From the Chicago Reader (January 21, 1994); reprinted in Movies as Politics. “Special greetings to Jonathan Rosenbaum, who wrote a very perceptive note on THE LAST BOLSHEVIK,” Chris Marker kindly emailed John Gianvito a little over nine years ago. So I didn’t know how to respond to the news of his sad death, which occurred the day after his 91st birthday in 2012, except to reprint the note he was referring to, as well as a photo of the two of us the only time we met, at Peter von Bagh’s Midnight Sun Film Festival in Finland in 1998 — actually a blurry frame enlargement from Peter’s Sodankylä, Forever. — J.R.

***

**** THE LAST BOLSHEVIK

(Masterpiece)

Edited and written by Chris Marker.

It seems central rather than incidental to the art and intelligence of Chris Marker that he studiously avoids the credit “directed by . . . ” A globe-trotting French filmmaker whose only work of pure fiction with actors is a classic SF short consisting almost exclusively of still photographs (La jetée, 1962), he appears to avoid obvious fiction only in the sense that he finds actuality more than enough grist for the endlessly turning mill of his irony and imagination.

It’s tempting to speculate about whom or what he might identify as the “director” of such Marker masterpieces as Sans soleil (1982) and The Last Bolshevik (1993). “The 20th century” seems a likely guess, for part of the meaning in both these alluring works of wisdom is the ambiguity of causes, of agency, of direction itself, in the dreams and nightmares of contemporary history — the issue of who is doing what to whom. Brilliant works of indirection, they employ narration written by Marker but spoken by someone else, as if the only route to truth was through intermediaries and filters. (To complicate matters further, in Sans soleil the narration is delivered by a woman, recounting letters sent to her by a man.) In the graceful English versions of these works the translation provides another form of mediation, as do the various transfers between film and video within each work. Sans soleil is a film and The Last Bolshevik is a video, but both make plentiful use of both media. Indeed, the incredibly rich palette of textures, lights, and colors Marker discovers in video in The Last Bolshevik (playing this weekend and next at the Film Center) sets new standards for the medium’s beauty and expressiveness.

Born Christian Francois Bouche-Villeneuve in France in 1921, Marker spent his early 20s as a resistance fighter and as a parachutist in the U.S. Army. Prior to making his first film in 1952, he was a published novelist, poet, and journalist, as well as a playwright, though thanks mainly to his studied elusiveness — including his avoidance of photographs and interviews — it’s difficult to learn any particulars about this work today. (He has also worked as an editor for the prestigious literary publisher Editions du Seuil, which brought him in contact with other Left Bank filmmakers who’ve been his contemporaries, friends, and sometimes collaborators, such as Alain Resnais, Agnes Varda, Jacques Demy, and William Klein.)

Surely the most pertinent aspect of this background is that Marker was an accomplished writer before he became a filmmaker–and that he remains a writer in his films. For writer Philip Lopate, a specialist in the personal essay who also happens to be a movie buff, Marker is “the one great cine-essayist in film history,” and it’s easy to see why: among other things, Marker “has the essayist’s aphoristic gift, which enables him to assert a collective historical persona, a first-person plural, even when the first-person single is held in abeyance. Finally, he has the essayist’s impulse to tell the truth: not always a comfortable attribute for an engage artist.”

There’s a wonderful French expression with no easy English equivalent, esprit de l’escalier, and it’s profoundly a writer’s dilemma: the experience of thinking of something to say after the perfect moment to say it has passed. (The expression translates literally as “staircase wit” or “after wit” — the kind of wit that comes to mind as one is leaving, heading down the stairs.) Marker’s artistic persona in his essay films is typically split between his identity as a spontaneous, roving cameraman and his identity as a writer thinking and reflecting much later about what he’s shot. This utopian control over the flow of time permits all sorts of mots justes that would never occur to anyone on the spot. I’ve never seen Si j’avais quatre dromadaires — Marker’s 1966 feature consisting of still photographs taken in 26 countries over ten years, accompanied by three voices representing the photographer and two of his friends — but it’s hard to forget his surreal evocation of a 1959 U.S. exposition in Moscow that figures in the narration: “Abraham Lincoln married Marilyn Monroe and they had lots of little refrigerators.” (This comes from Commentaires, a two-volume collection of Marker’s illustrated film commentaries published by Seuil during the 60s, including commentaries for two imaginary documentaries about the U.S. and Mexico he never got around to making.)

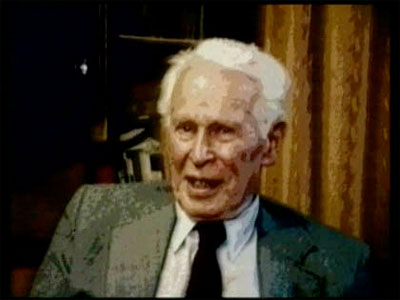

In a tradition of guarded intimacy that seems classically French, the province of writers ranging from Proust to Barthes, Marker develops a relationship with his audience that is at once confessional and secretive: we are made to feel simultaneously that we know him well and that we don’t know him at all. Not surprisingly, a similar relationship develops between us and the central figure of The Last Bolshevik, the Soviet filmmaker Alexander Medvedkin (1900-1989), whom Marker clearly regards as a friend and mentor. The video, divided into two parts — “A Kingdom of Shadows” and “Shadows of a Kingdom” — takes the form of six letters addressed to Medvedkin posthumously interlaced with Medvedkin himself speaking in interviews. The portrait of the Russian filmmaker that emerges is novelistic in its gaps and ambiguities rather than masked or coy, as Marker’s self-representations sometimes appear to be.

A superficial reading of this video — a characteristic example is in the September 1993 issue of Sight and Sound, the English film magazine — would describe it as a simple documentary about Medvedkin, a neglected figure in the Soviet Union and elsewhere. Certainly it is that, though this doesn’t exhaust its ambitions or achievements. More profoundly, it’s a contentious essay on the history of Soviet cinema and the Soviet Union itself; beyond that it’s a multifaceted self-portrait and autocritique by Marker of what it has meant to be a committed leftist for most of this century. The subject of The Last Bolshevik is what it meant to be a communist — and what it means to think about communism today.

But it isn’t enough to say that this video — whose French version is entitled Le tombeau d’Alexandre (“Alexander’s Tomb”) — is about the taste of ashes in Marker’s mouth, though that is part of its resonance. On some level, when Marker is asking who Medvedkin was, what happened to him, and how we can judge him today, he’s asking the same questions about the left in general and himself in particular. Some of these questions, to be sure, have to be read between the lines. It helps if one knows that when Marker first discovered Medvedkin’s work, just before May 1968, a watershed in French utopian thinking, he was part of a French filmmaking collective called SLON, or Societe pour le Lancement des Oeuvres Nouvelles (Society for Launching New Works), which he founded in 1966 and which subsequently adopted the name Group Medvedkine. This appropriation of the name of the one Soviet filmmaker who, as Marker expressed it, put “the camera in the hands of the people” led to SLON distributing Medvedkin’s most famous feature, Happiness, in France in 1971 and making a half-hour short, The Train That Never Stops, to introduce it. (Much of this short consists of an interview with Medvedkin, and many excerpts from it are in The Last Bolshevik.) Yet significantly, SLON is not mentioned once in the video, and use of first person plural is kept to an absolute minimum. By implicitly reducing his former collective to “I” much of the time, Marker seems to be dismissing aspects of his own activities, and the dark implications of this dismissal are as disturbing as the doubts he sows about the grotesque, perhaps obligatory, compromises of Medvedkin and some of his colleagues during the Stalinist period.

Above all, like Sans soleil, The Last Bolshevik is a reflection on what it’s like being on this planet at this particular moment — a reflection that’s both poetic and practical, passionate and considered. One of the key dilemmas of living in the 90s is the task of trying to distinguish information from advertising in all walks of life, yet that has been a central problem in Soviet art for most of this century, as Marker shows here. Most of what we remember about Potemkin and regard as history, from the shooting of sailors under a tarpaulin to the Odessa Steps massacre, is the invention of Sergei Eisenstein, and some of the most famous photographs used to represent and “authenticate” the Russian Revolution prove to be restagings. As George Steiner puts it in the video’s opening epigraph, “It is not the literal past that rules us: it is images of the past.” In fact, The Last Bolshevik is not so much ruled as haunted by images of the past.

