From the August 14, 1998 Chicago Reader.

The Son of Gascogne

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Pascal Aubier

Written by Patrick Modiano and Aubier

With Grégoire Colin, Dinara Droukarova, Jean-Claude Dreyfus, Laszlo Szabo, Pascal Bonitzer, Otar Iosseliani, Alexandra Stewart, and Jean-Claude Brialy.

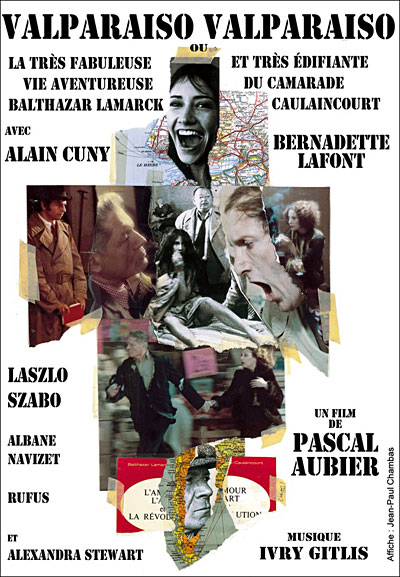

It’s been a full quarter of a century, but I still harbor fond memories of a low-budget French comedy called Valparaiso Valparaiso, a first feature starring Alain Cuny and Bernadette Lafont that I saw at Cannes in 1973. A lighthearted satire about the myopia of romantic French revolutionaries, it details an elaborate hoax perpetrated on a befuddled leftist — a character so absorbed in the glory of departing for Chile to fight the good fight as a special agent that he doesn’t even notice the political struggle going on around him on the French docks when he leaves.

The film was so marginal that two years passed between its completion and its modest premiere at the Director’s Fortnight at Cannes, and you won’t find it mentioned in any of the standard reference books. No, I take that back: Jean-Michel Frodon gives it a third of a sentence in his over-900-page L’Age moderne du Cinéma Français de la Nouvelle Vague à nos jours (1995), linking it with two other films of the early 70s inspired by the French Communist Party and critical of leftists. Valparaiso Valparaiso had the sort of heart and lyricism, however, that lingered in a few post-New Wave movies of that period, and even though the filmmaker promptly dropped out of sight, I still remembered his name 22 years later when I went to see his feature The Son of Gascogne at the Berlin film festival in 1995.

In the question-and-answer session after the screening, I discovered that Pascal Aubier had directed only one other feature between Valparaiso Valparaiso and Le fils de Gascogne — Le chant du départ in 1975 — but had meanwhile made 38 short films for French television. Even more striking to me was the profound continuity I felt between the two features I’d seen. The new film had as much heart and lyricism as its predecessor and also involved an elaborate hoax, one that testified no less eloquently to some cherished nostalgic fantasies of its own period.

Three months later, The Son of Gascogne premiered in France on TV during the Cannes festival. It’s hard to say whether this made it more marginal than Valparaiso Valparaiso or less: even though The Son of Gascogne was probably seen by many more people, it had no critical profile. Aubier’s film did get selected by the New York film festival, however, thanks in part to my enthusiasm for it as a selection committee member; during Aubier’s visit to New York for the showing, he landed a teaching job at New York University and has been based in this country ever since.

The usual lag time for foreign pictures not distributed by large companies has now elapsed, and The Son of Gascogne arrives in Chicago this week, playing eight times at the Film Center. The story concerns a fatherless 18-year-old boy named Harvey (Grégoire Colin) from Le Havre whose mother works as a tour guide for Russians. To help her out, he goes to Paris to host a group of Georgian folksingers arriving by train to give a concert, and winds up courting a Russian-Georgian girl named Dinara (Dinara Droukarova) who’s come along to help them with their French. Shortly after the Georgians’ arrival, a Paris-based Hungarian actor and director (Laszlo Szabo, playing himself) declares that Harvey is a dead ringer for (fictional) French New Wave director Alexandre Gascogne, said to have died in the mid-70s; Szabo is convinced that Harvey is his son.

