From the December 6, 1991 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

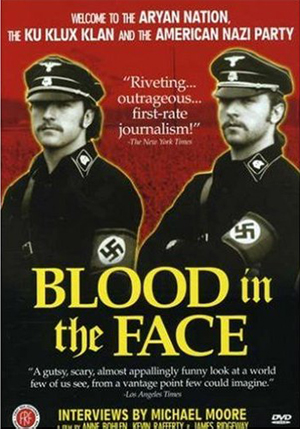

BLOOD IN THE FACE

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Anne Bohlen, Kevin Rafferty, and James Ridgeway

If memory serves, it was around my junior year in college, during the mid-60s, when a conservative classmate took my brother and me to a John Birch Society meeting in Hyde Park, New York, held inside a trailer in a trailer camp. The friend advised us to conceal our identities as liberal Jews (he was half Jewish himself) and try to blend in with the surroundings, which we did.

It was a sparsely attended meeting. Before that we made small talk with the handful of other people present — including the couple who owned the trailer and a young man who identified himself as the son of communists and who cheerfully explained that the society had deliberately adopted the structure of the Communist Party, complete with cell meetings like this one and vows of secrecy. He and everyone else in the room seemed friendly, normal everyday folks, until the film projector blew a fuse just as they began to screen a movie.

Then the paranoid speculations began: they made extensive flashlight searches of the yard around the trailer, looking for spies and saboteurs. After the fuse was replaced and the projector was started up again, the power failed a second time. Someone asked who was in charge of the local public utilities. “It’s not him,” another volunteered. “I know him pretty well, and he’s a conservative.” The meeting ended prematurely, with assurances that a thorough investigation would be made into the matter of who had sabotaged the projector.

On the ride back to campus our conservative friend — who went on to write for the National Review and teach at Harvard — was clearly delighted by their lunatic suspicions. When I met him years later in Paris, he took a similarly Mencken-like pleasure in reading aloud lengthy extracts from the Playboy interview with John Wayne, which contained such nuggets as “I’ve directed two pictures and I gave the blacks their proper position. I had a black slave in The Alamo, and I had a correct number of blacks in The Green Berets” and “Our so-called stealing of this country from [the Indians] was just a matter of survival. There were great numbers of people who needed new land, and the Indians were selfishly trying to keep it for themselves.”

I haven’t seen this friend in 20 years, but I’ll bet he’d get an enormous laugh out of Blood in the Face, a documentary about members of the American Nazi Party, the Ku Klux Klan, and the Aryan Nations. I found the film compellingly watchable myself, though probably not for the same reasons he would. The paranoid lunacy captured by filmmakers Anne Bohlen, Kevin Rafferty, and James Ridgeway is light years beyond the idle fancies of the Birchers I met or the dim complacencies of John Wayne. These are people who believe that Jerry Falwell is a Jew (existentially if not racially), that Ronald Reagan is a dupe of the Jewish conspiracy, that not one single Jew was gassed during World War II, and that Russian tanks are currently lined up across the Mexican border waiting to make their move. But the impulse to find these people hilarious, as my onetime friend might, or simply terrifying, as many others might, was not what kept me fascinated.

Laughing at these groups, I think, dismisses them too easily, while recoiling in terror gives them too much credence. (Paranoia, we must remember, is even more contagious than sexually transmitted diseases.) Caught between these extremes, I found myself agape at how much like the rest of us these people are, only more so. What they say may boggle our minds, but it’s clear that what we say boggles their minds — and considering that our statements have a much wider circulation, at least in the mass media, that’s a lot of mind boggling to reckon with. And since they appear to be every bit as confident in their beliefs as we are in ours, the alienation that we automatically feel from them registers at odd moments as the mirror image of the alienation they must feel from us.

Us and them: it’s the division felt in most war movies, horror movies, action movies, westerns. What’s interesting about Blood in the Face is that this division is all that’s being talked about on the screen, but we never see it even once in the contemporary footage that makes up most of the film. All that we see there is harmony and homogeneity: like-minded individuals agreeing with one another and enjoying each other’s company, unchallenged by the semivisible and semiaudible filmmakers who are basically content to record whatever they see and hear.

