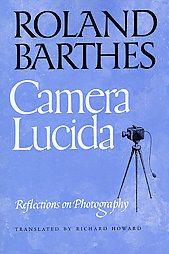

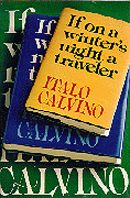

This is one of the last book reviews that I wrote for The Soho News, a weekly alternative newspaper in New York that didn’t survive the 1980s but that afforded me during the early part of that decade my only extended and regular opportunity to date to review books as well as films. This particular piece, a double review, ran in their August 18, 1981 issue, under a different title (“Reading about looking”), and I was pleased to hear some time later from Susan Sontag that it was of my pieces that she clipped. –J.R.

Reading about Looking and Looking at Reading

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography

By Roland Barthes

Translated by Richard Howard

Hill and Wang, $10.95.

If on a winter’s night a traveler

By Italo Calvino

Translated by William Weaver

Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, $12.95

In most bookstores, the new Barthes and Calvino books stare at one another like mutually envious friends in their separate ghettos, eyeing one another across a great divide and empty space: the social space separating essay from fiction.

Barthes’ grief-stricken gaze at photography sees beyond it to his own desire, then sees beyond that desire to the hypothetical Proustian (or Jamesian) novel he will never write — a nervous gaze that leaps like a butterfly across a crowded garden, never lingering with any simple petal-like photo for long, frustrated and impatient at the uselessness of this activity in summoning back his beloved mother. Read more

This review appeared in the March 1975 issue of Monthly Film Bulletin. —J.R.

Saikaku Ichidai Onna (The Life of Oharu)

Japan, 1952 Director: Kenji Mizoguchi

According to scriptwriter Yoda Yoshikata, Mizoguchi’s ambitions for The Life of Oharu were largely stimulated by the prize accorded to Kurosawa, a relative newcomer, for Rashomon at Venice in 1951. The bet paid off, and Oharu was awarded the Silver Lion at Venice in 1952, thereby inaugurating Mizoguchi’s international reputation at the age of fifty-six, four years before his death. Differing substantially from Saikaku’s novel –- a looser collection of episodes narrated by an elderly nun recalling her decline from a promising youth, and ending with a scene of a prostitute entering a temple and hallucinating the faces of former lovers in the idols there -– Oharu’s script gravitates round the feudal persecutions of one woman. It appears that Mizoguchi was something of a Stroheim on the set -– requiring that the garden of Kyoto’s Koetsu temple be “rebuilt” instead of using the nearly identical original location, and firing his assistant, Uchikawa Seichiro, when the latter complained about making last-minute changes in the positions of the studio-built houses for the scene of Bunkichi’s arrest. Read more

From the Chicago Reader, September 4, 1987. — J.R.

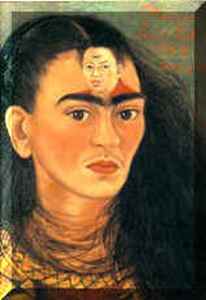

FRIDA

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Paul Leduc

Written by Leduc and Jose Joaquin Blanco

With Ofelia Medina, Juan Jose Gurrola, Salvador Sanchez, and Max Kerlow.

WOLF AT THE DOOR

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Henning Carlsen

Written by Carlsen, Christopher Hampton, and Jean-Claude Carrière

With Donald Sutherland, Max von Sydow, Valerie Morea, Sofie Graboel, Fanny Bastien, and Merete Voldstedlund.

We live in an increasingly visual culture, but there are signs that we haven’t quite got the hang of it yet. We still confuse image with event and one medium’s capabilities and limitations with another’s, falling into the trap of assuming that everything is seeable, hence realizable on a TV or movie screen. We still let our (not all that) new toys decide for us what it is we’ll say and how it is we’ll say it. Don’t believe the Sunday supplements: we won’t truly have entered the age of visual literacy until we can turn on the television in the evening and see not one single image of a politician waving from the doorway of an airliner.

When that day comes, we’ll probably discover that the film biographies of painters have vanished as well. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (December 16, 1988). — J.R.

MISSISSIPPI BURNING

no stars (Worthless)

Directed by Alan Parker

Written by Chris Gerolmo

With Gene Hackman, Willem Dafoe, Frances McDormand, Brad Dourif, R. Lee Ermey, and Gailard Sartain.

This whole country is full of lies. — Nina Simone, “Mississippi Goddam”

The time in my youth when I was most physically afraid was a period of six weeks, during the summer of 1961, when I was 18. I was attending an interracial, coed camp at Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee — the place where the Montgomery bus boycott, the proper beginning of the civil rights movement, was planned by Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks in the mid-50s. As a white native of Alabama, I had never before experienced the everyday dangers faced by southern blacks, much less those faced by activists who participated in Freedom Rides and similar demonstrations. But that summer, my coed camp was beset by people armed with rocks and guns.

I believe that we were the first group of people who ever sang an old hymn called “We Shall Overcome” as a civil rights anthem, thanks to the efforts of the camp’s musical director, Guy Carawan. Read more

This review from the August 1975 Monthly Film Bulletin (vol. 42, no. 499) probably features my first use of the word “diegesis“, which I must have learned about very shortly before. (As I recall, it was Laura Mulvey who explained to me what the term meant.) I’m not at all confident now that I absolutely had to use it.

An email sent on 9/4/09 from Adrian Martin: “Great to re-read your MFB pieces, which were among the earliest writings of yours I encountered as they appeared ! But your memorable NUMBER 17 piece raises a great historic mystery that has often plagued me, and which (I now realise) you may be at the centre of !! And that is the mysterious (mis)spelling of ‘diegesis’ – that is definitely the correct spelling, via the Greek root – as ‘diagesis’, which (as I recall) ran rife through FILM COMMENT and SIGHT AND SOUND for a while in the mid to late 70s (after a while, it seemed like some editorial superimposition by Corliss or Houston or whomever). It seemed to me, at the time, as the biggest symptom of the non- communication between film journalism and the theory academy! But maybe you have another version of where ‘diagesis’ came from ?? Read more

This appeared in the July 1976 issue of Monthly Film Bulletin (vol. 43, no. 510). 8/25 correction/ postscript: Ehsan Khoshbakht, who provided me with some more illustrations, informs me that (a) Sedric is playing tenor sax, not alto, (b) that a fourth Waller soundie that wasn’t included in the compilation I reviewed, “Your Feet’s Too Big ,” was actually the first one, and that (c) the photo at the bottom of this post, which I included just because I like it, actually comes from Stormy Weather. —J.R.

Fats Waller

U.S.A., 1941

Director: Warren Murray

Dist—TCB. p.c—Official Films. m/songs–“Ain’t Misbehavin'”, “Honeysuckle Rose”, “The Joint is Jumpin'” by Thomas “Fats” Waller. performed by–Fats Waller (piano, vocals), John Hamilton (trumpet), Gene Sedric (alto sax), Al Casey (guitar), Cedric Wallace (bass), Wilmore “Slick” Jones (drums), Myra Johnson (vocals). No further credits available. 314 ft. 9 min. (16 mm.).

A collection of three “soundies” made in the early Forties — mini-films designed to be shown on tiny screens inside jukeboxes — this entertaining short displays Waller’s showmanship at its flashiest. Read more

I’m waiting for any of the enthusiasts for Inglourious Basterds to come up with some guidance about what grown-up things this movie has to say to us about World War 2 or the Holocaust — or maybe just what it has to say about other movies with the same subject matter. Or, if they think that what Tarantino is saying is adolescent but still deserving of our respect and attention, what that teenage intelligence consists of. Or implies. Or inspires. Or contributes to our culture.

For me, assuming that it’s a message worth heeding or even an experience worth having is a little bit like assuming that Lars von Trier is closer to Sergei Eisenstein than to P.T. Barnum, as many of my colleagues also seem to believe — a genuine film theorist and not just a consummate con-artist who knows how to work the press.

I’ll concede that when Tarantino recently (and plausibly) faulted Truffaut’s The Last Metro as a film about the French Occupation that should have been a comedy, that qualified, at least for me, as a grown-up observation, and one that made sense to me. I just don’t see any comparable observations in his movie.

Part of the assumption of his defenders seems to be that no subject is so sacrosanct that it can’t be met with an adolescent snicker — including, say, the Holocaust or, closer to the present, 9/11. Read more

This appeared in the December 8, 1989 issue of the Chicago Reader. –J.R.

THE FILMS OF WILLIAM KLEIN

At a time when the National Endowment for the Arts is under siege — and not only from yahoos like Jesse Helms, but also from certain anarchists, leftists, and intellectuals — the general paucity of information and understanding about national funding of the arts in other countries only helps to underline how isolationist this country has become in cultural matters. As a rule, our overseas news coverage and our access to foreign films both seem to operate according to the same chillingly reductive circular reasoning: if people don’t already know about something or understand it, they aren’t likely to be interested.

Thus reports last spring of the demonstrations in Tiananmen Square routinely assumed that any popular sentiments in China that didn’t support the status quo automatically had to be “pro-democracy”; a lifetime of U.S. reporting has been devoted to the principle that only two political positions exist in the world, not three or six or 30 or 600. By the same token, most of the foreign films that we wind up seeing are those that support rather than challenge our generally clichéd notions of what other countries are like. Read more

Apart from Woody Allen, “the American filmmakers” discussed in this review — which appeared in the March 1976 issue of Monthly Film Bulletin (vol. 43, no. 506) — were apparently Frank Buxton, Len Maxwell, Louise Lasser, Mickey Rose, Julie Bennett, and Bryna Wilson, all credited jointly with Allen for the “script and dubbing” of the 1964 Japanese feature Kizino Kizi that was originally written by Hideo Ando. In recent years, Allen has routinely omitted this film from his filmography, but I persist in finding it one of his funniest. — J.R.

What’s Up, Tiger Lily? [Kizino Kizi]

U.S.A, 1966

[Director: Senkichi Taniguchi]

The wonderful surprise of What’s Up, Tiger Lily? — a modest exploitation exercise which predates Woody Allen’s career as a director, and has inexplicably taken a full decade to reach England — is how much mileage it gets out of what might seem to be a very limited conceit; for sheer laughs alone, it is arguably the most consistently funny film in which Allen has so far taken a hand. Undoubtedly a crucial factor in its success derives from the cheerful fashion in which the American filmmakers foreground their principal strategies. Unlike the dubious practice of an American TV cartoon series which slyly perpetuated the racist stereotypes of Amos ‘n’ Andy by assigning similar voices to animal characters, this 1966 jeu d’esprit avoids the chauvinistic possibilities inherent in a reverse procedure post-dubbing live-action Japanese actors with American voices, many of them evocative of cartoon animals — by beginning with material that is already reeking with American influence, and by taking care to remind audiences of what is being done every step of the way. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 26, 1996). — J.R.

David O. Russell, the writer-director of Spanking the Monkey, offers another naughty comedy — this one less independent and much more farcical (1996), with more familiar names in the cast. A young east-coaster (Ben Stiller) with a wife (Patricia Arquette) and baby son is contacted by a psychologist (Tea Leoni) who wants to reunite him with his biological parents — whom he hasn’t seen since infancy — and videotape the results for her research. After attempting to placate his adoptive parents (George Segal and Mary Tyler Moore), he and his family and the psychologist all take off cross-country. The results are watchable enough — sometimes funny, sometimes over the top — and fairly fresh, though also a bit calculated. Leoni has an interesting comic presence one would like to see in toothier material, though this certainly has a few bites. With Alan Alda, Lily Tomlin, and Richard Jenkins. R, 92 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (December 20, 2002). — J.R.

Gangs of New York

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Martin Scorsese

Written by Jay Cocks, Steven Zaillian, and Kenneth Lonergan

With Leonardo DiCaprio, Daniel Day-Lewis, Cameron Diaz, Liam Neeson, Jim Broadbent, John C. Reilly, Henry Thomas, Brendan Gleeson, and David Hemmings.

For almost the first two-thirds of Martin Scorsese’s 168-minute Gangs of New York, I was entranced. I felt like I was watching a boys’ bloodthirsty adventure story — a blend of pirate saga, 19th-century revenge tale (three parts Dumas to one part Hugo), sword-and-sandal romp, and Viking epic poem, all laced with references to works ranging from Orson Welles’s claustrophobic Macbeth (the beginning of the prologue) to Pieter Brueghel’s spacious Slaughter of the Innocents (at the end of the prologue) and incorporating romantic touchstones from Potemkin (a stone lion), The Lusty Men (hidden possessions), Chimes at Midnight (thrusts and counterthrusts), and The Shanghai Gesture (prostitutes in hanging cages).

