I’d completely forgotten about my having written this piece until I came across it recently here, complete with the photo of me (apparently in late 1999) delivering this paper at a panel discussion in Chicago. Apart from correcting a few typos and adding some other photos, I’ve reproduced it here more or less as I found it. (Afterword, April 2, 2015: I’ve done a light edit on this.) — J.R.

It’s tempting but dangerous to approach artists from exotic cultures in terms of more familiar reference points such as comparing Zhang Yimou’s Ju Dou to The Postman Always Rings Twice or reading Souleymane Cissé’s Brightness as if it were an African Star Wars, as some American and English critics have done. Yet to describe the styles and visions of the two major Iranian filmmakers of the Eighties and Nineties, Abbas Kiarostami and Mohsen Makhmalbaf, I’ve been exploring comparisons to Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoevsky — a project obviously fraught with booby traps, but one that none the less clarifies some of the important differences between these two major figures.

A key difference which has only an oblique relevance to my comparison is that Makhmalbaf has been the most popular and respected filmmaker in Iran in recent years, despite his many run-ins with state censors, while Kiarostami is a hero principally elsewhere. Within Iranian society Kiarostami is widely regarded and in some cases resented as a self-serving pet of Western critics.

Though he came from a middle-class (albeit financially insecure) family, Dostoevsky, whose first novel was entitled Poor Folk, called himself an intellectual proletarian, and an identification with society’s lower strata is clearly central to his work, as it is to Makhmalbaf’s. A key traumatic event that shaped Dostoevsky’s future work was his arrest at age 27 for radical anti-government activities (during the repressive reign of Czar Nicholas II) and his subsequent sentencing to death by a firing squad. This sentence was commuted at the last moment, and Dostoevsky wound up with four years of hard labor in Siberia followed by four years of military service as an alternative sentence. But his belief that he was about to die left a permanent mark on his style and vision.

Something comparable happened to Makhmalbaf, a working-class fundamentalist and terrorist fighting the shah’s regime when he was arrested and tortured at the age of 17. Apparently it was only his youth that saved him from the firing squad; he wound up serving a five-year prison term that ended only with the 1979 revolution. Judging from a text by Makhmalbaf recently published in English that appears to be semi-autobiographical, he fully expected to be killed during the early stages of his incarceration.

The incident that led to his arrest — Makhmalbaf stabbed a policeman with a knife — is the focus of A Moment of Innocence (1995), one of his finest features. One sign of his change over 22 years is that the policeman he stabbed is invited to help recreate the event (as an unofficial, on-screen co-director who coaches the actor playing him) and show what he was going through at the time. A fictionalized version of Makhmalbaf’s arrest, torture, and stint in prison is the focus of Boycott (1985), and it’s no less telling that this film ends with its hero’s execution.

Comparing Kiarostami to Tolstoy involves a much looser set of analogies. For starters, Kiarostami hails from the upper-middle-class, not the cultured gentry, and his cautious distance from Islamic fundamentalism throughout his career has nothing in common with Tolstoy’s belated, fervent Christianity. Indeed, the physicality, serenity and cosmic overviews of both artists in contrast to what might be termed the tormented psychological and spiritual views of Dostoevsky and Makhmalbaf may constitute the sum of their shared traits. They’re both masters of framing landscapes and vistas in contemplative long shots, while Makhmalbaf and Dostoevsky are expressionist sketch artists exposing the cramped and conflicted interiors of their own brains in staccato flashes of lightning. Otherwise Tolstoy and Kiarostami seem to share common ground mainly in contrast with the nervous, twitchy, and hysterical styles of Dostoevsky and Makhmalbaf and the comparable behavior of many of their characters, although this is somewhat less true in the most recent work of both filmmakers.

When I took a course devoted to the two Russian authors in college, the class was split between partisans of each; I can’t recall anyone apart from the teacher who expressed equal fidelity to both. I belonged to the Tolstoy camp, and if I reread both writers today I’d probably feel the same. I also feel closer to Kiarostami than to Makhmalbaf, maybe because my background is closer to his. But much as I suspect that Dostoevsky has more to say about Russian culture than a universalist like Tolstoy I’m fairly certain that it’s Makhmalbaf, not Kiarostami, who has the most to teach me about Iranian culture, particularly over the past quarter of a century .

