From the August 17, 2001 Chicago Reader. –J.R.

Apocalypse Now Redux

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Francis Ford Coppola

Written by John Milius and Coppola

With Martin Sheen, Marlon Brando, Robert Duvall, Frederic Forrest, Albert Hall, Sam Bottoms, Laurence Fishburne, Dennis Hopper, G.D. Spradlin, Harrison Ford, Colleen Camp, Cynthia Wood, Christian Marquand, and Aurore Clement.

It’s hard to think of many movies where the great, the not so great, and the simply awful coexist quite as brazenly as they do in Apocalypse Now. This was true in 1979, when the movie clocked in at 150 minutes, and it’s true 22 years later, when the new version, Apocalypse Now Redux, runs a third longer.

If anything, the longer version — not so much a rethinking of the material as an expansion, with a minimum of reshuffling, by the adept Walter Murch, who also worked on the original — is better and worse, emphasizing both the ambitious scope and the fatal flaws of Francis Ford Coppola’s achievement. Among the more substantial additions are a ghostly sequence set on a French plantation (featuring Aurore Clement and the late Christian Marquand) that tries, with mixed results, to poeticize the futility of outsiders, French or American, getting involved in the Vietnam war and a silly and rather inconclusive sequence involving a couple of Playboy Playmates (Cynthia Wood and Colleen Camp) that adds nothing. We also get to hear more of Kurtz (Marlon Brando) rattling on and even reading choice excerpts from Time magazine to a nearly comatose Willard (Martin Sheen).

Some critics have claimed that this is the best new movie we can expect to see this year, an idea so revolting I can only wonder about the ideological desperation that produced it. (One more excuse to stay away from everything but Hollywood products?) I’ll grant that the expanded movie is processed in glorious Technicolor (which Hollywood abandoned for obscure reasons just after The Godfather, Part II — though you can still find it in some Chinese and Korean pictures because the equipment was sold to various Asian production facilities). I’ll grant that Murch’s sound work here is some of his best, that Michael Herr’s narration is the second-best thing he’s written (after Dispatches, the nonfiction book about American combat in Vietnam that got him the assignment in the first place), and that Coppola’s direction is full of superb environmental (i.e., theme-park-ride) effects. I’ll even grant that these and related virtues are superior to what we can find in contemporary Hollywood blockbusters, though I realize this isn’t saying much.

Still, to imply that this movie’s highly entertaining obfuscations of American and Southeast Asian history have more value than anything filmmakers could possibly tell us today is to place a pretty low premium on the truth, the world, and the present — not to mention movies and ourselves. I keep hearing that this movie is supposed to provide some definitive kind of statement about Vietnam — what it was, what it means, and so on. But considering that Vietnamese people aren’t given even a hint of a voice in the statement — an absence that goes entirely unremarked — this is monumental chutzpah.

Five years after this country pulled out of Vietnam — relieved, though not admitting defeat — seeing Coppola’s movie as some sort of ideal to aspire to was justifiable, or at least understandable. Clinging to it as that today is tantamount to pulling a blanket over our heads.

Maybe I’m being hard on this movie because I feel implicated, and maybe I feel implicated because it gets to me. Like Taxi Driver, another “incoherent text,” as critic Robin Wood might say, that came out only three years earlier, it makes random slaughter look romantic, spectacular, and downright artistic — so goddamn cinematic you can tap your toe to it. It opens with a frank illustration of how beautiful a tropical jungle silently exploding into flames can look, especially when the explosion is combined with a tune by the Doors that follows the spiffy stereo effect of helicopter blades faintly whipping past. “Far out,” we’re tempted to say, helped immeasurably by the fact that the filmmakers have thoughtfully shielded us from seeing whether human flesh is being devoured by the napalm. After all, this is entertainment we’re talking about.

In 1980 Pauline Kael wrote, with some justice, “Trying to say something big, Coppola got tied up in a big knot of American self-hatred and guilt, and what the picture boiled down to was: White man–he devil.” (Unfortunately, she never got around to explaining what a more appropriate sentiment regarding American involvement in Vietnam might have been, though I think we can safely assume she wasn’t espousing pride or indifference.) Yet when we watch the exhilarating spectacle of the deliciously loony Colonel Kilgore (Robert Duvall) bombing villages to the strains of Wagner while indulging his enthusiasm for surfboards and delivering instantly quotable lines such as “I love the smell of napalm in the morning,” we may laugh or cringe, but I don’t think our response corresponds to “White man — he devil.” Indeed, the spirit of John Milius’s original conception is much closer to “White man — he hot shit.” And to be fair, Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness,” Milius’s main source of inspiration, is founded on much the same mixture of guilty-liberal anticolonialism and protofascist awe.

One of the first articles I ever published was an essay for Film Comment on Orson Welles’s first film project, whose conception, screenplay, designs, and tests occupied him during his first six months in Hollywood, before he started his preparatory work with Herman Mankiewicz on Citizen Kane. It was a contemporary adaptation of “Heart of Darkness,” with an experimental use of a subjective camera to represent the viewpoint of Marlow, the story’s somewhat detached narrator — to be played mainly offscreen by Welles, in his storytelling radio persona — as he penetrates the heart of the African jungle in his search for Kurtz, a crazed white ivory trader who’s lording it over the natives. Welles updated the story to relate it to contemporary fascism in Europe — focusing on Kurtz as a charismatic, proto-Nazi despot before Kane was even a gleam in his eye — and RKO halted the project, finding it both too expensive and too commercially risky. (Welles had already adapted the story, rather lamely, for radio in 1938 and would readapt it for that medium much more effectively in 1945. I believe that parts of both versions can be heard briefly in the 1991 documentary Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse.)

Working on my article in Paris, armed mainly with a copy of Welles’s script, I impulsively wrote to him — he was there editing F for Fake — and had the staggering good fortune of being invited to lunch by him two days later. He told me, among other things, that he’d reluctantly decided to play Kurtz because he hadn’t found anyone else for the part. “I’m still looking,” he said wistfully, after vowing he’d never truly abandoned the project. He also said that he’d originally wanted to shoot the film in either South America or Africa. Clearly the self-interrogation of charismatic authority that had informed his celebrated modern-dress stage production of Julius Caesar in 1937, complete with piercing shafts of “Nuremberg lighting” — and would subsequently inform his ambivalent portrait of Kane, some of it shot with similar lighting — would have got an exhaustive workout in his “Heart of Darkness.”

My article appeared, along with a script extract, in late 1972, two years after Milius had written a draft of the Apocalypse Now script for George Lucas at American Zoetrope and two years before Coppola, coming off The Godfather, Part II, decided to direct it. Milius had written a screen adaptation of Conrad’s novella in 1965, so I’m not trying to suggest that my article influenced anyone. But various sources have confirmed that the filmmakers were well aware of Welles’s project, and the film shows many traces of his influence, including a frequent use of Nuremberg lighting and the early upside-down close-up of the head of Sheen’s Willard — this movie’s Marlow equivalent — which duplicates the opening shots of both Othello and The Trial. Some of the newly added footage in Redux, showing children laughing at Willard through slats in his cage, can be traced back to another creepy sequence in The Trial.

To confuse matters, the ironic, wisecracking offscreen narration of Willard, written by Herr, may show more signs of Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe than it does of Conrad’s Marlow. Willard has been enlisted as a mercenary to “terminate” Kurtz, an American officer fighting in Vietnam and Cambodia who’s gone murderously insane, and as Willard pages through the man’s dossier during his long journey, he implicitly becomes a kind of private detective attempting to solve the “mystery” of the man. Could this be because the American “translation” of Marlow as a mediating moral consciousness somehow leads us to the more noirish figure of Chandler’s hero? Whatever the reason, this isn’t the first time such an arresting thematic and stylistic sea change has taken place in American movies. In 1946 Welles’s innovative subjective-camera idea was finally used throughout an entire Hollywood feature, Robert Montgomery’s clunky Chandler adaptation Lady in the Lake. Montgomery missed the whole point of Welles’s interest in the device — as a way of dramatizing Marlow’s and the audience’s ambivalent attraction-repulsion response to Kurtz. In Apocalypse Now, the shift from Marlow to Marlowe seems more defensible, at least as long as Willard qualifies as a moral commentator on what he’s observing, as someone who can voice the viewer’s questions — such as why Kurtz is deemed crazy by the U.S. military and Kilgore is not.

Willard ceases to function as a plausible moral commentator relatively late in the film, after the jittery crew on his patrol boat — a crew we get to know much better in Redux than we did in the shorter version; it consists of Clean (Laurence Fishburne), Chief (Albert Hall), Lance (Sam Bottoms), and Chef (Frederic Forrest) — mow down an innocent Vietnamese family in a passing boat. Learning that a hidden puppy was the cause of the mother’s “suspicious” behavior, the crew is confused and horrified by what they’ve done. Then they discover that the mother is still alive. Chief wants to get her to medical help, at which point Willard steps forward and puts a bullet through her head, explaining that he’s in a hurry to get to Kurtz.

This scene — along with a much earlier one, when Coppola cuts suddenly and briefly from Kilgore blasting Wagner from his armed helicopter to a quiet Vietnamese village with a flock of children filing across a schoolyard, shortly before bombers arrive — is one of the few in the film that force us to contemplate some of the worst aspects of what the war was doing to the Vietnamese. And because it is the character we most identify with who delivers the coup de grâce — deliberately, efficiently, and callously, rather than confusedly, ineptly, and innocently, like the preceding slaughter by the crew — our emotional relation to him is permanently altered.

This is even acknowledged in the pointed narration from Willard that we hear over the next linking sequence — a rationalized explanation for his behavior: “It was a way we had over here of living with ourselves. We’d cut ’em in half with a machine gun and give ’em a Band-Aid….It was a lie. And the more I saw of them, the more I hated lies….Those boys were never going to look at me the same way again.” Whether or not these can be taken as words of truth or wisdom, the film can only fall apart as a moral investigation afterward, because Willard is no longer asking questions — like Kurtz, he’s only answering them. In the Conrad story Kurtz’s solution at one point is to scrawl “Exterminate the brutes”; in the movie, the inscription is slightly less pointed, though it’s in red ink: “Drop the bomb! Exterminate them all!”

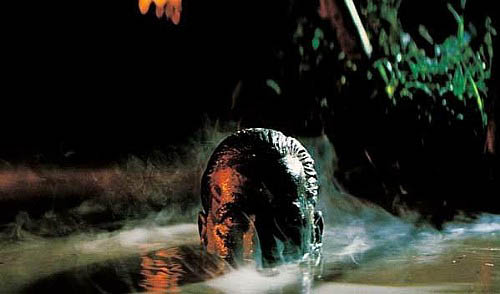

Coppola too has started trying to answer rather than ask questions. In the extended closing sequence, when he has to put up or shut up about Kurtz, he finally hedges his bets by trying to do both, producing Brando (as one might produce a parade float), a lot of lousy dialogue, and a heap of literary references instead of a character or any ideas worthy of the name. Kurtz’s speeches seem designed to sound on some occasions saner than anything else heard by Willard on his journey and on other occasions downright psychotic (“We have to kill without judgment — for it’s judgment that defeats us”). Sometimes they sound liberal, sometimes fascist. Presumably this makes him all things to all men. The nadir is reached when, in swift succession, the film serves up Kurtz’s recitation of T.S. Eliot’s “The Hollow Men”; a shot panning down to Kurtz’s copies of the Bible, From Ritual to Romance, and The Golden Bough; a hokey scene in which Willard rises from a pool of slime; the on-screen slaughter of a carabao (a Filipino ceremony observed by Coppola) intercut with Willard’s mainly offscreen slaughter of Kurtz; the local savages kneeling down before Lord Willard (in a set that evokes the African village in King Kong), then laying down all of their arms when he drops his own weapon (which gamely proposes the nihilistic American mercenary and slime artist — Kong’s Carl Denham, in short — as the ultimate peacemaker in Southeast Asia: murderous white man — he Zeus, P.T. Barnum, Jesus, Gandhi, Martin Luther King, and Martin Sheen all rolled into one). This disgusting slag heap of macho pretension, posturing, and lies is anticipated in an earlier monologue by Kurtz crediting the Vietcong with an invented atrocity — cutting off the arms of children who’ve just received polio vaccines from saintly Americans — that we’re all humbly invited to see as a succinct explanation for why America was losing the war.

Still, even this lineup is less offensive than the racist xenophobia of The Deer Hunter, expressed through the contrivance of a sadistic game of Russian roulette used by the Vietcong to torture people. That movie copped a slew of Oscars in 1978 and is still regarded as respectable, beautiful, and honorable in some quarters, not all of them American. I remember thinking when Michael Cimino went to pick up his prize that he should have said, “I’d also like to thank the contributions made by many thousands of Vietnamese and American corpses, without whom none of this would have been possible.” Compared to that movie — which simply blames evil Vietnamese bullies for destroying the souls of innocent Americans — Apocalypse Now deserves our respect.

Perhaps a permanent flaw in the story’s construction — whether it’s by Conrad or by Milius and Coppola — is the aforementioned narrative shift from question to assertion (“The horror! The horror!” Kurtz gasps while dying, and the film can only repeat this piece of vagueness), from mystery to rhetorical pseudosolution, from traveling up the river and thinking about Kurtz to meeting him in the flesh. Even if he’s kept in shadows, literally as well as metaphorically, to preserve and perpetuate the movie’s neo-Wellesian sense of expressionist rhetoric, Kurtz’s belated appearance can only seem anticlimactic, and the same is true in Conrad’s story.