Since the filmmakers intercut quite freely between at least three distinct groups — American Nazis, Ku Klux Klan members, and Aryan Nations supporters — I couldn’t tell whether the apparent agreements between these constituencies were real or fictions partly created by (or for) this film. I also resented seeing some of the speeches and comments reduced to sound bites rather than more sustained presentations. Isn’t lumping all these malcontents together into a composite stew of xenophobic bile, crackpot theorizing, and apocalyptic fervor a little bit similar to the way these groups view everyone else?

I hoped that many of the questions raised by this film would be answered by Ridgeway’s book of the same title, published last year, which I looked at after I saw the movie. The book’s most significant clarification of the film comes in the middle of a discussion of Robert Miles, a onetime George Wallace supporter and former Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan who’s currently a Michigan pastor and leader of the racist right and is prominently featured in the film:

“During the 1980s Miles’s Cohoctah farm, not far from Flint, Michigan, became a meeting place for different factions of the far right, among which Miles sought to promote unity. At one three-day meeting in April 1986, for example, perhaps 200 people showed up. They included such leaders as Glenn Miller of the White Patriot Party from North Carolina; Thom Robb, the Christian Identity preacher who was also national chaplain for the KKK; Debbie Mathews, widow of the martyred Order leader Bob Mathews; William Pierce, author of the Turner Diaries; and Don Black, the Alabama Klansman who had been imprisoned for conspiracy to invade the Caribbean island of Dominica, and who was then running for the U.S. Senate in his state’s Republican primary. Representatives from Canada’s racist organizations, including John Ross Taylor, head of the fascist Western Guard, also made speeches.

“Participants at this gathering listened to talks on the history of the movement, tedious harangues against Jews, blacks, and other ‘mud people,’ and even a report on Satanic ritual murders. Events culminated in a cross burning on the back lot of the farm. Garbed in a Scottish kilt Miles held forth, acting as master of ceremonies and officiating as minister at a Klan marriage conducted by flashlight under the smoldering cross. He was also an indomitable advocate of an out-trek to the Pacific Northwest, where Aryans could set up an all-white homeland. Throughout, Miles did his best to broker competition among different groups, sternly advising everyone not to carry firearms, and warning the gathering to take care that their cars weren’t pockmarked by the fire from the cross burning, and to beware of the press.”

Apparently not all of the press: barring only a few details (among them those contained in the final sentence), these two paragraphs effectively summarize Blood in the Face: clearly all or virtually all of the film’s contemporary footage comes from the three-day gathering in 1986. That’s an important fact, and I can’t understand why the filmmakers chose to omit it — or at least obscure it by giving no date or any other clear indication of setting (except for one early title, “Cohacio, Michigan”). I can understand their decision to exclude voice-overs and to minimize explanatory titles, but surely some knowledge about the context of the event — including a clear understanding that it was a single event — is essential if we want to read the film as anything more than a parade of exotic zoo animals. (There are some archival clips interspersed with the contemporary footage. These mainly show George Lincoln Rockwell, founder of the American Nazi Party; a woman who witnessed his assassination; German Nazis; familiar shots of concentration-camp corpses being dumped into graves; the aforementioned Bob Mathews; the murdered radio talk-show host Alan Berg; and David Duke campaigning in Louisiana in 1989.) We get one hint of how the film came to be made toward the end, when Miles addresses the filmmakers: “We invited you here so that we could use you just the same way that you were using us.”

Theoretically two antithetical charges can be made against the film — and I’ve heard that both of them were made when Blood in the Face was shown earlier this year at the Blacklight film festival. One, it provides a forum to a lot of dangerous people, and two, it’s been edited in such a way that the groups’ least intelligent and informed speakers monopolize the proceedings.

I have no way of judging the accuracy of the second charge, though it is true that the filmmakers occasionally resort to manipulative editing (in the manner of Roger and Me‘s Michael Moore, who receives an acknowledgment in the final credits) in order to undercut what someone is saying. After a woman argues that racial separatism is virtually the same thing as trying to save whales and seals, adding that “Animals stay to their own species,” there’s a cut to two dogs of separate breeds sexually frolicking.

Undoubtedly Ridgeway’s book has its uses, but it seems to share with the movie a debilitating breeziness. (The book includes some information about the John Birch Society, for instance, but not a clue about its current status. One chart shows the society continuing into the present, but all discussion of it is in the past tense.) One reason the film’s absence of context is so damaging is that it’s almost impossible to gauge how heterogeneous these separate hate groups are. After all, they’ve been brought together for an event specifically designed to unify them — an event, in other words, partially conceived for purposes of propaganda. People who describe Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will as an “objective” documentary of a Nazi rally (including Riefenstahl herself) are conveniently ignoring the fact that the rally was convened so that a film could be made of it. (We even discover from Albert Speer’s memoirs that studio retakes were made of certain speeches.) I’m not trying to suggest that Blood in the Face is at quite this level of premeditation, but I wish that Miles’s agenda and the filmmakers’ agenda — including information about how this film came to be made — were more precisely spelled out.

Certain details definitely throw the supposed homogeneity of the groups into question. The film opens with the camera drifting past many people standing casually on a lawn outside a meeting hall, eventually identified by an impromptu sign as Hall of the Giants. (“Giant” is Klanspeak for “head of a province.”) But giants aren’t exactly what we see. We notice two men in Scottish kilts, one in army fatigues, many with Nazi arm bands, some in suits, and some in jeans. We hear the voices of a few kids, but the only woman we see is walking away from the gathering; when we cut to the beginning of the meeting inside, however, a few more women are visible. Next we get snippets from seven separate talks, then the discourse continues in casual statements made over lunch at a picnic table outside, and here the lack of homogeneity is striking: though all of the people seem to be working-class — a fact underlined immediately afterward, first by Miles and then by five uniformed American Nazis, one of them female — it’s equally striking that one speaks with a pronounced European accent and that none, with the possible exception of the uniformed woman, conforms to the Nordic specimens we associate with Hitler’s Nazi rallies. They’re merely unglamorous Americans who feel disenfranchised, just like most of the rest of us.

“Can it be that everybody is looking for a way to fit in?” Harold Rosenberg asked in his book The Tradition of the New. “If so, doesn’t that imply that nobody fits?

“Perhaps it is not possible to fit into American life. American Life is a billboard; individual life in the U.S. includes something nameless that takes place in the weeds behind it.”

The hatred and paranoia we witness in Blood in the Face are certainly disquieting, but they’re also familiar, and far from exclusive to members of so-called hate groups. I have to admit that I’ve occasionally felt these things myself, some of it directed against people like the people in this film. (Why else did I sneak into that John Birch Society meeting, and why else did they perceive that spies might be in their midst?)

In a curious way, feelings of this sort are a substantial part of what people in this country hold in common, but because the targets are different, they lead to warring tribes, as well as to coalitions of the sort in this film. Sometimes I wonder which of the two is worse — the coalitions that make wars possible, or the wars that make coalitions necessary. During the confirmation hearings of Clarence Thomas, the whole country seemed to be going through a fresh version of this tortured factionalism (or “fractionalism”), which repeatedly splits us apart — whether one believed Thomas or Anita Hill, the anxiety and despair were the same.

I can recall once hearing a radio interview with George Lincoln Rockwell, probably when I was in my teens. The interviewer was the late Joe Pyne — an early example of the hate-filled talk-show host who’s become so much a symbol of our times (see Talk Radio and The Fisher King) — and he was so vicious and rude throughout the program that I found myself, perversely, sympathizing more with Rockwell. In the final analysis they were both monsters, but the fact that Pyne could elicit this response from me has made me wonder ever since whether expressions of hatred can obliterate moral distinctions of any kind.

The title Blood in the Face comes from one of the racist statements made in the film, that you can’t trust anyone you can’t see blushing. Before I realized what the source of the title was, I’d assumed a more violent meaning, as in “blood on the face,” and I wouldn’t be surprised to hear that many others have made the same assumption. That suggests that the violence we automatically bring to this material — emotional as well as polemical — is fully commensurate with the violence directed back at us.