Apart from growing up poor, Makhmalbaf was an unwanted child, as we learn from Houshang Golmakani’s documentary Stardust-Stricken: Mohsen Makhmalbaf — A Portrait (1996); he was essentially raised by his grandmother, whom he later had to support and care for. (This experience inspired the middle episode of his three-part feature The Peddler about a scatterbrained, spastic, and persecuted Jerry Lewis-type whose life is devoted to caring for his aged and senile mother.) After he emerged from prison he returned to political activism for a short spell, then helped to establish a group of artists known as The Islamic Propaganda Organization and became a prolific writer of plays, essays, short stories, and eventually screenplays. One early monograph — a good indication of how far he has traveled ideologically since then — propounded a fundamentalist argument against women appearing onstage. His first screenplay to be realized (by someone else) was The Explanation (1981), and he directed his first feature the following year. Reportedly neither of his first two features, both marked by didactic Islamic propaganda, had much of a public impact.

I am told that Makhmalbaf now dislikes Fleeing From Evil To God (1984) and Boycott, his third and fourth features, and agreed to include them in a touring retrospective only after recutting them. The first is by all counts the worst of his films I’ve seen, bad on just about every level –- acting, mise en scene, script, and overall conception. But its evident sincerity combined with its naivete is undeniably fascinating, because I’ve never seen anything else like it; its rough American equivalent might be a painting of Jesus in the wilderness executed by an illiterate farmer. The only Makhmalbaf movie I’ve seen in a Scope format, it follows five nameless religious men, all dressed like monks, on a desert island as they flee from the devil’s temptations. The opening music calls to mind a spaghetti western, but very little happens in the film; the action consists mainly of metaphysical speculation spelled out in allegorical terms, not any struggle with evil or Satan in the real world.

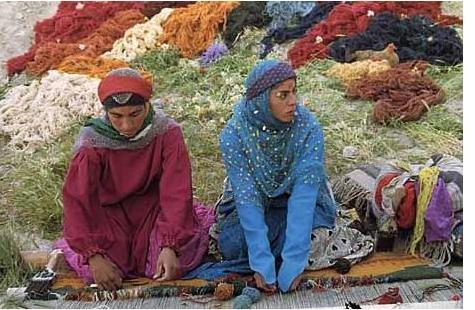

No two Makhmalbaf films are alike. Moving from film to film, one sees a mercurial, troubled intelligence constantly seizing upon new stylistic influences, often seeming at odds with itself within individual features -– although there’s more self-acceptance in such recent work as A Moment of Innocence, Gabbeh, (1996), and The Silence (1997), not to mention his daughter Samira’s wonderful feature The Apple (1998), which he scripted and edited. But it’s still a shock to pass from a strained amateur exercise like Fleeing From Evil To God to the skillful and frenetic Boycott, which abounds in Hollywood-style action sequences (including a shoot-out, a prison escape, and an adroit car chase), goofy and upsetting subjective moments (such as the hero’s nightmare of ants devouring his face and animated ants in a later sequence), and apparently unmotivated freeze-frames tossed in the middle of a prison riot. The film clearly charts Makhmalbaf’s disillusionment with politics: “I used to fight because I existed,” the protagonist says in an early scene, after his arrest. “Now I no longer exist.” (Much later, he dryly notes that “imperialism and socialism are the same to a corpse” to a communist fellow prisoner bent on turning him into a Marxist martyr.) It also shows a growing commitment to popular film making; as a fundamentalist youth, he was so opposed to cinema that he once refused to speak to his grandmother for several days after she went to the movies. (Apparently he now dislikes Boycott for its commercialism and has similar objections to The Actor, made eight years later, a box-office hit in Iran.)

