From Film: The Front Line 1983 (Denver, CO: Arden Press, 1983).

Although I still agree with most of my arguments here, it’s now clear to me that my characterization of Paul Schrader’s politics in 1983 were oversimplified at best, and simply wrong at worst. — J.R.

Tenants of the house,

Thoughts of a dry brain in a dry season.

T.S. Eliot, Gerontion

Preface: When I was approached last year about inaugurating a series of volumes surveying recent avant-garde film, I immediately started to wonder about how this could be done. Having lived nearly eight years in Paris and London and about as long in New York, I’ve had several opportunities to note the relative degree of information flow between these and other centers of avant-garde film activity, and the growing isolation of New York from these other centers made my own fixed vantage point less than ideal in some ways. When a colleague told me that Jonas Mekas had recently said that it was no longer possible to know what was happening in experimental film as a whole, a bell of recognition rang in my head, and I knew at once that Mekas was the only available oracle l could turn to. The Lithuanian patron saint of the American avant-garde film, now 60, has been an American filmmaker for at least half of his life, and a chronicler of the avant-garde film in New York — mainly in The Village Voice and (more briefly) Soho News — for at least 15 years. If he no longer knew with confidence where we were, a consideration of the nature of the very problem of our ignorance was clearly in order.

Out of this need and curiosity, the two following conversations took shape, with Mekas’s kind consent, at the temporary headquarters of Anthology Film Archives on Broadway in lower Manhattan, in late July and early November 1982. Robert Haller, executive director of Anthology, was present at both discussions, and some of his remarks are also included.

The second dialogue, longer and somewhat more polemical than the first, occurred during a two-week season at the Public Theater devoted to Jean-Marie Straub and Daniele Huillet and filmmakers they admire (about two dozen films in all) that l was involved in curating at the time, and which became a logical reference point for part of our discussion. The results have been edited by Mekas as well as myself.

JR: Your own films are full of things about politics.

JM: lndirectly, everything is political; everything under the sun can be interpreted politically. But the motivations for making it are not political in that sense; they’re personal.

JR: But don’t you think that whatever uses art is put to have political consequences?

JM: Consequences, sure. With a knife you can cut bread or stab somebody in the heart.

JR: l’m disturbed about the way that an extreme right-winger like Paul Schrader can accommodate Michael Snow’s films to his own social philosophy.

JM: Do you think you can make a film that can appeal only to Democrats or Republicans?

JR: Well, no. But I am saying that art conceived of as social and political protest is received less warmly here than it might have been at another time.

JM: That’s because in this country, it is very difficult for us to understand what’s going on in another country, oppressed by dictatorships or devastated by political confusions. It’s very difficult to identify with and really have some feeling for it. It has nothing to do with this time; it’s any time.

JR: And yet if you think of the Sixties and the impact a film like La Chinoise had. . . I remember Columbia students who saw it over and over again in New York at the Kips Bay only a few weeks before they helped to take over the Columbia campus — which happened, in turn, right before the May Events in Paris, which were inspired in part by what happened at Columbia. There was a way in which both news and certain feelings about things were able to travel very quickly.

JM: There was something very similar in the air then in Paris and New York. But if you bring in a film from some South American country today, you won’t get the same response.

JR: I’m both intrigued and a little appalled by the local responses to Tarkovsky’s Stalker, which opened recently at Film Forum. Everyone who deals with the film, including everyone who likes it, says it’s a film about the Soviet Union, and I certainly wouldn’t quarrel with that. But nobody is saying or apparently even conceiving of the possibility that the film could be addressing what’s happening now in America as well, the way that people are living and thinking at this moment. Nobody seems to want to make that connection, which is precisely what makes the film vital and meaningful. People assume it’s “political” because it describes repression and cowardice elsewhere, not because it relates to their own lives. This is what I see as the problem: European work which could actually address the conditions of people’s lives — and here again I include Straub-Huillet — is never being read as such; it’s invariably translated into something else.

JM: Maybe it’s the style and the sensibility of the Tarkovsky film. Godard had a style and sensibility that appealed to certain anarchistic and youthful minds here. He didn’t appeal to the masses — let’s face it. Masses do not know Godard’s name. His form did it. it was his form, his style, his temperament — not the content of his films — that inspired the students of Columbia. But I don’t think Tarkovsky has that kind of electricity that Godard has. No one has; Godard is unique. Tarkovsky’s content is very noble — but it remains only content.

JR: Not for me. The really interesting aspect of Stalker is how much it resembles a structural film — almost any random five minutes has the shape and structure of the whole-while describing the way that we all live and think and lie to ourselves. These two qualities actually support one another — one could even say that they make the film equally unbearable to confront, in a way.

What I’m basically objecting to is critics who write about both film and politics, but who avoid connecting them in any way that might be challenging–such as linking them up with their own lives, for example.

JM: When Amy Taubin writes about a film and interprets it politically, there is nothing sillier.

JR: Even when Peter Biskind or J. Hoberman or Annette Michelson write about film or politics, they often tend to keep each category squeaky-clean, without any serious threat of mutual embrace. My criticism of Millennium Film journal is that it’s not a magazine that wants to change the world; it wants to keep the world exactly the way that it is.

JM: My objection is that it’s not readable! Actually, I have two objections. The main one is, if you haven’t seen the film about which someone in Millennium is writing, there is no way of knowing what it is — there is no perspective, no judgment, no comparison; it’s all descriptive. Equal space and treatment is given to everything there. It’s academic, but not on a high level — like a student’s class assignment.

JR: How would you compare its film coverage to that of October?

JM: October is in a different class. It’s one of the most important magazines that we have, because it brings the best in its own area of interest. You may reject the whole direction, but at least it is a direction.And the pieces are always of a high quality. When it devotes a special issue to Fassbinder after 20 issues, then it’s strayed from that direction — but that’s a real anomaly. And I hope that it won’t happen again, because it destroys what that magazine has achieved.

JR: I couldn’t agree more.

RH: May | ask a question? l wonder what the two of you think about why institutions and artists do things. Very specifically, Emile d’Antonio is someone you probably think is a political filmmaker, and someone who’s even interested in social change. But I don’t think Emile is interested in social change. I think he’s interested in articulating his feelings and ideas about what is happening in society. But i don’t think he’s under any illusion that he’s going to change society.

JR: Well, one criticism that’s been made of a lot of New York work generally — including, say, Yvonne Rainer, as well as Emile d’Antonio — is that it’s about politics without being political. And this differentiates it from some European work. One argument I make about Straub and Huillet is that they really want to change the world. Now you can say that’s utopian, and maybe the only way they might change the world at all is if one person’s consciousness gets changed in a certain direction, then that could lead to other changes. So it’s not a plan for a whole social revolution. But it’s a beginning.

JM: Do you really think that they want to change the world more than Brakhage or [Peter] Kubelka? Do you really believe so?

JR: I don’t know. Maybe they want to change the world in reverse directions.

JM: Certainly Brakhage has affected things politically more through changing the vision of what and how one sees things.

JR: That’s what Straub and Huillet do as well. But what kind of implications do you see in Brakhage’s work and the effect it has on people?

JM: It’s obvious that some believe at this point it’s more important to restructure the government, the social system, and for them that’s the political action. And there are others who feel that’s very superficial, that won’t work unless you change human beings some other ways — and that’s their action, that we have to work on sensibilities and certain feelings and emotions, and that’s a deeper change than just the system. Of course, if you change the system, you try to impose something — l think the Soviets are doing that from the other end. The Poland of politics. Disaster. And the other way, which Brakhage wants and many others, what some religious leaders try — that doesn’t work so easily either.

But these are only two attitudes, and they’re both political actions coming from a very deep engagement in how one sees the world, how one judges where things are weakest and how they should be strengthened. At this point, I support more Brakhage’s direction than those who think of changing the system. From my observation of my short life, I think that Brakhage’s direction at this point is more correct. Therefore, his politics are for me more vital to humanity than those of. . .I don’t want to mention who.

JR: Where my formulation of the problem differs from yours is that I don’t see it as an either/or proposition at all. To me, there’s no way one can change a political structure without changing your own consciousness. Although I do understand that there’s a way in which developing the self in a certain direction can be a movement away from trying to change social and political structures.

