This appeared in the August 26, 1994 issue of the Chicago Reader. —J.R.

*** DIVERTIMENTO

(A must-see)

Directed by Jacques Rivette

Written by Pascal Bonitzer, Christine Laurent, and Rivette

With Michel Piccoli, Jane Birkin, Emmanuelle Béart, David Bursztein, Gilles Arbona, Marianne Denicourt, and the hand of Bernard Dufour.

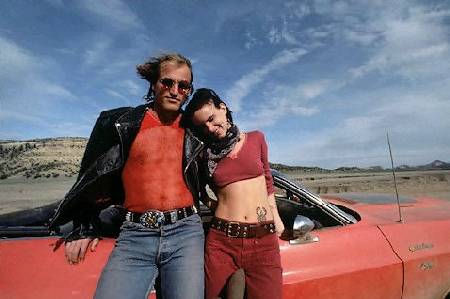

NATURAL BORN KILLERS

(No stars–Worthless)

Directed by Oliver Stone

Written by David Veloz, Richard Rutowski, Stone, and Quentin Tarantino

With Woody Harrelson, Juliette Lewis, Robert Downey Jr., Tommy Lee Jones, Tom Sizemore, Rodney Dangerfield, Edie McClurg, Sean Stone, and Russell Means.

One of the more deceitful explanations for the compulsive repetition that informs most contemporary movies is that Hollywood is simply giving the public what they want. The idea that they even know what they want is pretty dubious to begin with — especially if one factors out all the publicity and hype that supposedly speaks for them. And the argument that moviemakers have any better sense of what the public wants is usually self-serving propaganda.

A more likely explanation for all the recycling is that it serves business interests — and contrary to what you read in Variety and Premiere, that is not necessarily the same thing as serving the public. “They liked it before, so I guess they’ll like it again” is an argument that implies first that people always like what they’ve spent their money on, and second that they want their pleasures endlessly repeated rather than varied. Hollywood would prefer moviemaking to be an exact science, not an unpredictable art, and if the repetition leads to a certain amount of boredom for those of us in the theaters, it does enable the producers and accountants to sleep better — at least in theory. (Sometimes this process backfires, as in The Last Action Hero.)

In their very different ways, two movies opening this week — Jacques Rivette’s Divertimento and Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers — owe their very existence to this kind of automatic-pilot thinking. The first of these, a mainstream effort by an avant-garde filmmaker, fulfills a contractual agreement Rivette made to edit a shorter, presumably more commercial version of the 1991 La belle noiseuse, which was a better film but twice as long. Stone’s movie, an avant-garde effort by a mainstream filmmaker, basically repeats and expands some of the “experimental” stylistic procedures of his JFK but using very different material. This material, recycled from many other movies (mainly outlaw-lovers-on-the-run thrillers like Gun Crazy, Bonnie and Clyde, and Wild at Heart), addresses a familiar theme, the media’s preoccupation with violence. Yet Natural Born Killers is clearly intended to yield something new, provocative, and exciting.

Divertimento represents the fourth time in Rivette’s career that he’s carved two films out of the same basic material, and the third time this process has yielded a shorter, inferior, compromised version. In the 60s the producer of Rivette’s first lengthy feature, the 252-minute L’amour fou, demanded a version half as long — the version that premiered in Paris, which Rivette disowned. It’s not been made clear whether Rivette himself edited this version (which I’ve never seen), but it quickly dropped from sight after the four-hour version opened a little later and did substantially better at the box office.

In 1970 Rivette shot 30 hours of footage for Out 1, and the following year edited them down into a 760-minute serial intended for — but rejected by — French TV; Rivette then spent the better part of a year editing the nearly 13-hour serial into a very different 255-minute feature, Out 1: Spectre. This is the only time he has ever managed to create two works of equivalent stature out of the same material — works that can even be said to complement and enhance each other, because the same shots sometimes have radically different meanings in the two films. (Broadly speaking, the serial is a comedy with tragic undertones, Spectre an anguished mystery with comic undertones; significantly, Rivette worked with different editors on the two versions.)

Rivette’s 1983 two-hour Love on the Ground is a minor work, but at a 1989 Rivette retrospective in Rotterdam I saw a superior three-hour version — the first I knew of its existence. Rivette told me on that occasion that it was the only version he believed in; he implied that the release version merely honored his original contract.

Divertimento seems to have come out of a similar situation: Rivette made an agreement to edit a two-hour version of La belle noiseuse for TV. When La belle noiseuse was screened at Rotterdam in 1991, Rivette requested that the two-hour version not be shown there as well — yet from our point of view, the matter isn’t quite that simple. The two-hour Love on the Ground seems to me a failure, but on its own terms Divertimento is a success — as fluid and accessible as anything Rivette has done. Like Orson Welles’s The Stranger, this is a difficult director’s attempt to prove that he can deliver the goods just like his more bankable colleagues.

