequences include an interview with a woman while she slices a radish into the shape of a phallus (which she jokingly attaches to sweet potato “testicles”), a candid and affectionate conversation with an 86-year-old woman seated on her porch, and an opening sequence in which Tamura’s camera roams around a field to illustrate a farmer’s anecdotes. Subjective and highly empathetic, this documentary is less a statement than a friendly conversation: Ogawa can be heard frequently as both narrator and interviewer, the periodic intertitles are no less personal, and the villagers repay the filmmakers’ warmth by freely sharing their lives with the camera. Read more

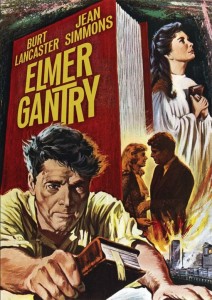

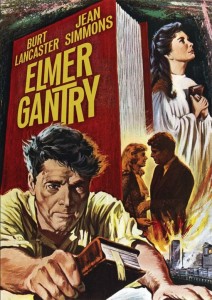

From the October 1, 1999 Chicago Reader. A personal note: This was the first film I ever saw in Chicago, when I was 17. I saw it at the Chicago Theater in between two train rides — the first from Sheffield, Alabama to Chicago, the second from Chicago to a Jewish camp in Wisconsin. — J.R.

Burt Lancaster on the Bible-thumping circuit, in Richard Brooks’s juicy (and considerably watered-down) 1960 adaptation of the Sinclair Lewis novel. Brooks was the ultimate vulgarizer of serious literature, as his versions of The Brothers Karamazov and Lord Jim made clear; this is somewhat better only because of Lancaster’s energetic performance, which won him an Oscar, and a few bits of colorful period ambience. Other Oscars went to supporting actress Shirley Jones and to Brooks for his highly dubious script. With Jean Simmons and Dean Jagger. (JR)

Read more