Scorsese once described his concept of the film as a western set on Mars, which adds two more playgrounds to the above list and helps explain the kind of historical fantasy he had in mind. I know little about New York’s early history, yet I was impressed by how thoroughly he wanted to steep me in its otherness. Read more

An unusually clever and shrewdly corrupt first feature (1999) by English stage director Sam Mendes and writer Alan Ball, this deftly juggles satire about contemporary consumerist America (sexual obsession, gun worship, working out, capitalism) and fanciful wish fulfillment in the duplicitous Hollywood manner of The Graduate and Risky Business. Kevin Spacey, at his best, plays the disgruntled hero whose lust for his teenage daughter’s best friend (Mena Suvari) gives him a new lease on life; Annette Bening does her best with the more caricatured part of his shrewish wife. But the moral heroes here are their teenage daughter (Thora Birch) and her weird and secretive next-door neighbor (Wes Bentley), both thoroughly and understandably disgusted with the adult world. Mendes uses the superlative cinematography of Conrad Hall to excellent advantage, has a sharp sense for how to employ pop music, and moves back and forth between reality and fantasy without missing a beat; Ball has an uncanny ability to make disparate characters suddenly rhyme with one another. With Chris Cooper and Peter Gallagher. R, 121 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

Written for the FIPRESCI web site from the 33rd Toronto International Film Festival in September 2008. — J.R.

The continuing mythological status of Orson Welles in the realm of cinephilia complicates the challenge of representing Welles on film in many different ways. It’s one of the clearest merits of Richard Linklater’s Me and Orson Welles, which premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival, to have met and grappled responsibly with many if not all of the issues of this formidable challenge.

Working uncharacteristically with a script written by others — Holly Gent Palmo and Vince Palmo, adapting a novel by Robert Kaplow that I haven’t yet read — Linklater tells the story of a fictional high school teenager (played by Zac Efron, best known for his role as Link Larkin in the recent remake of Hairspray) in 1937 who by sheer chance lands a bit part as a lute player in Welles’s famous stage production of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, a highly edited modern-dress adaptation known as Caesar built around the conceit of the story taking place in contemporary fascist Italy, with a bare set illuminated by “Nuremburg” lighting. Linklater has obviously researched existing records of this production (which include photographs, a script published some years ago by Welles scholar Richard France, and at least two audio recordings of the play performed by essentially the same cast around the same time) in considerable detail.

Read more

From the November 17, 2000 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

When I spent a day in Brisbane four years ago, it struck me in terms of climate as well as social ambience as being the Mississippi or Louisiana of Australia. That’s only one of the reasons why this grim, passionate, and graphic love story about two highly dysfunctional young individuals — a chain-smoking asthmatic (Peter Fenton) and an irritable, promiscuous, and possibly crazy victim of eczema (Sacha Horler), both unemployed — reminds me of the tale about a doomed couple that forms half of William Faulkner’s The Wild Palms. Another reason is the uncanny way that Andrew McGahan, adapting his own best-selling novel, director John Curran, and cinematographer Dion Beebe have of making their story paradoxically superromantic by keeping it so doggedly antiromantic. With its honesty about sexual inadequacies (his rather than hers), drugs, squalor, and compulsive behavior, this obviously isn’t a film for everyone, but you can’t accuse it of toeing the Hollywood line, and parts of it remind me of Gus Van Sant’s first three movies, before he was swallowed whole by the studios. If you’re looking for something other than the usual cheering up, check this sick puppy out (1999, 98 min.). Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 9, 1999). — J.R.

Western

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Manuel Poirier

With Sergi Lopez, Sacha Bourdo, Elisabeth Vitali, Marie Matheron, and Basile Sieouka.

The other day I received an E-mail from someone wanting to know how I could have described The Tree of Wooden Clogs as Marxist when it was so clearly a religious film. Actually Dave Kehr had written the capsule review of Ermanno Olmi’s feature 14 years ago, but I hastily E-mailed back that any Italian could tell you that Marxism can easily be seen as a form of religion. Afterward I realized that this response was flip. It would have been better to say that Catholicism and Marxism have had a long and complex coexistence in Italy, and that it was unrealistic to expect that they would be mutually exclusive as systems of belief; the career of Pier Paolo Pasolini is proof of how intimately the two can be intertwined, regardless of the contradictions involved. That led me to think about how the simple characterizations of European Marxism in this country foster such confusion. Shortly after this I happened to read Andre Bazin’s description of The Bicycle Thief as one of the great communist films — an aspect of the film I suspect couldn’t have been apparent to American audiences when it won the Oscar for best foreign film in 1949. Read more