From the Chicago Reader (April 6, 2001). This is also reprinted in my collection Essential Cinema.— J.R.

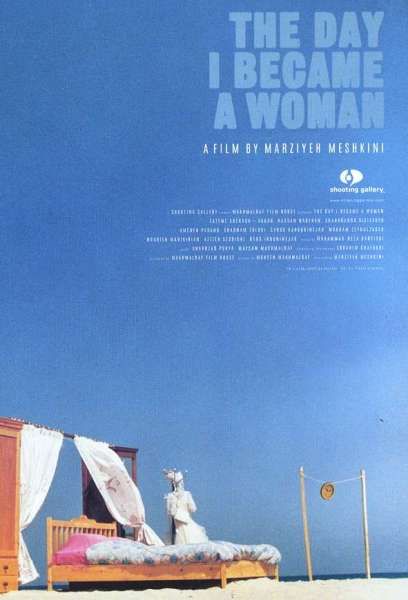

The Day I Became a Woman

***

Directed by Marzieh Meshkini

Written by Mohsen Makhmalbaf

With Fatemeh Cheragh Akhtar, Hassan Nabehan, Shabnam Toloui, Cyrus Kahouri Nejad, Azizeh Seddighi, and Badr Irouni Nejad.

“Aren’t you afraid?” some of my stateside friends asked before I visited Iran for the first time last February. “Only of American bombs,” I replied. Notwithstanding all of the things that are currently illegal there — such as men and women shaking hands or riding in the same sections of buses — I’m not sure I’ve ever been anyplace where people display more social sophistication in terms of hospitality, everyday courtesy, or sheer enterprise in the use of charm and persistence to get what they want. Some of this character came through in Divorce Iranian Style, a fascinating documentary that turned up at the Film Center a couple of years ago showing the aggressive resourcefulness of Iranian women in divorce court, despite the repressive laws they have to work with.

The locals I spoke to tended to be pessimistic about the reformist movement — regarding Mohammad Khatami about as skeptically as American liberals regarded Bill Clinton during his last year in office — but it also quickly became clear that some aspects of Iranian life are not defined by Islamic fundamentalism and that what might seem hopeless in one context might be possible in another. Behind closed doors, things often turn out to be freer than one might imagine, especially for people who have money.

***

On the northern tip of Tehran is a mountain that was still snowcapped in February, and when the sun was out, melted snow ran down gutters in the city below like rushing mountain streams. Well-off people live on the mountain, and two Iranian filmmakers I visited, Abbas Kiarostami and Darhius Mehrjui, were on the side facing south. Another filmmaker, Bahman Farmanara, was on the side facing north, and getting from Kiarostami’s office to Farmanara’s house entailed driving along parts of the route traversed in Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry. I wasn’t surprised to find that Mohsen Makhmalbaf hasn’t put the Makhmalbaf Film House on the mountain. For all his enormous success, Makhmalbaf remains in some respects a working-class hero in Iran, and his fundamentalist background serves as a reminder of how far he has traveled.

The credits for The Day I Became a Woman, opening this week at Landmark’s Century Centre, list Makhmalbaf as writer and his young wife, Marzieh Meshkini, as director. In the press book he writes, “Five years ago, while I had been the most prolific Iranian filmmaker, with 14 feature films, 3 shorts, 28 books, and 22 editing credits over a 14-year career, I stopped making films and decided to make filmmakers. I started the Makhmalbaf Film House with only eight students selected among family and friends.

“After four years, the school graduated a cameraperson, a sound recordist, an art director, three directors, and an editor/photographer. During the course of their studies, my students also produced several films as their school projects, including The Day I Became a Woman by Marzieh, my wife, [and] The Apple and Blackboards by Samira, my daughter.”

Some Western commentators have scoffed at Makhmalbaf’s claims, maintaining that he’s the real director of these three films and that his time would be better spent owning up to his auteur status. This position is not only dead wrong, but it smacks of ethnocentric, sexist, and imperialistic complacency. Insofar as contemporary Iranian art cinema can be split into two schools — one associated with Makhmalbaf, the other with Kiarostami — they’re separated by, among other things, their relation to auteurism. (They’re also separated by their relation to the written word: Makhmalbaf started out as a playwright and has published the scripts of many of his films, including the one for The Cyclist that we see his impersonator carrying on a bus in Kiarostami’s Close-up; Kiarostami started out as a graphic artist and hasn’t used scripts on any of his films for several years.) Despite personal details in the scripts of such films as The Peddler, The Actor, and A Moment of Innocence and his appearance in Salaam Cinema, Makhmalbaf can’t be said to possess a single directorial style of his own, not even an evolving one. His films are held together by a social mission, not by a style of mise en scène or a style of filming or editing — in fact, he has often created pastiches of other directorial styles, most obviously that of Sergei Paradjanov in Gabbeh.

Furthermore, The Apple and Blackboards, though both scripted by Makhmalbaf, are centrally about community, which can’t be said of any of Makhmalbaf’s films as a director. We also know from his wife that he provided only the outlines of the three sketches in The Day I Became a Woman, whereas she wrote the dialogue, developed the characters, and prepared the shooting script. And while she was directing that film, he was shooting a picture of his own — “Testing Democracy,” which forms half of the feature Tales of an Island — albeit on the same island where Meshkini’s feature was being shot. One could probably find auteurist parallels between The Day I Became a Woman and Makhmalbaf’s 1987 feature of three sketches, The Peddler, but that seems a particularly dull and unproductive exercise, one that flatters American conceits about individualism at the expense of Iranian notions of collectivity. Why insist on treating good baba ghannouge as if it were bad peanut butter?