JM: I have no doubt that Straub and Brakhage would agree that the most important change is the inner change. From what I heard Straub say at the Collective last spring, I didn’t hear anything which would imply that he’s a political filmmaker in any other, different way. I think he just wants the same thing Brakhage wants.

JR: Let me approach this from a somewhat different angle. It’s often been said that there’s a certain religious atmosphere that’s been created around the American avant-garde, particularly in New York. A friend of mine recently said that going to the Collective or Anthology is a little bit like going to church.

JM: You see the same 100 or 150 people, the same tiny island or group surrounded by 10 million people who are totally disinterested in what’s going on there. So of course you get that impression —

JR: But why is the impression religious rather than political — transcendental rather than materialist? Why does it resemble a sect, and not a cell group?

JM: I don’t see it as religion, I see only the limitation — the small audience, the small interest. When you go to see a commercial film, you know that there will be millions paying money. So you don’t have to feel anything about it; you go home and forget. But here you sit there and know that only 50 or 60 people came to this film, so you feel a little bit friendly, almost, to all the other people who are there. It’s not so much religion; you feel like it’s a community. But that’s natural. There is a certain beauty in it.

JR: It is natural. But I can remember, when l was in college in the mid-Sixties, I was a bit belated in getting interested in avant-garde film. And I can recall a certain attitude I encountered when I did go to see certain things in New York — that if one was serious, one went to everything, or most things; but if one was not serious, one only went to an isolated film here and there. The attitude was a bit like: Why weren’t you in church last Sunday, the way you were supposed to be?

JM: Only Ken Jacobs would say that. He said, “I never notice those who go to my films. I only notice those who don’t come to see my films.” And that is a religious attitude.

JR: It’s understandable, in a way, because you and P. Adams Sitney and Ken Kelman were all going out on limbs — making a commitment which wasn’t just a commitment of careers, but a social and aesthetic commitment. And there was a way of relating to that in a dilettantish manner, and a way of relating to it much more existentially. To me, that’s what created an aura, which was not necessarily willed at all, that made it like a religion.

JM: Maybe it’s impossible in 1982 because of the number of films and videotapes being made today. That’s one of the reasons why I quit Soho News — a situation that was already coming while I was writing for The Village Voice. One of the reasons was that I wanted to do some work of my own, editing my own films. And i could still work on my films and see all of what was being done around me until some point in the Seventies. But it became more and more impossible as the Seventies progressed to see everything and do my own work. Before, one could spend two or three evenings a week and see everything, and still do one’s work.

JR: How does being a filmmaker rather than a critic affect the way you look at films now?

JM: l don’t think that I look at films differently. The difference is only that filmmakers aren’t calling me that often to see their films. And I feel freer when I go to see their films, because I know I don’t have to write about them.

JR: A big problem l’m having right now is with those packages of films by several different filmmakers at the Collective’s retrospective. I nearly always find them indigestible–there are too many gear changes l have to make between each film. For the purposes of a survey on recent avant-garde film, you’d think these programs would be very helpful, but there’s a phenomenological problem. I recently went to a whole program because I was especially interested in seeing a Wyborny film at the end; but by the time I got to it, I didn’t feel that I was able to watch it.

JM: I don’t believe in potpourri programs. I am for one filmmaker in a program, so I’d never do what they’re doing.

JR: Have you ever found that there’s any way to make it work?

JM: It works with some of the classics which we have seen many, many times, but not with new and unfamiliar works. Ballet mécanique wouldn’t fall apart with Étoile de mer, because we know them so well.

