Written for the July-August 2017 Film Comment. This is the unedited version of my review. — J.R.

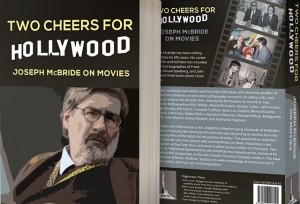

Two Cheers for Hollywood: Joseph McBride on Movies

By Joseph McBride, Hightower Press, $38.50.

Anyone who’s read his astute critical biographies of Capra, Ford, Spielberg, and Welles knows that Joseph McBride is one of our most invaluable film historians. No less ambitious but more personal are his three most recent books, all brought out expertly under his own imprint and available from Amazon: his hefty Into the Nightmare: My Search for the Killers of President John F. Kennedy and Officer J. D. Tippit (2013), his very moving and painfully candid The Broken Places: A Memoir (2015), and now an even heftier volume collecting half a century’s worth of his film journalism and criticism, encompassing 56 separate items and almost 700 large-format pages. It’s the sort of old-fashioned bedside compendium and browser’s paradise that we seldom get nowadays from academic publishers—with a few rare exceptions, such as Greil Marcus and Werner Sollors’ delightful 2009 New Literary History of America (which included one of the better McBride essays reprinted here, “The Screenplay as Genre,” about Citizen Kane). McBride prefaces each piece with a contextualizing introduction, and part of what makes this volume fun is the informal history it offers of McBride’s own taste and career.

McBride’s title derives from E.M. Forster’s 1951 collection Two Cheers for Democracy and his essay “What I Believe”, which declares, “Two cheers for Democracy: one because it admits variety and two because it permits criticism. Two cheers are quite enough: there is no occasion to give them three.” McBride served for three separate stints as a reporter for Variety (1974-77, 1980-81, and 1989-92), the last of which ended after Paramount threatened to remove its advertising because of McBride’s review of Patriot Games describing it as a “fascistic cartoon” (McBride’s paraphrase), and clearly he owes much of his ambivalence about Hollywood to his training as an industry reporter. Despite his uncharacteristic credentials as a leftist auteurist, he’s still enough of a mainstream player in the Oscar-strewn Hollywood game to regard Shane as his favorite Western.

Among the highpoints are his sensibly reasoned (if guarded) defense of the Coen brothers; a detailed historical account of Welles’s Too Much Johnson; revealing interviews with Billy Wilder, Stepin Fetchit, Richard Lester, François Truffaut, and The Three Stooges’ preferred director, Edward L. Bernds; visits to the sets of Family Plot and The Shootist; discerning thoughts about both Steven Spieberg’s mixed critical reputation and his “strange partnership” with Joe Dante. In the two cheers department, I would cite his excellent appreciation of his (and my) favorite Elia Kazan film, Wild River, coupled with his more debatable claim that “Kazan’s work as an artist improved” after he informed on his colleagues. (This is defensible up to a point, and McBride’s intellectual honesty in making such a case is admirable. but I personally find Panic in the Street far more nuanced than The Visitors.) Furthermore, the unsubstantiated claim that “Buddy Buddy resembles a work of Samuel Beckett” sounds as unwarranted as his supposition that the derisive reception of Truffaut’s underrated Fahrenheit 451 in 1966 in Madison, Wisconsin was “representative of the reception the film was given around the world”. (He supposes wrong: it was received quite respectfully by the New York and London audiences I saw it with.)

There’s an unfunny 1976 parody of various film reviewers done for American Film, and a sour 1970 interview with Godard during his worst period, redeemed only by McBride’s contemporary effort to make sense of Godard today (unlike, say, Owen Gleiberman’s flounderings in his review of Redoutable in today’s Variety). But these are infrequent glitches in an anthology of very intelligent grapplings, encounters, and reflections, full of lasting insights.