***

Kish Island, located in southern Iran, is, according to the Lonely Planet guide to Iran, “a bizarre place: a little bit of Singapore with highways and towering apartment blocks and hotels; a quasi-Disneyland with theme parks; and a poor man’s California with beaches and bicycle paths — all with a unique Iranian style. The main attraction for Iranians, however, is the availability of duty-free electrical goods.” The beaches are relevant to all three sketches of The Day I Became a Woman, the bicycle paths are relevant to the second, and the highways, theme-park ambiance, and electrical goods are relevant to the third. And everything looks gorgeous.

***

The Day I Became a Woman presents three allegories about being a woman at three separate stages of life: childhood, young motherhood, and old age.

Havva (Persian for “Eve”), who lives with her mother near the beach, is the heroine of the first story. It’s the morning of the day when she turns nine — which in Iran is the day she becomes a woman — and this means she can no longer play with boys, specifically with her friend Hassan. But once it’s established that she doesn’t turn nine until noon, an hour away, she’s allowed to run off until then. She finds that Hassan has been grounded by his sister until he finishes his homework, and she returns a little later with sour tamarind pulp and a lollipop, both of which she shares with him, putting each in his mouth for brief intervals. (According to Meshkini, the Iranian censors wanted to cut the shared lollipop, which they found too erotic; she stood her ground, and the film has already played commercially in Iran without cuts.)

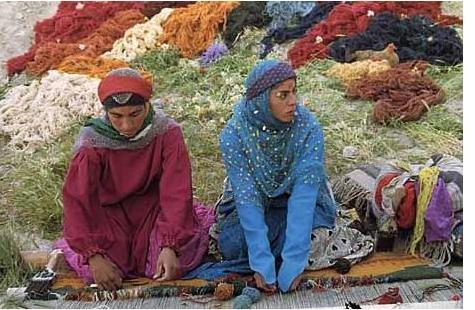

The second heroine, Ahoo (Persian for “deer”), is part of a large group of women in chadors pedaling bicycles down a highway that runs parallel to the Persian Gulf. Her husband, uncles, and other male in-laws and the male elders of her clan all chase after her on horses, demanding that she stop her nonsense and return to family life, but she keeps charging ahead; the end of this sketch is deliberately unclear about whether they manage to stop her or not. Again according to Meshkini, Kish Island has the only bicycle path in Iran and is “the only place women can ride bicycles freely” — it’s forbidden for them to do so in Tehran. (Makhmalbaf’s utopian film school — which generally focuses on one or two topics per month, many relating not merely to film but to sports, philosophy, business, and the arts in general — once devoted eight hours a day to skating and bicycling, so one wonders if the female students had to break the law to participate.)

The third heroine, the elderly Houra (Persian for “nymph”), arrives on the island in a wheelchair and hires a local boy to cart her around to shops in the local malls; thanks to a recent inheritance, she has the means to get what she’s always wanted–furniture as well as appliances — and has tied colored strings around each of her fingers to remind her of what she wants. After depositing all of her goods on the beach, she returns to the malls in hopes of remembering the only item that’s skipped her mind, while the boys in the vicinity unpack her goods, install them as if in a living room, and fool around with them. Houra returns around the time that a couple of the women bicyclists and Havva, now dressed in a chador, turn up to watch her leave — along with her goods, which the boys push out to sea on rafts.

***

The first story is the most realistic, the second is the most visceral — a sequence in giddy perpetual motion, as brilliantly polished as the Steadicam accompanying the little boy’s toy car through the Overlook Hotel in The Shining — and the third is the most surrealistic. All three heroines are extremely stubborn and know exactly what they want to do, but the only one pursued and confounded by grown men is Ahoo. By contrast, Havva and Houra are surrounded by boys, who set out to sea at the end of each segment, with or without the heroine; and to all appearances, Havva is pursued and confounded only by grown women.

Meshkini has said both that she doesn’t consider herself a feminist and that she believes in equal rights for women — a kind of double-talk that seems frequent and perhaps even necessary in contemporary Iran. (Similarly, Jafar Panahi has claimed that his much more radical feature The Circle — a masterpiece that has yet to show in Iran, though it’s coming to the Music Box in June — isn’t even political.) Meshkini’s unidentified interviewer in the press book notes that in the first story, “the girl loses her freedom; in the second, she is trying to regain it; and in the third, she has it but it is too late for her to do much with it.” In response, Meshkini speculates that what Havva loses may be her childhood rather than her freedom.

Whatever she loses, the story conveys a keen sense of loss — one that brought me back to a moment in my own early grammar-school days when, simply because of my age, I seemed to lose the option of being friends with girls; when my best friend, Helen, and I proposed spending the night together, both of our mothers were scandalized. The second story, at least before its ambiguous ending, conveys a sense of release that’s equally sharp. The third story is by all counts the funniest, but it has its sad aspects too; the old woman keeps trying, without success, to adopt the boys she hires, and her rampant consumerism makes this episode the most “modern” and the most American in the trio — it’s like a hallucinatory vision of Miami that overlaps exteriors and interiors.

I’ve been told that Iranians can be just as color conscious as Americans, so there’s some reason to observe that most of the boys in this movie are black and that Havva herself is fairly dark skinned — hints that there’s an underclass in Iran and maybe that being black and being female are two versions of the same thing. The stories are simple enough, but they’re also poetic in their resonance — intended to make an imprint on our dreams as well as our thoughts.