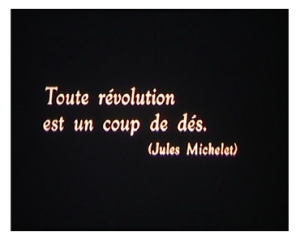

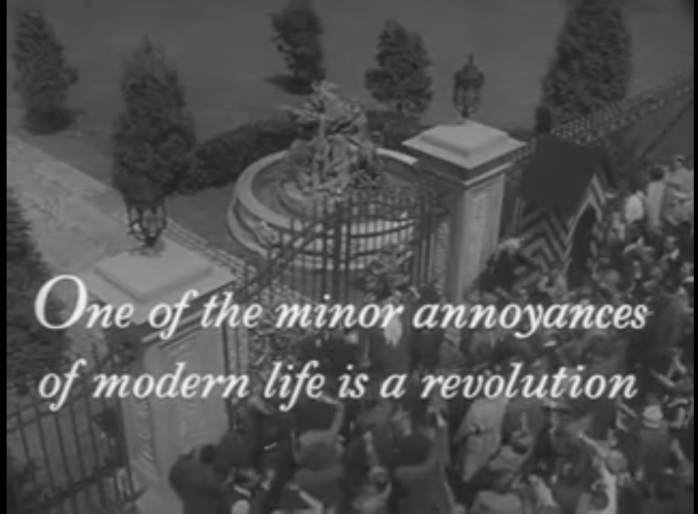

JR: Sometimes, though, certain odd pairings can work surprisingly well. Last night, for instance, at the Straub-Huillet season, Othon and Every Revolution Is a Throw of the Dice and Chaplin’s A King in New York were shown in swift succession, and there were all sorts of beautiful and unexpected continuities — such as the fact that Chaplin begins his film with a revolution. Unfortunately, it’s precisely this aspect of the series that was masked out in the service listings of The New Yorker and The Village Voice, both of which pretend it’s only a straight Straub-Huillet retrospective because their formats apparently can’t even contemplate anything that’s slightly out of the ordinary. It’s here again that the crushing inertia of institutions becomes relevant.

JM: In 1961, we wrote this manifesto of the New American Cinema. Eugene Archer was working for The New York Times then, and I showed it to him and asked him if they could print it. He said, “No, we couldn’t — maybe The Village Voice could run it.” Then I understood, of course, that the only kind of manifesto that The New York Times would print would be a press release, not a manifesto at all. In the same way, for an idea to get into The Village Voice today, it has to become not an idea, but something else.

RH (to IR): I think your notion that institutions are shelters and places of safety and protection is totally false. I don’t think institutions do that; I think they try to fill voids and do what nobody else is doing.

JM: At some point Anthology came in to fill a demand and void, but it’s conceivable that after it fulfills that function, then it becomes something else. This is new in my thinking. But I look back at certain people who were writing about experimental /avant-garde films like Parker Tyler and Amos Vogel, who wasn’t writing but was running the distribution and exhibition side. And the interest and passion of these people, on a very high level, lasted for about a decade, approximately. And then they more or less lost touch and lost interest. For years I would make snide remarks about that, because I thought I can bridge at least two or three generations. But on the other hand, I think now I was wrong to say that, because I think we should not ask from a critic, exhibitor, or disseminator to do anything for any other generation but his or her own.

There’s a certain period when one really gets involved for 10 or 15 years. And if that is really done deeply, so much energy goes into it that later it takes another decade or two just to consummate it. The same applies to institutions. If Anthology Film Archives will serve any other generation of independent filmmakers but that of the Thirties to 1948, or even to 1968 or 1970, that would be perfect. It’s a limited collection, it’s there, you know what it is, it’s no change, it’s perfect. There is so much just to serve that period, to protect those works in the collection we know now what it involves, to collect all the reference materials, etc., so you can really serve in depth university scholars on those 20 or 30 filmmakers. That’s a big job, and it would be terrific just to do that and nothing else. But we’ve expanded, and l don’t really know myself how wise it is to continue to expand and do more than that — to add new works, be in touch, make a video collection. Either it’s a closed museum that represents a certain period or it’s open. When it’s closed, you can’t accuse it of just protecting its own interests, because it has a definite, real function. But if it’s open, then there are different requirements, and one has a right to ask and demand it to really do the job of an open museum—to represent contemporary work that’s being done right now. So I see what you are saying.

So we’re living in an era that’s‚ blasé and pathetic, where people aren’t even worried (laughs) — and they should worry! One day they elect Reagan without thinking, and the next, a couple of years later, again without thinking, they begin to turn against him.