R.I.P. Nicolas Roeg, 1928-2018. From The Movie no. 85, 1981.— J.R.

It is surely more than just a coincidence that director Nicolas Roeg has used leading pop stars and rock personalities in three of his five features to date. The sheer satanic presences of Mick Jagger in Performance (1970), of David Bowie in The Man Who Fell To Earth (1976) and, to a lesser extent, Art Garfunkel in Bad Timing (1980), all have something slightly magical about them — as if they held the implicit promise that unusual and outsized events were going to take place around and, in large measure, because of them. Boldly delineated in each case like the demonic princes of dark impulses, they are offered as guides and portals into the decadent fantasies which these films often traffic in. As Roeg told critic Harlan Kennedy in an interview:

What I find interesting about singers is that they all have the qualities of performers but they’re untouched in terms of acting. They’re not from the New York school of this or that: they’re not from the London theatre….So many actors have lost their intent, their beginnings. They’re not this travelling group of players that one evening is a king, another evening is a beggar. What I love about the other actors — the non-actors, the singers — is that they don’t know who they are yet. And actors shouldn’t know.

Born in London in 1928, Roeg entered cinema as a clapper-boy at the age of 19, gradually working his way up to cinematography before he got around to directing. Starting off with an assortment of jobs, including assistant camera-operator on Bhowani Junction (1956), camera-operator on The Trials of Oscar Wilde (1960), work on several scripts (including the original story for A Prize of Arms, a 1962 thriller) and second-unit cameraman on Lawrence of Arabia (1962 ) and Judith (1965), he served as director of photography on a number of distinguished films. Apart from working with Roger Corman (The Masque of the Red Death, 1964), François Truffaut (Fahrenheit 451, 1966), and John Schlesinger (Far From the Madding Crowd, 1967 ), he shot two films apiece for Clive Donner (The Caretaker, 1963; Nothing But the Best, 1964) and Richard Lester (A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, 1966; Petulia, 1968).

It was on Petulia –– shot in San Francisco, the mecca of the counter-culture. nearthe peak of the media’s interest in hippies — that Roeg can be said to have arrived at many of the rudiments of style and structure that characterize his own, subsequent films, the first of which was Performance. An essential part of this manner is a form of rapid and fragmented, kaleidoscopic cross-cutting between diverse strands in a narrative tapestry, an approach that creates meaning largely through unexpected juxtapositions. By and large, it is a wide-ranging, impressionistic method which can make a relatively simple plot multilayered and complex, and an already difficult plot a series of puzzles and mazes.

This was clearly the case with Performance, which Roeg co-directed with Donald Cammell. While it was Cammell who initiated the project and wrote the original script, Roeg’s contributions, both as co-director and cinematographer, were such that one could speak of a certain symbiosis which paralleled the close merging of two personalities, Chas Devlin (James Fox) and Turner (Mick Jagger), in the film’s doppelgänger plot.

Like all subsequent Roeg movies — barring only Bad Timing,whose own subtitle, A Sensual Obsession, could work just as well for any of the others — Performance essentially revolves around the dramatic confrontation caused by one or more characters fleeing from a native culture associated with death into an alien environment that profoundly challenges their former identities, This could be read as the central religious myth for the youth of the Seventies. who tried drugs and sexual politics of various persuasions as the means to share an alien experience. And the metaphor for escape and change can be a retired rock singer’s pad, the Australian outback, the Gothic structures of Venice, or, quite simply. the planet Earth.

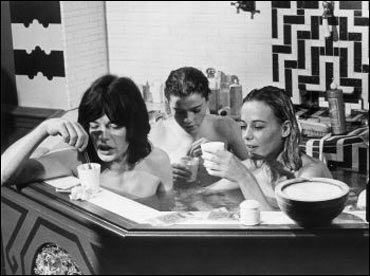

In the case of Performance, Chas Devlin, a sadistic, small-time gangster on the run from his former boss Harry Flowers after committing a murder, finds himself taking refuge in the home of an ex-pop star. Turner, who lives with two bisexual women (played by Anita Pallenberg and Michèle Breton). With the assistance of a rather esoteric drug known as amanita muscaria, Chas goes through what one might refer to as an identity transplant with Turner, so that, as in Bergman’s Persona (1966), a mysterious change of roles and personalities takes place.