Some recent commentators have attacked Herr’s narration for its literary posturing, but his rhetoric isn’t any more overheated than the superb cinematography by Vittorio Storaro or Murch’s druggy audio effects. Those effects, like the ones in Coppola’s earlier film, The Conversation (1974), probably qualify Murch as a coauteur; what he does in the opening sequence — getting us from helicopter blades to the blades in a ceiling fan — is as ravishing as any of the lap dissolves. Literary or not, Herr’s hyperbolic prose, here and in Dispatches, may be the best writing we have about American combat in Vietnam. That he wrote all of the narration during the film’s long postproduction — in effect, trying to locate as well as articulate the film’s ethical positions only after Coppola returned from the Philippines to California with his endless footage — only throws into relief the fact that he was apparently the only creative person working on the project who had had any experience in Vietnam. Obviously he can’t undo the unredeemable pretensions of Milius and Coppola’s screenplay, but he does ask enough of the right questions to get us to contemplate our relationship to this material, though this strategy works, as I’ve already argued, only as long as Willard’s questions remain unanswered.

Should we conclude that any ending for this tale would have to be unsatisfactory? That’s what most commentators, including me, have generally maintained. But the late Serge Daney, who had a somewhat wider frame of reference when it came to American cinema, believed the filmmakers had other dramaturgical options.

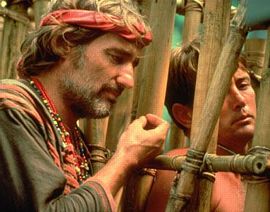

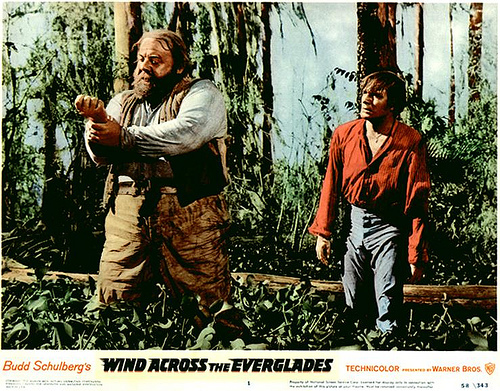

Writing about the film in Cahiers du cinéma, where he was editor, Daney recalled Wind Across the Everglades — a neglected 1958 Hollywood feature directed by Nicholas Ray, written as well as produced by Budd Schulberg, and set in the Florida Everglades in the early part of the 20th century. It’s an ecological parable in which a Willard- or Marlow-like hero (Christopher Plummer) penetrates the primeval swamp to bring to justice a Kurtz-like outlaw named Cottonmouth (Burl Ives), who kills birds in order to sell their plumage. Unlike Apocalypse, this film got better and sharpened its focus once the hero met his prey and the two fell into a tense, uneasy rapport. Their friendship was developed dramatically and logically rather than simply rhetorically, as a retreat from the issues posed, and it culminated in an all-night drinking session for the men, though they became adversaries again in the morning. (Ray’s 1959 The Savage Innocents — which tells a similar tale, this time in relation to Inuit culture — proves that he understood this story better than anyone.)

By Daney’s reckoning, we never believe Willard and Kurtz are doppelgängers who identify with each other, so the ending of Apocalypse remains theoretical. Ives and Plummer may be more limited in some respects as actors than Brando and Sheen, yet Wind Across the Everglades succeeds where Apocalypse fails because Ray, a much greater director, finds substance as well as common cause in both his characters. In Wind Across the Everglades this common cause is protest, but the only thing Willard and Kurtz seem to share is an abstraction: “The horror! The horror!” Maybe this is because they themselves are both ultimately abstractions who never get beyond their narrative functions; they can explain the story perhaps, but not our relation to it. Some people might be scandalized by Daney’s preference (and mine) because they’ve never heard of Ray’s film. They can’t go trundling off to the video store expecting to find it and decide for themselves (Warners often doesn’t know what it has), and I can only stress that money and consumerism rather than art or lucidity are responsible.

Also not waiting for us on the shelf is a movie that tells us what we need to know about the Vietnamese. When we hear the word “Vietnam” nowadays, we’re more apt to think about our involvement in that country than about the Vietnamese themselves, whom we’ve never figured out a way of adequately acknowledging — as people, as witnesses, even as spectators of Apocalypse Now Redux. By necessity, this movie is about America, not Vietnam, because America is the only thing we know how to consume. It was designed to express every point of view we might already have about the war without challenging or expanding any of them too much. After all, if it did that it couldn’t have been commercial enough to make its money back. And if its final scenes are incoherent — reaching for metaphysical platitudes instead of some understanding of the countries we were invading — that’s not much different from the way America concluded its own adventure in Southeast Asia.