Harvey, who doesn’t know anything about his father’s identity, has never heard of Gascogne and is pretty skeptical about the whole idea. But when the group’s chauffeur — a small-time con artist named Marco (Jean-Claude Dreyfus) — decides he can parlay this fancy into a moneymaking scheme and starts to introduce Harvey to Gascogne’s former friends and colleagues, Harvey is drawn into the hoax and even begins to entertain the possibility it might be true. The scheme involves a legendary “lost” film by Gascogne called Chaleurs (“Heat”), allegedly shot shortly before his death but hidden away ever since in some lab due to unpaid bills.

Over the course of a few days Harvey, Dinara, and Marco encounter a host of New Wave veterans and associates, playing themselves: actors including Yves Alfonso, Anémone, Stéphane Audran, Jean-Claude Brialy, Bernadette Lafont, Macha Méril, Bulle Ogier, Marie-France Pisier, Alexandra Stewart, and Marina Vlady; directors including Claude Chabrol, Michel Deville, Otar Iosseliani, Richard Leacock, and Jean Rouch; and other figures from the French film world, including producer Pierre Cottrell and historian Bernard Eisenschitz. (One of the few fictional roles is played by Pascal Bonitzer — a critic, a screenwriter for Raul Ruiz and Jacques Rivette, and, based on his own recent first feature, Encore, an able director.) The Son of Gascogne also employs a fair number of clips from New Wave films like Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless and Agnes Varda’s Cleo From 5 to 7 (both reenacted by Harvey and Dinara as they walk around Paris) as well as Chabrol’s Les bonnes femmes, and it makes many references to other New Wave figures like Anna Karina, Eric Rohmer, and Jean Eustache.

So the film is pungent with nostalgia, but Aubier is after something meatier as well: he’s more concerned with the meaning of these memories in the present than he is with the memories themselves. And one way of differentiating The Son of Gascogne from Valparaiso Valparaiso is that his allegory about the myth of the New Wave and the meaning of postmodern pastiche is a good deal more tender and forgiving about innocence than its predecessor: Aubier asks us to sympathize not only with the romanticism of an older generation but with the frustrations of a younger one reduced to bluff and imitation in trying to live up to that heritage.

The film offers a highly personal take on the myth of the New Wave: the two glimpses we have of “Gascogne,” in photographs from the 60s, are of Aubier himself. In one, he’s standing alongside Stewart, Iosseliani, Méril, and Karina in Moscow; in another, he’s leading a street demonstration in May 1968. In fact, Aubier published a full-length book a couple of years ago, Les mémoires de Gascogne — a personal scrapbook of photographs and documents combined with an extended dialogue between Aubier and Eisenschitz detailing the complex interface between this movie and Aubier’s various activities in film and politics over three decades.

If this makes the movie sound specialized and self-indulgent, the foregrounded and highly touching story of Harvey and Dinara mitigates that tendency and testifies to the filmmaker’s generosity rather than his self-absorption. He’s interested above all in the current residue and significance of these past events: his encounter between two 18-year-olds from Georgia and France has more in common with Richard Linklater’s Before Sunrise than it does with François Truffaut’s Day for Night because ultimately Aubier is more concerned with love in the 90s than he is with cinema in the 60s.

At its best, the movie draws on both at once for its resonance: Dinara’s earnest struggle to master French harks back to Jean Seberg in Breathless, and Harvey’s heartfelt defense of the hoax for the excitement it’s brought to his life recalls the passion of Jean-Pierre Léaud in Truffaut’s early films. Certainly the spontaneous interactions between these two actors — Droukarova is perhaps best known here for her part in Freeze — Die — Come to Life, while Colin may be remembered for his lead part in Olivier Olivier — evoke the New Wave as much as anything else here does.

I can’t guarantee that everyone will be as charmed by The Son of Gascogne as I am because an undeniable part of its appeal is generational. Like Say Anything…, Pump Up the Volume, The Thing Called Love, and Telling Lies in America, it looks at teenage love from the vantage point of someone much older; teenage spectators may feel as removed from Aubier’s fantasies as his teenage couple feel from the New Wave. Yet it’s hard to believe that its emotional surges won’t be shared to some degree by viewers of all ages, because of the film’s tenderness for youth. The Son of Gascogne makes being young seem a lot tougher than being middle-aged — especially if you’re faced, as so many teenagers are nowadays, with the accusation of having been born too late.