Another thing Divertimento has going for it is that, unlike L’amour fou, Out 1, and Love on the Ground, it’s not simply a reediting of a longer film. It was mainly put together from alternate takes — a procedure possible in this case because two versions of La belle noiseuse were conceived at the outset. Thus the performances are somewhat different as well as the overall tone, which is lighter; it begins differently, ends differently, and feels to some degree like another picture, even though the overall story is the same. For those who haven’t seen La belle noiseuse, Divertimento will be simply one of the best French movies to show in Chicago this year. And for those who have, it’s a demonstration of what happens when a relatively dense and weighty work gets stripped down for action — a process mainly involving losses but also entailing a few gains.

Very loosely adapted from Balzac’s novella The Unknown Masterpiece, the plot mainly concerns the intense interactions of two couples over a few days in the south of France, at a lovely village near Montpellier. A young artist (David Bursztein) vacationing there with his lover (Emmanuelle Béart) is taken by his dealer to meet an admired but long-inactive older artist named Frenhofer (Michel Piccoli), who lives in a nearby 18th-century chateau with his former model (Jane Birkin). After the five spend an evening together, Frenhofer decides to make another stab at his unfinished masterpiece, a canvas he calls La belle noiseuse, enlisting the young painter’s girlfriend as his nude model. By the end of the film, all four of these people and their relationships to art and life and to each other have been changed, and the abstract as well as concrete meanings of Frenhofer’s masterpiece have been comparably transformed.

Part of what’s lost in Divertimento is the sense of duration in Frenhofer’s work sessions with his model, which are still depicted but not shown in the same painstaking detail. Also lost are the various rifts, tensions, alliances, and realliances these sessions engender outside the artist’s studio. And because one is no longer living through these experiences with the characters, the characters themselves become more distant, less layered and complex. On the other hand, certain irritations in the longer version — extraneous scenes and dubious details about the ways artists work — are gone. The eleventh-hour appearance of the younger artist’s sister, which seemed to introduce gratuitous complications and diversions in the long version, seems entirely functional here.

Most interesting, Divertimento reveals Rivette’s unexpected strength as a conventional editor, which the uses of duration in all his longer films tend to obscure. Over a decade ago, Jean-Marie Straub made this startling observation: “A lot of people think that Eisenstein is the greatest editor, because he has some theories about it, but this is not true. Chaplin was greater, I think, in editing, only it is not so obvious. Chaplin was more precise than Eisenstein, and the man after Chaplin who is the most precise is surely Rivette.”

What Straub had in mind, I think, is Chaplin’s and Rivette’s ability to edit in relation to content: emotional content, narrative content, performance content. For both directors, editing is a precise answer to the question of what a particular shot’s meaning is — where this meaning begins and where it ends. The fleet beauty of Divertimento largely rests on Rivette’s precise definition of the narrative in La belle noiseuse. Everything that isn’t part of that narrative, which proves to be a great deal, is ruthlessly suppressed, but what remains is a perfect piece of clockwork — right up to Frenhofer’s last mordant line to his art dealer: “Let’s get down to figures.”

The good news about Natural Born Killers is that it’s Stone’s first avant-garde film; unfortunately, that’s the bad news too. The fact that he currently has the power to do just about anything he wants as a moviemaker is certainly worth noting, but the fact that he uses this power to grind out something as truly awful as this delirious, monotonous feature-length music video should provide a cautionary lesson for filmmakers everywhere. If, as many people appear to believe, power is the ultimate value in contemporary Hollywood — it’s not what you do but what you have, and not what you say but what you show (and show off) — Natural Born Killers offers clinching evidence of just how boring the products of such a value can be. Every time I nodded off in this movie, it was with the secure knowledge that whenever I snapped to, I’d be in the same place.

Natural Born Killers treats that current journalistic standby, the media’s exploitation of violence. A cartoonish fictional couple named Mickey and Mallory (Woody Harrelson and Juliette Lewis) meet cute, then go on a mainly gratuitous killing spree to celebrate their passion, beginning with Mallory’s oafish parents and ending with their arrest 50 corpses and three weeks later; they wind up inspiring a prison revolt in the second half of the film. Most of the story is told in terms of the media’s hyped-up glamorizing of their exploits; the central figure here is a frenetic TV personality named Wayne Gale (Robert Downey Jr., speaking in a Robin Leach accent) who has a show called American Maniacs. In fact the movie’s own souped-up docudrama methods are almost impossible to distinguish from Gale’s. (Maybe that’s the point — though if it is, I’d rather watch junk TV and get the same effects with fewer pretensions.) A flashback of Mickey and Mallory’s first meeting, for instance, takes the form of a TV sitcom called I Love Mallory, full of four-letter words, bleeps covering other or the same four-letter words, greasy undershirts, and crude intimations of incest from Rodney Dangerfield as Mallory’s father. A telling aspect of Stone’s “daring” critique of the media is that the sensation mongering is presided over most noticeably by non-Americans — a hypocritical Englishman and a sex-crazed Japanese anchorwoman. This lets most of the natural-born newscasters (presumably including those who wind up hawking this movie) neatly off the hook.

