From Film: The Front Line 1983 (Denver, CO: Arden Press, 1983). Due to the length of this, I’ll be posting it in four installments. — J.R.

Tenants of the house,

Thoughts of a dry brain in a dry season.

T.S. Eliot, Gerontion

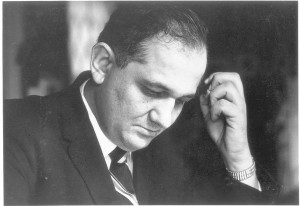

Preface: When I was approached last year about inaugurating a series of volumes surveying recent avant-garde film, I immediately started to wonder about how this could be done. Having lived nearly eight years in Paris and London and about as long in New York, I’ve had several opportunities to note the relative degree of information flow between these and other centers of avant-garde film activity, and the growing isolation of New York from these other centers made my own fixed vantage point less than ideal in some ways. When a colleague told me that Jonas Mekas had recently said that it was no longer possible to know what was happening in experimental film as a whole, a bell of recognition rang in my head, and I knew at once that Mekas was the only available oracle l could turn to. The Lithuanian patron saint of the American avant-garde film, now 60, has been an American filmmaker for at least half of his life, and a chronicler of the avant-garde film in New York — mainly in The Village Voice and (more briefly) Soho News — for at least 15 years. If he no longer knew with confidence where we were, a consideration of the nature of the very problem of our ignorance was clearly in order.

Out of this need and curiosity, the two following conversations took shape, with Mekas’s kind consent, at the temporary headquarters of Anthology Film Archives on Broadway in lower Manhattan, in late July and early November 1982. Robert Haller, executive director of Anthology, was present at both discussions, and some of his remarks are also included.

The second dialogue, longer and somewhat more polemical than the first, occurred during a two-week season at the Public Theater devoted to Jean-Marie Straub and Daniele Huillet and filmmakers they admire (about two dozen films in all) that l was involved in curating at the time, and which became a logical reference point for part of our discussion. The results have been edited by Mekas as well as myself.

— J.R.

JM: One of the reasons, maybe, for the new situation is that for the last five or seven years, the political avant-garde‚–at least the avant-garde that calls itself political — has dominated: the Screen group, Jump Cut, Cineaste, Camera Obscura. To tell you the truth, the way i really feel about these films, they are neither political nor avant-garde. Only the talking and writing about these films, in Screen, Jump Cut, etc., has a political tint or style. It’s not politics — it’s, rather, politics as a fashion, or style. It has nothing to do with changing the status quo of society.

Nobody writes about Klaus Wyborny in those places, although Wyborny is more interesting and more political. Chris Welsby is mentioned, but he’s not given the credit he deserves because all these politically minded writers like Peter Wollen are wallowing in certain semi-political and semi-feminist ideas. And semiotics is part of it. Fashionable politics. They can really make a film sound very interesting. They are all writers. They say, “A man is crossing the street”–and you think, “That sounds very interesting,” but you look at the film and it’s got nothing, it’s just a man crossing a street — you could get a child to do it. There is no more qualitative, historical, comparative criticism. From the standpoint of semiotics and structuralism, you can analyze any image; any and every image is illuminating. You can talk about any frame for hours: it has nothing to do with cinema and nothing to do with anything. But it has to do with semiotics and analyzing of lines and shapes and light and how they all relate to history and masculine and feminine. We had a lot of that kind of writing here. Daryl Chin’s writing, for instance, started out as perceptive and sensitive. But no matter what he sees, he can write three or four or five single-spaced pages about it, and if one asks, “Should I go to see this film?‚” one gets only a description. You wind up knowing nothing. Everyone gets a lot of space, and that’s it.

JR: One problem is, when critics do tell you what films to go to, they generally aren’t writing about the avant-garde. Whereas people who do write about avant-garde often argue that there’s something outdated about assigning grades to works. What bothers me even more is that critics in this country who are widely thought to be intellectuals of some sort — I’m thinking of people like Kael, Sarris, Simon, and Kauffmann—don’t deal with intellectual films or subjects at all, as a rule.

JM: Yes, but I cannot reproach them for not treating avant-garde films anymore than I can reproach certain musicians for preferring certain instruments, or certain painters for preferring certain subjects or techniques. I mean, they are very deep in their own areas and doing well, and I think we have that in independent cinema as well, and in art criticism. There are no universal minds who can cover all the periods and styles. I think Andrew [Sarris] is doing very well in illuminating a certain type of film, and that’s it.

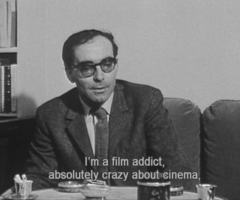

JR: Sure. But in the public mind, he and the others are perceived somehow as writing about and representing the whole of cinema. That isn’t entirely their fault, of course–but it does lead to an enormous amount of omission and even repression. Five years ago, in London, Andrew was insisting to me that nobody but nobody was interested in Godard anymore — but, of course, his idea of “somebody” now excludes the avant-garde. It’s a vicious circle that becomes all the more exclusive when avant-garde critics ignore many of Godard’s works as well.

JM; l don’t think Sarris was so wrong about that. The avant-garde, especially the American avant-garde, was never really interested in Godard. There was nothing in Godard for the American avant-garde, politically or formally. The only thing about Andrew is that he should just keep his mouth shut when it comes to avant-garde films in general. But he feels some time he has to open his mouth and say‚ “Maya Deren stinks‚” or “Stan Brakhage stinks”. By the same token, I wouldn’t presume to pass judgment on Hollywood films anymore.

JR: But you used to, and I found it very interesting when you did.

JM: Well, I saw absolutely every film that opened until maybe 1970. Now my work doesn’t permit me to catch up with everything, so I feel I have no right to speak about it. I cannot compare.

JR: This may be because of all my years in Europe, but it seems to me that a lot of my European friends tend to see all kinds of films, and see them in relation to each other.

JM: I don’t know who your friends are, but some of them are publishing film magazines, and if you look at the magazines like Cahiers du Cinéma or Chaplin, none of them write about the avant-garde except for Cahiers, once in a blue moon. You need to have a blockbuster like Michael Snow or Nam June Paik in order to get attention. These magazines are not balanced.

JR: What about the Monthly Film Bulletin in England?

JM: l’ll have to look at that one. For the others, I don’t think those writers or magazines see all films. They do not see the avant-garde. I have been there with shows of American avant-garde, and they never came to see the films.

ROBERT HALLER: Lucy Fischer is someone who writes about both commercial and avant-garde film.

JR: Sure, and there are others. i find, as a freelancer, that the most interesting films nowadays are quite often the ones that I can’t write about, because they’re not available or prominent enough. This is part of what I meant earlier about service- and consumer-oriented criticism.

JM: Dreyer’s Gertrud has no distributor in the U.S.!

RH: There’s been a collapse of the 16mm distributors in this country. Films, Inc. have bought out virtually everybody. It’s a giant, and there are a couple of pygmies, and that’s it.

JR: What makes me angry is that people keep saying that everything will become available on cassette soon — all of Brakhage, for example. It’s not true.

JM: At the Film-makers’ Cooperative in 1962 or ’63 we discussed that — almost 20 years ago. Now it seems like it’s already here. I don’t know if it’s really here. All | see is past enthusiasms and hopes. We get all these schedules from across the country of what gets shown — and there are certain constants, like Brakhage and Snow and local people. What understanding there is about what’s shown, I don’t know. Some aspects are rather bothersome. They rent only certain works–you begin to see the same titles over and over. Take Ernie Gehr. You will see Serene Velocity again and again, while a major film like Still rents once every two years. And others aren’t seen at all.

JR: Is this because of what’s written?

JM: lt’s partly that. Another thing is they feel they can’t devote more to Ernie Cehr than one program every two years or so, so they tend to choose what’s shown the most often. It is a problem.

RH: The situation isn’t the same as it was 20 years ago, in those places where museums and universities had bought collections and show their films on a regular basis. Apart from that, it is like it was 20 years ago.

JM: We were talking about places like New York, Chicago, and San Francisco, where people who were interested in the avant-garde film saw all of it, whatever was shown, so they had a wider understanding or knowledge. Now, if you are in Kansas and the regional art center will have, let’s say, 20 film programs a year, maybe 16 of these will be devoted to Hollywood and European art films. And of the remaining four, two will be local works and maybe one or two will be classic avant-garde films. . . .I don’t know how much knowledge there is now. I know that we show Sidney Peterson’s films every four months at Anthology, and we always have three or four people.

(to be continued)