Early on in the video we see Medvedkin in a 1984 interview saying, “I intend to go on living as long as possible. I don’t mean until the 21st century, but another five years would be nice.” “And five years later you died,” the narrator (Michael Pennington) remarks. “The first five-year plan that ever worked.”

One five-year plan of my own has been an ongoing effort to persuade the Film Center or Facets Multimedia to book a subtitled print of Lev Kuleshov’s The Great Consoler (1933) from the British Film Institute in London — a mind-boggling feature about O. Henry, in prison for embezzlement, writing a story about safecracker Jimmy Valentine that later radicalizes a shop girl. It’s long been my suspicion that the most exciting wave in Soviet cinema came not during the 20s, as is generally believed, but in the early 30s, before the Stalinist crackdowns, when most of the major directors were making their first talkies: Vertov (Enthusiasm), Dovzhenko (Ivan and Aerogard), Pudovkin (Deserter), Kuleshov (Horizon and The Great Consoler), and others. For a brief period, before the tenets of socialist realism took hold, communist idealism and radically innovative art were allowed to rub shoulders, and we still haven’t begun to deal with the dazzling results (alas, many of the best of these films are virtually unknown in the West).

Medvedkin’s Happiness — which comes at the tail end of this period (1935), the last silent Soviet picture — clearly belongs to this ferment. It’s a pity the Film Center isn’t showing it in conjunction with The Last Bolshevik, but fortunately this wild hour-long comedy, excerpts of which are seen in The Last Bolshevik, is available on video from Kino International and a few specialized rental outlets, such as Facets Multimedia. Surrealist satire and slapstick with a hilarious hick hero, it starts off with peasants looking through a knothole in a fence at the easy life of a czar — fruit dumplings leap off a plate and dive into his mouth. Things only get goofier and more outrageous: nuns are depicted erotically, priests hysterically wrestle one another for rubles, a tractor runs amok, an entire house creeps like a centipede across a landscape. When the hero, repeatedly foiled in his quest for simple happiness, decides to commit suicide and starts building his own coffin, the cossacks are indignant: “Who permitted you to die on your own? . . . Who authorized you to take death without leave?” Later a woman tries repeatedly to hang herself from a windmill, and the results are even more grotesque.

Happiness gives us a fair sample of Medvedkin’s gifts as a director, and Marker gives us clips from many of his other surviving works, including some striking camp extravaganzas that followed Happiness. (Most memorable are The New Moscow — a sound comedy of the Stalinist era with Busby Berkeley-like sets, a magical fireworks display, and a creeping skyscraper — and a subsequent rural musical featuring cows in boots.)

But Medvedkin’s importance is only marginally connected with the on-screen evidence, which may help to account for why his name is missing from most movie reference books. His most important work — done just before he made Happiness and grounded in burlesque performances he staged as an officer during the civil war in which actors dressed up as horses to protest the mistreatment of animals — was running an unpublicized revolutionary project known as the “film train.” This train–three railway cars that housed a sizable film crew and allowed them to store equipment and process, edit, and screen movies — traveled back and forth across Russia, making silent comedy shorts with various peasant collectives that were designed to address their particular problems. The film train made as many as 72 shorts in a single year, yet none of them were believed to have survived. However, nine of them were recently discovered, and we’re treated to samples in The Last Bolshevik.

But the important thing about the film train as a concept isn’t so much what it yields today in terms of films as what it signified then. As Marker puts it, citing a Chinese proverb, “Give a man a fish and you feed him for one day. Teach him how to fish and you feed him for life. . . . You [i.e., Medvedkin] wouldn’t give people films, you’d give them cinema.”

By the same token, one might say that what Marker gives us is neither a video nor a film, but an exciting new means of expression — the beginning of a dialogue and discussion that flies in the face of the received wisdom that we can now safely put the 20th century behind us. After the glibness, the dullness, the despair we hear about the death of communism, of utopia, of idealism just about everywhere we turn, in the pages of the Nation as well as the National Review, Marker reminds us, even in his own disillusionment and bitter irony, that we’re much too eager to bury a history and a legacy we never really understood in the first place. Communism is over? Very well then: let’s take a good, hard look at what we’ve decided to dismiss. And weep, as Medvedkin once did when he found he could put two pieces of film together and have it mean something. “Nowadays,” Marker reminds us, “television floods the whole world with senseless images and nobody cries.”