Back in the 60s, when a few young studio directors were dropping acid and imported gurus like Alexandro Jodorowsky were reading Artaud or Marshall McLuhan, then recapitulating the worst ideas of the avant-garde as if no one had ever thought of them before, such anarchic efforts occasionally had a goofy kind of short-term allure, if one was stoned enough or hungry enough for random kicks. Maybe that’s why this movie is finding its share of defenders among Stone’s contemporaries: it reminds them of their youth. Or maybe they’re thrilled by the sight of Juliette Lewis seducing a boy on the hood of a car, then shooting him to smithereens because he gives such lousy head; the movie abounds in such nifty moments and one-liners.

I suppose one could find an ingenuous charm in the way Stone dives into this material as if it were uncharted territory, and in his assumption that a heavy-handed satirical treatment of media exploitation is itself distinguishable from media exploitation. In order to take such a stance, he’s not really required to say anything fresh or even to find a fresh way of saying something shopworn. He just has to find/create the appropriate journalistic occasion — specifically, the kind that money can buy.

Given the media world in which Stone’s been swimming for the last several years, it’s easy enough to see how he could arrive at this conclusion. Whether the press praised or attacked JFK, it was treated as a journalistic scoop, provoking editorials and front-page stories everywhere from the New York Times to the tabloids, not because it had any important new information to impart — most of its theories about the Kennedy assassination had been in print for years — but because it was an expensive studio release, complete with jivey technical razzmatazz. In JFK Stone worked hard to dissolve the usual distinctions between documentary and docudrama, splintering material into crazy-quilt patterns, alternating black-and-white footage with color, film with video, 35-millimeter with 16 and Super-8, archival footage with re-creations. All this had nothing to do with clarifying his arguments and everything to do with juicing them up to a hysterical pitch, but obviously the experience had lasting effects on his work.

Marx’s observation that history tends to repeat itself “the first time as tragedy, the second as farce” may help to account for the evolution from JFK to Natural Born Killers. One might have assumed, however, that the tragic myth Stone was aiming for in the first film and the satiric farce he’s attempting here would require somewhat different styles, but in fact most of Natural Born Killers looks like a parodic vulgarization and intensification of JFK. (“They liked it before, so maybe they’ll like it again.”) This time, however, Stone seems to be asserting that his helter-skelter montage is the channel-surfing equivalent of what the media as a whole is already doing. Of course, Natural Born Killers is supposed to be a deadly critique of the media, but that’s the kind of circular reasoning one has come to expect from the Hollywood virtual-reality bank — satire as celebration, or vice versa. This time, however, the degree to which Stone carries out this manic duplicity is much more staggering. It’s hardly a surprise to find him in the press book proudly ranking this movie on the subversion meter alongside Kubrick (A Clockwork Orange), Buñuel-Dali (Un chien andalou), Eisenstein (Potemkin), Swift, Voltaire, and even the Greek tragedians (for their “buckets of blood and gouged-out eyeballs”). Why Pee-wee Herman and William Blake didn’t make the final cut in this pantheon is a question well worth pondering.

Natural Born Killers does provide a few very small pleasures not readily available elsewhere. One can see Tommy Lee Jones (playing a prison warden) persuaded to act like one of the Three Stooges, and Lewis and Harrelson so stripped of their talents that they could be performing in a high school audition. (Lewis was allowed or encouraged not to shave her armpits, and Stone reminds us of this “subversion” whenever he has a spare minute, which is fairly often.) One can see elaborate rear-projection and front-projection special effects carried out with considerably less craft and imagination than in bargain-basement independent efforts by Mark Rappaport and Hans-Jürgen Syberberg, “bad” editing matches that suggest an effort to ape certain experimental filmmakers without any sense of their rhythm or taste, and a general aesthetic blindness usually found only in the worst student filmmakers. One can see a wise, sinister old Indian in a hallucinogenic, snake-ridden sequence who bears a striking resemblance to Stone himself, and a credit for the film’s “story” to Quentin Tarantino. In short, all the things that money can buy — or sell, for that matter.