In the April, 1997 issue of Sight and Sound, Houdini Ditmars reports Makhmalbaf saying that the best Iranian films came from the 1985-90 period, when censorship was at a low ebb. Considering the output of both Makhmalbaf and Kiarostami during those six years, it’s a thesis well worth considering. During this stretch Kiarostami made The First-Graders, Where Is The Friends House?, Homework, and Close-Up; Makhmalbaf made Boycott, The Peddler, The Cyclist, Marriage of the Blessed, Time of Love, and The Nights of Zayandeh Road. The last two pictures were promptly banned, and Time of Love, a three-part theme-and-variations about adultery shot in Turkey with Turkish actors, seems a relatively minor work (albeit a thoughtful and provocative one). But the preceding three pictures may well represent Makhmalbaf’s most important achievements to date , apart from A Matter of Innocence.

All three are troubled, lyrical arias about human suffering in contemporary Iran that attack social problems — urban squalor, social cruelty and crime in The Peddler; capitalist exploitation in The Cyclist; the nervous condition of a traumatized veteran of the Iran-Iraq war in Marriage of the Blessed — with an unrelenting hallucinatory fury. All three pictures, like Boycott, are somewhat out of control, but as with Dostoevsky in novels like The Idiot, it’s when Makhmalbaf is most out of control that he seems to cover the widest emotional and poetic range of material in the everyday world. Rather like Martin Scorsese wrestling with the demons and contradictions of his childhood Catholicism, Makhmalbaf seems to be fighting with new versions of his skeptical, evolving intelligence in every project. Makhmalbaf has noted that a major difference between Iranian and Western cinema is that “in the West, the evolution of cinema began with paintings, then photography… it was a progression through image.. But in the East, our tradition of the Persian miniature did not really affect our cinema. At the beginning of the Islamic era, paintings and drawings were discouraged. So our tradition of image is not as old as our tradition of poetry… [and] we went straight from narrative to cinema… Our story-telling tradition is very poetic.”

How does Makhmalbaf’s visual style reflect this alternative tradition? Largely, it seems, through its eclectic editing and framing, including frequent recourse to what Western viewers regard as eccentric camera angles. These angles are especially apparent in Boycott, The Peddler, The Cyclist, Marriage of the Blessed, and The Actor and what seems most disorienting about them is their seeming lack of motivation. This gives his scatter-shot technique a freshness combined with an overall sense of chaos: like a restlessly shifting insomniac, a typical montage leaps around a given subject with desperate abandon, as if looking for and never finding a proper resting place.

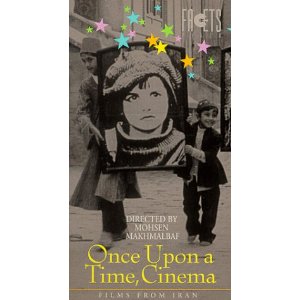

The literal meeting-point between Makhmalbaf and Kiarostami’s cinema is the latter’s masterpiece Close-Up (1990), which reenacts the trial of Ali Sabzian, the real-life impersonator of Makhmalbaf who charmed his way into a bourgeois family’s household on the pretext that he was planning a film about them. Merging documentary and fiction even when it stages a first meeting between Sabzian and Makhmalbaf in its closing sequence, this singular feature finds many echoes in Makhmalbaf’s subsequent work, first when he takes on the subject of cinema himself in Once Upon a Time, Cinema (1992) and Salaam Cinema (1994), and then when he appropriates some of Kiarostami’s methodology in A Matter of Innocence. The capsule history of Iranian cinema that ends Once Upon a Time, Cinema concludes appropriately with a shot of the zigzagging footpath on a hillside from Where Is The Friends House?, a shot that epitomizes Kiarostami’s own blend of documentary and fiction because he designed the footpath in this rural location himself.

If this implies that Makhmalbaf’s Dostoevskian interior journey has gradually taken on some of the breadth of Tolstoy’s exteriors, a complementary development can be traced in the recent work of Kiarostami, whose Taste of Cherry confronts the theme of suicide –- a quintessentially Dostoevskian subject, filmed exclusively in exteriors but concerned throughout with what might be called spiritual interiors. Indeed, the exciting recent developments of both filmmakers show the limits of any comparisons with the great Russian novelists or any other restrictive definitions. At most they offer suggestive starting points for western spectators, but the remainder of the journey needs to be taken without them.

10/24/99

Bulletin of’ The 10th Festival of Film from Iran

by Film Center of Chicago