[2017 Preface: I’m reposting this article less than a month after its last posting on this site because Powerhouse Films in the U.K. has just sent me, at my request, its impressive “Limited Dual Format Edition” of this remarkable movie, and so far, the only complaint I have relevant to its riches is that they didn’t access this 1978 article about it any sooner. If they had, some of the uncertainties and/or wrong guesses made by Glenn Kenny and Nick Pinkerton in their often informative audiocommentary probably wouldn’t be there. For the record then–to cite only a couple of matters not covered in the article below that conflict with their suppositions (apart from the mispronounciation of La Jolla)–in 1953, at age ten, I already knew who Dr. Seuss was because many of his books were already widely available but, even as a devoted radio listener, I didn’t know who Peter Lind Hayes and Mary Healy were.]

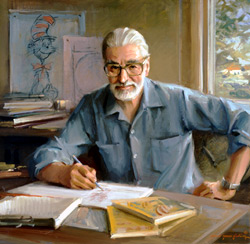

The principal source of this article — written for American Film, and published in their October 1978 issue — was a fairly lengthy phone conversation I once had with Theodor Seuss Geisel (1904-1991), better known as Dr. Seuss, when I was living in San Diego. More specifically, this happened while I was teaching in the Visual Arts Department at the University of California, San Diego, and booked The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T. for one of my film classes. I can no longer call whether this was for my course called Paranoia or for one of Raymond Durgnat’s classes that I took over for him after he unexpectedly and rather mysteriously returned to London in the middle of a quarter. (He was also a big fan of the film.)

Geisel, the main auteur of the film (at least as I saw it), also lived in San Diego, and hoping that he could come to the class as a guest lecturer, I managed to get ahold of his address and wrote him a letter. By way of replying with a friendly refusal, Geisel called me one day at the house in a Del Mar canyon that I was subletting at the time (along with filmmaker Louis Hock and, for the time he was around, Ray Durgnat) and politely begged off, explaining that his relation to this movie was rather traumatic. To explain himself, he gave me a lengthy account of his friendship in the U.S. Army with Carl Foreman and Stanley Kramer, their joint project to make a fantasy film, and various disastrous occurrences that interfered with the original plans. I also recall asking him if I could write about this and he said sure, as long as I didn’t quote him — which is why I refrained from mentioning our phone conversation in the article. (Another thing I refrained from mentioning, at his request, was the fact that Kramer wound up directing a good deal of the film after Roy Rowland suffered some sort of breakdown during the film’s production.)

American Film was a rather bland mainstream monthly whose fees were largely supporting me and paying my rent while I was writing my first published (and, to date, least mainstream) book, Moving Places: A Life at the Movies (1980). I’ve recently tweaked the editing of this piece in a few spots—J.R.

Take Two: The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T.

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Neglected films come in various shapes and sizes. There are movies whose aesthetic importance is overlooked or whose social impact has been forgotten simply because prints are scarce or unavailable. There are movies nurtured by nostalgia, touchstones or tombstones of former feelings, that are more prone to reappear, like phantoms on television.

Then there is a third category: the unclassifiable oddity. Without a comfortable pigeonhole to encapsulate its essential qualities — a familiar genre, star, or auteur — it is doomed to walk the night as an isolated freak, excluded from most textbooks and popular histories because it doesn’t “fit” any ordinary survey standards.

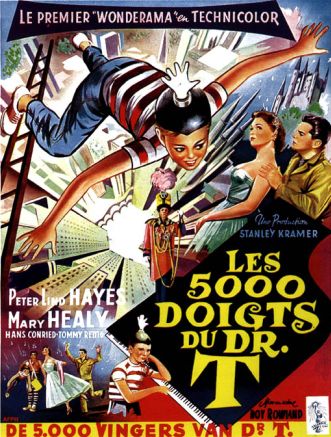

The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T. is one such outcast, although for me it also has distinctly nostalgic overtones. I first saw it when I was ten years old, on a family trip to New York in June 1953, shortly after it opened. I liked it so much that I returned to it twice when it eventually reached my hometown in Alabama later in the year.

Bart Collins (Tommy Rettig), the movie’s hero, was also ten, which obviously helped to bolster my attachment to this weird musical fantasy. But that wasn’t the whole story. I could sense that this movie postulated — and was postulated on — a certain form of rebellion against the adult world. Aside from short episodes at the beginning and the end, the film is offered as Bart’s nightmare, a pure distillation of a ten-year-old boy’s grasp of his world and his sense of the degree to which adults occupy and control it.

The film was written by Alan Scott and Dr. Seuss. The latter’s name, of course, was no less familiar to us. I knew that his real name was Theodor Seuss Geisel. I had checked out from the library several of his illustrated children’s books, including The Cat in the Hat and Horton Hatches the Egg. I also knew that he’d created the title character of Gerald McBoing, Boing, the cartoon that had won an Academy Award for 1950.

What I hadn’t realized then was that Geisel had already been associated with two previous Oscar winners. While he was attached to Frank Capra’s filmmaking unit during World War II, he wrote an indoctrination film, Your Job in Germany, which was later released by Warner Bros. under the title Hitler Lives, and won the 1945 Academy Award as the best documentary short. The following year, as a civilian, in collaboration with his wife, Helen Marion Palmer, he wrote Design for Death — described in the press as “a history of the Japanese people” — which was released by RKO and won the Academy Award for best documentary feature.

It was during the war that Giesel, Kramer, and Carl Foreman, all serving together in Capra’s film unit, first hit on the idea of some day concocting a lavish film fantasy. After the war, Kramer went on to become a producer, and Foreman worked with him as scriptwriter on Home of the Brave, Champion, The Men, and Cyrano de Bergerac.

But during the production of High Noon, Foreman was summoned to testify before the House Committee on Un-American Activities. Unlike Kramer, he refused to cooperate and immediately was blacklisted. Foreman severed his association with Kramer and moved to England, and the director’s post on Kramer and Geisel’s project — now an expensive production to be distributed by Columbia Pictures — went to Roy Rowland, a former assistant to W.S. Van Dyke on Tarzan films.

Geisel’s idea for the film stemmed from piano lessons he’d had as a boy “from a man who rapped my knuckles with a pencil whenever I made a mistake….I made up my mind I would get even with that man. It took me 43 years to catch up with him.” Thus was born the ferocious Dr. Terwilliker (Hans Conreid), Bart’s authoritarian piano teacher whose institute serves as the sole location of Bart’s feature-length dream.

Certain changes in Geisel’s conception were made for commercial reasons. In the “real-life” episodes, Bart befriends a plumber named Zabladowski working in his house who turns up later in Bart’s dream, where he functions as an alternate father figure. Geisel wrote the part for Karl Malden, but it was decided, instead, to use Peter Lind Hayes, a popular radio star who formed a singing team with Mary Healy. Healy herself was given the role of Bart’s mother. This led to an injection of “romantic” interest between Bart’s mother and Zabladowski.

Various difficulties beset the shooting. Probably the most spectacular of these involved the climactic title sequence, when Dr. T. marshals 500 boys to play his own composition, “Ten Happy Fingers,” on two gigantic keyboards — a notion of Busby Berkeley at his wildest. The scene required the film’s most spacious set, designed by Rudolph Sternad and built on RKO’s largest sound stage.

The problems started when three days of rain began to flood the set. Only about 400 boys were eventually used in this sequence. Between takes, all of them gorged themselves on hot dogs in the studio commissary. One boy became ill on the set and threw up — setting off a violent chain reaction. The resulting surrealism must have been more unsettling than anything Salvador Dali might have imagined.

As a paranoid fantasy, the film is quite straightforward. Falling asleep after a piano lesson with Dr. T., Bart finds himself in the dream institute as the first recruit for the 5000-fingered recital, forced to wear an official Terwilliker beanie. Soon the boy is in flight from legions of guards, the most bizarre of which are Judson and Whitney (John and Robert Heasley), Siamese twins connected by a single gray beard who pursue Bart on roller skates [see below]. After attempting to enlist the aid of a reluctant Zabladowski — who is installing sinks to prepare for the influx of 499 other boys — Bart discovers that Dr. T. has issued an order to have the plumber disintegrated at dawn.

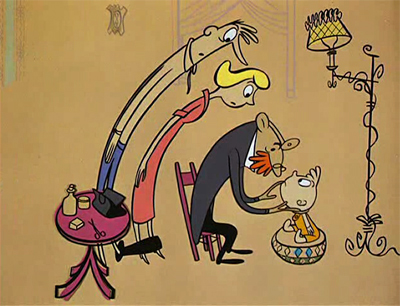

Continuing his flight, Bart comes across a dungeon in which are kept all the musicians who play instruments other than the piano. The real Dr. T. had described them as “scratchy violins, screechy piccolos, nauseating trumpets, et cetera, et cetera.” This occasions the film’s most remarkable sequence — a ballet choreographed by Eugene Loring and featuring an assembly of green-skinned prisoners performing on outlandish instruments.

One xylophone is a radiator, and another is played by several men with brightly colored, crisscrossing mittens. Dress dummies serve as bass fiddles, and violinists and tuba players carry wraparound instruments encasing their entire bodies. Other parts of the orchestra suggest torture instruments (an enormous harp strummed by prisoners’ heads), surreal objects (a man dancing on a drum with abnormally long mallets) and circus props (a man on a high wire sailing across the set to strike a small cymbal).

Bart carries the execution order to Zabladownski and engages him in a blood pact, joining together their pricked thumbs and getting him to assent to the Boy Scouts’ pledge. But Terwilliker’s guards turn up, and Bart and Zabladowski are imprisoned in a dungeon. There they concoct a magic potion designed tp sabotage the grand recital by swallowing up noise, through Zabladowski warns that it may be “atomic”.

The formula works, and the 500 little boys, led by Bart, celebrate their palace revolution and defeat of Dr. T by pounding out a discordant version of “Chopsticks” with their hands and feet. (The only exception — an indelible passing detail — is a tearful boy who still wants to play “Ten Happy Fingers”.) The portion proves to be atomic after all, sending up smoke, crackling sparks, and finally explosions.

Bart awakes in terror beside his piano, and in a hasty conclusion, it is implied that maybe the preceding wasn’t only a dream. He and Zabladowski still have bandages on their thumbs from their blood pact. The movie ends with Bart playing outside with a baseball and mitt, accompanied by his dog, an image of Middle American normality that evokes Norman Rockwell.

***

Why was the film such a resounding flop at the box office, reportedly losing more than a million dollars? Acknowledging certain lapses — mainly a few descents into tacky sentimentality or awkward pictorial whimsy — I would still guess that its commercial failure stemmed from its strangeness and originality, which gave audiences more than they could handle.

Like the contents of Bart’s pockets that go into the “Music-Fix” magic potion — an endless assortment of objets that is beautifully “rhymed” with the confiscated possessions of the 499 other boys — the movie remains a rather awesome hodgepodge. The steps of different shapes and sizes leading up to Dr. T.’s headquarters, and the Flash Gordon-like paraphernalia found inside, suggest the “mental projections” of German expressionist films from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari to Metropolis. But the tunes of Frederick Höllander (alternately chipper and saccherine) and the extravagant uses of 50s Technicolor interact with this tradition in a decidedly peculiar way, as if Dr. Mabuse and Esther Williams were suddenly to find themselves in the same movie.

Seen today, the film has an additional layer of interest as a complex reflection of American attitudes and feelings during that period. For one thing, the popular applications of Freud are everywhere apparent, as in the dreamlike equation made by Bart after his blood pact with Zabladowski. He accepts the plumber as a father figure and, consequently, as a husband for his widowed mother (in striking contrast to Dr. T., who holds his mother under a sinister hypnotic trance).

If we pick up some clues from the sociological approach of Raymond Durgnat — one of the few critics to have acknowledged the film’s special interest — the kinship of this oddity with other movies of period becomes much more apparent. Far from being a “pure’ fantasy, its nightmarish landscapes and details evoke Cold War anxieties linked in the public’s mind with Russia, Korea, and the atomic bomb, as well as memories of World War II. Such diverse details as the electrified barbed wire and searchlights surrounding the Terwilliker institute and the grotesque goose steps performed by Dr. T. — after being dressed in his elaborate “Do-Mi-Do Duds” for the recital — hark back to related fears.

The anti-egghead bias of the early 50s is clearly bound up with in the portrayal of Dr. T. As embodied in Hans Conreid’s brilliant performance, the character is a veritable anthology of negative responses to Europeanized and “feminized” notions of high culture. From his pink powder-puff slippers and his vaguely continental accent to his stern disciplinary manner, he makes a striking contrast to the “manly” working-class virtues of an all-American Zabladowski.

None of this is meant to suggest that the film can’t — or shouldn’t — be enjoyed by children and adults today. On the contrary, when it was revived at a children’s show at Filmex in Los Angeles last spring, the response was overwhelmingly warm and enthusiastic. I’m sure that many of the 10-year-old boys must have identified with Bart as strongly as I did 25 years ago. And the movie’s cockeyed inventions still shine with a singularity that places this film in a class by itself.

—American Film, October 1978