Walkabout (1971), Roeg’s first solo effort as a director, displays a comparable shift of power between characters and cultures, although the circumstances are quite different. Here an English adolescent girl (Jenny Agutter) and her younger brother (Lucien John, Roeg’s own son) are in flight from white civilization across the Australian outback after their father has inexplicably tried to kill them before shooting himself. Eventually they meet an Aborigine youth (David Gulpilil) on his walkabout — a rite to establish his manhood in isolation from his tribe — who leads the white children back to final stretch and commits suicide as mysteriously as their father on the edge of the bush country.

***

Ironically, white culture remains present throughout much of the film, thanks to the heroine’s portable radio, incongruously spewing out pop music from Sydney in the middle of nowhere. By the same token, the innocent sensual pleasures of the bush — such as the memorable lyrical and romantic sequence of Jenny Agutter swimming nude in a mountain pool — permanently mark the consciousness of the teenage girl in her ‘civilized’ life to come. Beautifully shot (again. by Roeg himself) on location, Walkabout may well be the least metaphysical and most concretely poetic of Roeg’s features — using the exotic animal,. insect, and plant life of the outback in a manner that gracefully makes documentary and fantasy seem like inextricable parts of the same natural narrative process.

In Don’t Look Now (1973), one of his biggest commercial successes, Roeg adapted an occult short story by Daphne du Maurier with Allan Scott and Chris Bryant, and deliberately set out to do something rather different from his previous films. This time he assigned the camerawork to Anthony’Richmond (who also shot his next two features) and was striving, as he put it to interviewers, “to make a yarn, a film that would keep going as a yarn.”

Wishing to maintain his privacy and anonymity, and dealing with Farnsworth chiefly by phone, Newton later builds a private space program — ultimately designed, it transpires, to return him to his wife and children, who are suffering from a lack of water on their distant planet. But before he can put this plan into effect, he is kidnapped by a crime syndicate which also kills Farnsworth, and subjected to punishing tests to determine his identity, destroying his clairvoyant powers. Years later, Dr. Nathan Bryce (Rip Torn), once a consultant to Newton who now lives with the latter’s former mistress Mary Lou (Candy Clark), tracks the alien down through a record album made incognito — a striking point at which the roles of the real-life Bowie and the character fuse — and finds him an alcoholic cripple who shows no sign of aging.

As a mythical deity who often gazes at several TV images at once to relax, David Bowie’s persona as Newton recalls some of the other-worldly nature of Mick Jagger as Turner presiding over his sound equipment. However, the figure of Dr. Alex Linden (played by Art Garfunkel), an American psychiatrist living in Vienna in Bad Timing, conjures up a somewhat more troubled, less heroic image. But Bad Timing differs in other respects from its predecessors, partly by focusing more on a doomed relationship than on a doomed individual. Starting this time with an original script by Yale Udoff, Roeg explores the increasing obsessiveness of both Linden in his jealous involvement with Milena Flaherty (Theresa Russell), a promiscuous fellow American, and inspector Netusil (Harvey Keitel), an Austrian investigator seeking to work out the role played by Linden in Milena’s suicide attempt.

While these two obsessions are consecutive in terms of plot, Roeg’s scattershot method of cross-cutting allows him to explore both strands at once, as parts of the same space-time continuum –- and even to compare and contrast Linden and Netusil in yet another form of Roegian doubling. “What is detection if not confession?” Netusil asks rhetorically at one point. It is a succinct version of the kinky puzzle as a form of personal expression, populated by Roeg’s gallery of irregulars, and one that characterizes all five of his intricate, hallucinated and haunting features.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM