From Monthly Film Bulletin, October 1975. — J.R.

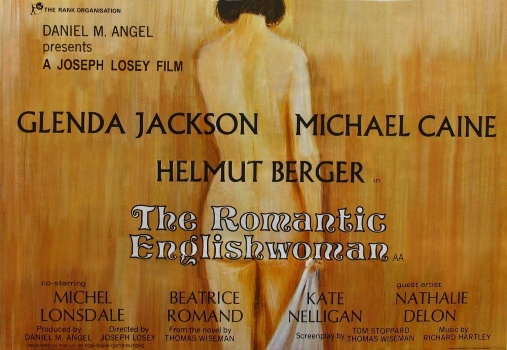

Romantic Englishwoman, The

Great Britain/France, 1975 Director: Joseph Losey

Elizabeth Fielding arrives in Baden Baden on holiday; on the

same train is Thomas Hursa, carrying a supply of drugs, which he

hides on the roof of the luxury hotel where Elizabeth is staying.

Her husband Lewis, a successful novelist now at work on a

screeinplay about a discontented woman who leaves her

husband, phones her at midnight. While Elizabeth converses

with Thomas in a lift, Lewis imagines her making love with

a man in a similar situation (an image which he uses in his

screenplay); he rings her again at 12:30 and she answers

belatedly, saying that she will be home in Weybridge the

next day. Thomas’ drug supply is destroyed in the rain

and he flees when he discovers that Swan, a drug contact, is

looking for him. When Elizabeth returns at night, she and Lewis

start to make love on their front lawn, but are interrupted by a

neighbor. After expressing his suspicion that his wife was

unfaithful in Baden Baden, Lewis receives a letter from Thomas

describing himself as a poet and admirer of Lewis’ work and

mentioning that he met Elizabeth in Baden Baden. He arrives

one afternoon for tea and stays on as a house guest at

Lewis’ insistence and despite Elizabeth’s protests. Finding

her son David on the roof one day while Thomas coaches

the au pair Catherine in her English, Elizabeth flies into a

rage, implying that the two are having an affair, and

Catherine leaves the house. When Elizabeth and Thomas go

out to dinner, he is recognized by an underworld figure and

decides to leave at once. After returning home, and being caught

by Lewis in an embrace with Thomas, Elizabeth decides to leave

with him. They travel to the Mediterranean, where Thomas resumes

his drug trade and his former work as a gigolo while only

occasionally seeing Elizabeth. He phones Lewis, who drives to the

south of France to fetch his wife, and is followed by Swan. Thomas

is finally led away by Swan, and Elizabeth returns home with Lewis,

where they find a party which they arranged beforehand in progress

in their house.

Why does Elizabeth (Glenda Jackson) go to Baden Baden? Is the

drug supply that Thomas (Helmut Berger) deals in heroin or

cocaine? Do Elizabeth and Thomas sleep together in Baden Baden?

Is the Herman with whom Lewis (Michael Caine) discusses his

screenplay a producer or director? Is the screenplay, and Lewis’

accompanying suspicions and manipulations, a response to

Elizabeth’s restlessness and behaviour, or the cause of it? Thanks to

the oddly slick and rudderless direction of an equally bantering and

unstable script, The Romantic Englishwoman tends to place all

these varied ambiguities on roughly the same level — eliciting, in the

final analysis, something closer to a shrug than any deep concern

about whether the solutions to these mysteries actually matter.

The shame of it is that the basic material might have led somewhere

fruitful: the chicken-or-egg enigma about Lewis’ suspicions of

Elizabeth’s infidelity, balanced by Elizabeth’s own suspicions of an

affair between Thomas and the au pair Catherine, could have

resulted in an intriguing treatment of the causes and effects of a

bored bourgeois imagination; and at least Joseph Losey and his

writers [Thomas Wiseman, author of the source novel, and Tom

Stoppard] go to the trouble of offering Caine and Jackson one

disproportionate and dramatically effective tirade apiece —

against Elizabeth’s friend Isabel and Catherine, respectively —

which help to underline this theme. Unfortunately, the

filmmakers’ own bourgeois imaginations seem to have become

comparably bored, and these mini-climaxes turn out to mark

the limits of the concept where they might have worked better

as a starting point. Too many assumptions about the ’emptiness’

of Elizabeth’s and Lewis’ lives are taken to be self-evident and

not worthy of exposition or elucidation, while Thomas curiously

winds up serving as a more improbable fantasy figure for the

audience — quasi-inept drug-dealing gigolo as Authentic

Existential Hero — than he does for the Fieldings. The fatal

miscalculation behind the film rests in this imbalance: when

Losey depicts Lewis’ imagined screenplay as a string of

Hollywood parodies, the implication appears to be that The

Romantic Englishwoman itself rises above such nonsense.

But from the moment we follow Elizabeth’s horse-drawn

progress through a supposedly ‘real’ Baden Baden, we are

clearly within a postcard kingdom in which Continental

drug deals and diverse upper-class revels are no less

stereotyped than the supposed fantasies. And the figure

of Thomas, bandied about like a glamorous symbol-prop,

seems to function more as an expedient plot mechanism

than as a character in his own right, which makes his

implied superiority to Elizabeth and Lewis a questionable

matter indeed. Losey’s style has always tended towards a

considerable amount of moral didacticism which has usually

depended on psychological demonstrations. The Romantic

Englishwoman keeps the didacticism while dropping most

of the demonstration, so that ‘distanciation’ from the two

central characters appears to derive mainly from a lack of

interest in them, and a copious use of window reflections and other

mirror images registers principally as window dressing. What

remains is a perfectly adequate and watchable (if romantically

routine) expression of the very milieu and sensibility that the film

professes to expose and despise.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM