From Cineaste, Winter 2020. — J.R.

It’s been almost two decades since I first discovered the fiercely independent, passionately committed, and poetically inflected cinema of John Gianvito via his 168-minute The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein (2001). Later that year, I headed a jury at the Buenos Aires Festival of Independent Film that gave it our jury prize, but it’s mainly had an uphill struggle ever since being seen and recognized, most likely due to both its subject matter and its running time. John points out that I may have previously seen his 1983 feature The Flower of Pain, but if I did, I no longer remember it; ditto his portion of a 1986 episodic feature that he originated, Address Unknown.

The Mad Songs remains my favorite film of his, yet even though it was available for a spell on DVD, it currently lacks a distributor. A powerful act of witness about some of the tragic stateside consequences of the first Gulf War, it was made over a seven-year period, including two years of shooting in New Mexico — despite the fact that Gianvito is a Bostonian, where he currently teaches film at Emerson College and was formerly a curator for five years at the Harvard Film Archive. He also edited Andrei Tarkovsky: Interviews (University Press of Mississippi, 2006), a book that may be better known than any of his films.

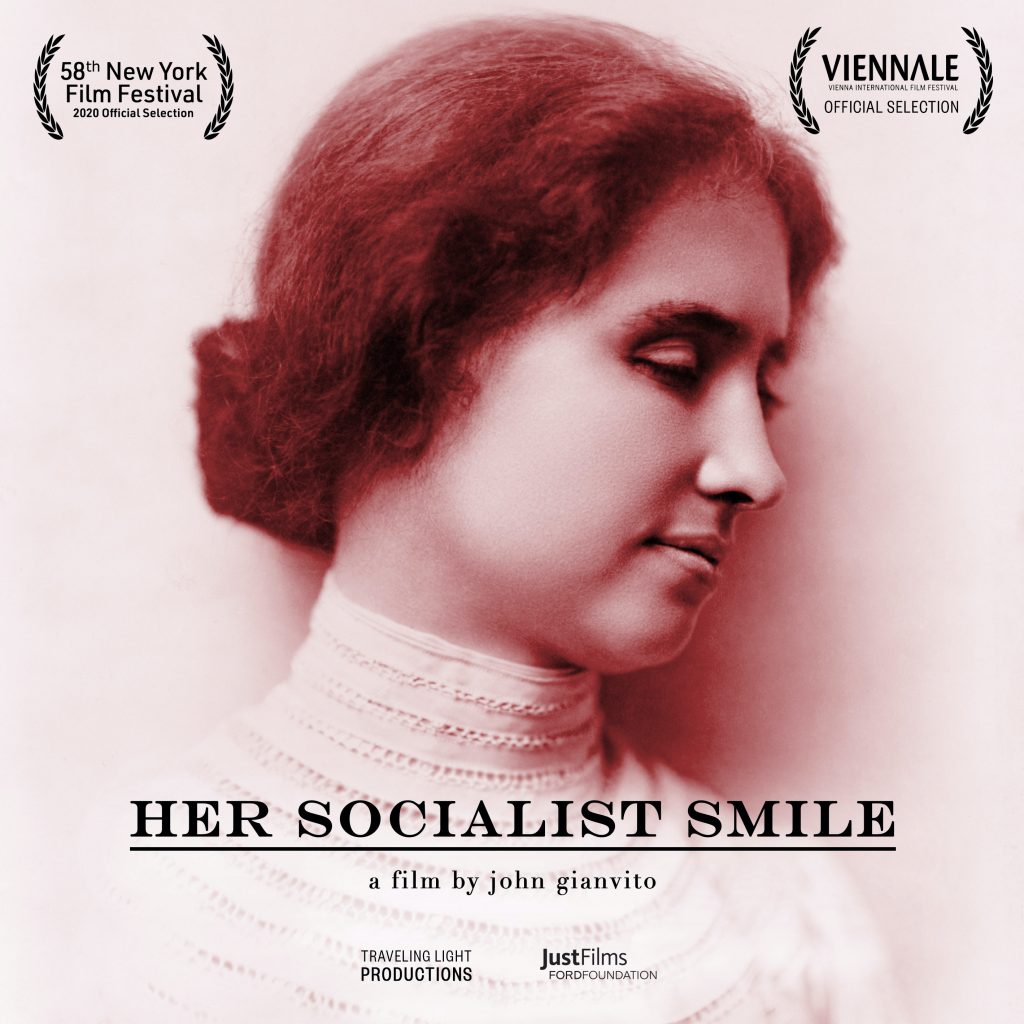

He’s generally had better luck with two of his subsequent features, his experimental documentary Profit Motive and the Whispering Wind (2007), a meditation on the sites of many leftist struggles distributed by The Cinema Guild, and set to be posted shortly by MUBI in an HD restoration; and the 2012 episodic feature Far from Afghanistan — instigated by Gianvito, who contributed a segment featuring Andre Gregory along with other segments by Jon Jost, Minda Martin, Travis Wilkerson, and Soon-Mi Yoo—available for streaming on Amazon via Fandor. And I’m confident that he’ll also fare much better with his latest experimental documentary, about Helen Keller, Her Socialist Smile (2020), which was about to be screened at the New York Film Festival, and the VIENNALE Film Festival when our online conversation took place in August.

But I’m overlooking Gianvito’s even more uncompromising For Example, The Philippines, a nine-hour experimental documentary comprising Vapor Trail (Clark) (2010) and Wake (Subic) (2015), which, like both Mad Songs and Far from Afghanistan, deals with the legacy of U.S. military involvement and everything it entails — in this case, the human ravages left by toxic waste from the Clark Air Force Base and the Subic Naval Base (for almost a century, the two largest U.S. military compounds outside North America) after the Philippine Senate voted to eject them in 1991.

The following exchanges were made via email during the pandemic, with various afterthoughts later added by each of us .— Jonathan Rosenbaum

Cineaste: Part of my fascination with your film relates to how little most people know about Keller’s socialism, as well as the fact that she could see and hear for almost two years before an illness left her deaf and blind. Both of these forms of ignorance seem important to me, because a major part of your film addresses, first, what we mean by “socialism” (which Noam Chomsky addresses, quite brilliantly and usefully, in the film), and, second, what it means to see and hear (or not to see and not to hear). It’s also important to realize how much Keller’s grasp of sight and sound was built on the first months of her life, even though this was a distant memory.

One personal investment I have in Helen Keller is that I was born less than a mile — perhaps even less than half a mile — from Ivy Green, where she was born. I grew up in Florence in Lauderdale County, but Sheffield, Tuscumbia, and Muscle Shoals, all in Colbert County, are just across the Tennessee River from Florence, and I was born in Sheffield because for some reason the Florence hospital had no spare beds. I was reportedly kept there in a bureau drawer because no cribs, cradles, or beds were available. And my grandfather had movie theaters in Sheffield, Tuscumbia, and Athens, two in each town, as well as three in Florence, so I went to Tuscumbia frequently with my father.

Another personal element: my brother Alvin and I spent much of the summer of 1962 in the back lawn of Ivy Green, attending and watching outdoor rehearsals for an on-site production of The Miracle Worker, and many subsequent performances there that summer as well. We had many friends involved in that production, one of whom used to argue with me that the Tennessee Valley Authority, located only a few miles away, couldn’t possibly be socialist because it “worked” — which sounds naive, yet it perfectly matches Chomsky’s account of how both the American and Russian definitions of socialism expediently equated it with the betrayals of socialism.

How did you first become interested in Helen Keller? What did you read first, and what were the other steps that led you to Her Socialist Smile?

John Gianvito: Like many of my generation, while I am sure Helen Keller’s name had been brought up in my Catholic grade school as an exemplar of modern-day “saintliness,” my first conscious recollection is watching Arthur Penn’s film of The Miracle Worker on television when I was probably ten or eleven and which at the time made quite a powerful impression. In part due to some of its aesthetic qualities, so distinct from much of what I would have been watching, as well as the particular strength of Anne Bancroft’s performance as Anne Sullivan.

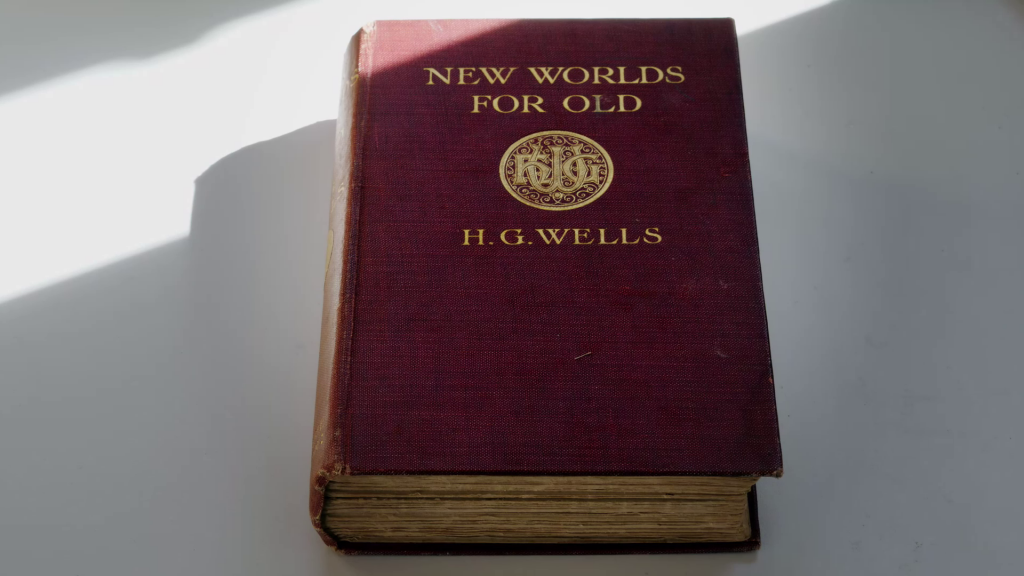

Fast-forward to 2001. Having finally brought my film The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein to completion after seven years of struggle, I was keen to embark on a new venture. Amidst my reading of various works by Howard Zinn, I learned for the first time about Helen Keller’s ardent engagement with socialism and how, much as was done with the popularized images of Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr., her radicalism had been sanitized. I began to track down some of her texts and speeches and found a great deal there to be as germane to the historical moment as when she first wrote them, and it was this that started me exploring the possibility of what I imagined as maybe a short half-hour profile of this unheralded dimension of Keller’s life.

For about a year I undertook, in small steps, research around materials that might bring the concept for such a film to life. I tracked down other documentaries that were made on Keller during her lifetime to see what footage they used, I searched the holdings of the Library of Congress, I started ordering books, I located a tiny handful of audio recordings, and to my dismay I couldn’t seem to find any motion picture, audio, or even photographic evidence specifically documenting her political activities of this period. Helen Keller’s so-called “socialist years” extend roughly from 1909 when, at age twenty-nine, she first joined the Socialist Party in Massachusetts up till 1924 when she agrees to work on behalf of the American Foundation for the Blind [AFB] at which point it appears it was made clear to her that she would have to cease and desist with her militant political advocacy if she was to commit to fundraising on behalf of the blind. It was then that her more pronounced socialist activities and statements subsided, although when you read her letters and diaries it is evident that she never disavowed those views.

What surprised me was the fact that here was this woman who by the time she was eight years old was already world famous, and about whom there exists a vast amount of documentation, and yet across this long swath of time I can’t seem to find anything particularly visual pertaining to her public political endeavors. I then began to suspect that the AFB, as the eventual primary repository of Keller’s archive, may in its initial years of collecting consciously decided not to retain such materials. I had numerous reasons to think this. It is also around this time that I learned about the existence of a secondary archive, the Helen Keller International in downtown New York. As I was getting ready to try to contact them I discovered, as is recounted in the film, the news about the Center’s complete destruction during the events of September 11, 2001. At that juncture, I finally said to myself in regard to the whole project—interesting idea, but for a filmmaker there’s simply not enough here to work with and I moved on.

Fast-forward one more time, to 2015. I had just finished my film Wake (Subic), and I was mulling about in pursuit of a new idea for a project and thoughts around the Helen Keller film started to resurface. I heard a voice in my head prodding me, “So you want to make a film about the most famous blind and deaf individual and you have no images and no sounds. That’s actually an interesting creative challenge and you shouldn’t shy away from it.” With that thought, I began the film in earnest.

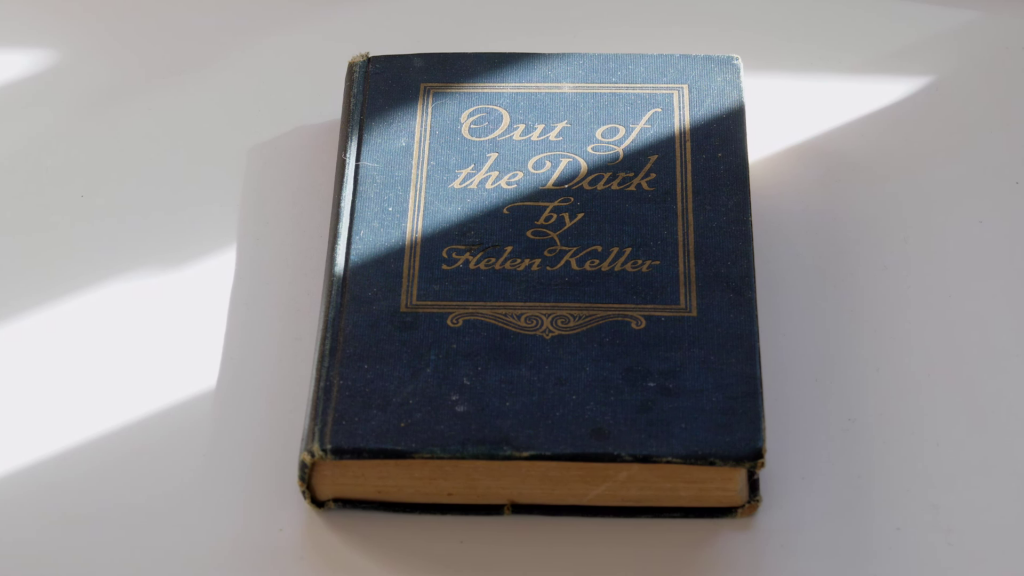

As for my reading, the list is quite extensive as I read a great deal over the last few years including, among others, both of Helen’s autobiographies, her book of essays Out of the Dark, her book-length poem, The Song of the Stone Wall, a collection of her selected letters, and four different collections of her speeches and texts — Philip Foner’s Helen Keller: Her Socialist Years, the Rebel Lives series volume on Helen Keller edited by John Davis, Lois Einhorn’s Helen Keller, Public Speaker, and Helen Keller: Selected Writings edited by Kim Nielsen. Nielsen’s other book, The Radical Lives of Helen Keller (2007) I would rank as one of the best of the biographies, although I also read Dorothy Herrmann’s book and Joseph P. Lash’s massive and detailed if overly opinionated Helen and Teacher. This is apart from extensive reading of period newspaper articles in the collections of the Perkins School for the Blind and the American Foundation for the Blind.

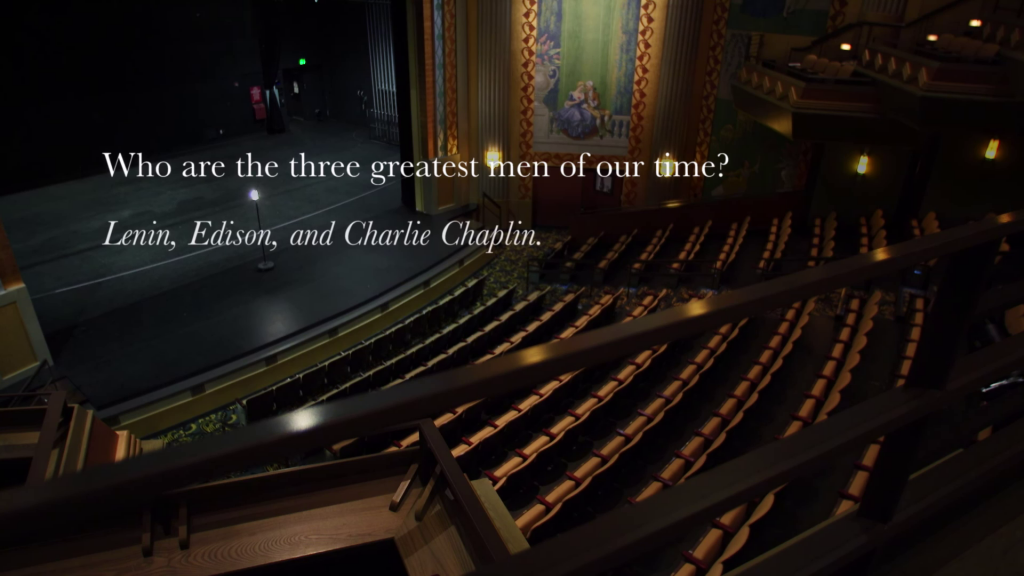

Cineaste: Your shots of nature, including creatures who neither see nor hear (at least as we understand those terms), as well as certain locations (like a theater’s empty stage and seats and a former Keller home), all call to mind the way that you privilege grave sites in Profit Motive and the Whispering Wind (2007) as well as Vapor Trail (Clark) (2010) and Wake(Subic) (2015), although these images and sounds function quite differently here. But even more striking to me is how much of your film gives us texts by Keller to read — a radical step that also makes us aware of how sophisticated and accomplished Keller was as a writer, in a literary sense. Combined with her extraordinary capacity for self-education, this clearly marks her as a genius, however unaccustomed we are to granting any women that status.

How deeply do you consider her writing related to Anne Sullivan’s collaboration — or is it even possible to determine this? Is her writing style similar to Keller’s, or different? This seems relevant to Helen’s frank confession in The Story of My Life to having inadvertently committed plagiarism as a child when she wrote a story called “The Frost King” similar to a story that had once been read to her, although she had no conscious recollection of it. “It is certain that I cannot always distinguish my own thoughts from those I read,” she writes, “because what I read becomes the very substance and texture of my mind.” Seeing her own identity as part of a collective identity, a socialist identity, follows naturally from that sentence. What do you think? Am I being too fanciful?

Gianvito: The answer, I think, is slightly complicated. The particular Teacher–Student relationship between Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan was certainly unique, and one that’s been characterized as an almost “unanalyzable kinship.” They lived an extremely intimate life together spanning nearly fifty years throughout which time Helen always referred to Anne simply as “Teacher.” And while Anne Sullivan would acknowledge that she was closely involved in assisting, editing, and proofreading Helen’s manuscripts, she declared it a “deep injustice” whenever it was suggested that she was in any way the true author. I find this fairly well corroborated by others who also assisted in the editing of Helen’s books, such as John A. Macy and Nella Braddy Henney.

As for the whole “The Frost King” affair, it’s clear that Helen was extremely mortified by it and her unconscious absorption of aspects of Margaret Canby’s story, though interestingly, Canby actually felt that Helen’s version was superior. It’s also been surmised that the trauma, at eleven years of age, of publicly being accused of plagiarism, led to Helen never again writing works of fiction.

While Helen was reliant on Anne for so many things including, as pertains to the writing, keeping her typewriter in working order, looking up words, and bringing a certain cohesion to Helen’s fragmentary style of composition, Helen was known to be throughout her life a feverish writer and avid reader. And, as far as their politics, they certainly were not aligned, as Anne was not a socialist and not even a supporter of women’s suffrage.

Cineaste: Here’s a question from our mutual friend, Nicole Brenez: Who is the Helen Keller of today? Or, alternately, who are the Helen Kellers of today, assuming that such a thing is conceivable?

Gianvito: I am not sure I’m in a position to say. For one thing, it’s important to stress that Helen Keller’s most tangible and prolonged achievements were in the advocacy works she performed on behalf of the blind and the deaf, none of which are the focus of this particular film. To be sure, Helen’s drive and determination from an early age, her dogged optimism and literary talent, contributed to her celebrity and ability to inspire and lead. And in this one might perhaps make comparisons to someone like Greta Thunberg who, at such a young age, already has galvanized so many around the issue of our global climate crisis, and who has described her own diagnosis of Asperger syndrome not as a disability but as her “superpower.” But it’s also important to point out that, no matter what intrinsic gifts Helen possessed, her rise to success benefited as well from a measure of class privilege, by early support from the likes of Alexander Graham Bell and Mark Twain, by Anne Sullivan’s own ambitions for Helen, and by a voracious media. As to her legacy, in the intervening years so many disability rights advocates in so many countries have made significant strides in passing improved legal protections and promoting increased awareness of disability issues, though I imagine most of us do not know their names. In terms of the promotion of socialist ideals today, my thoughts naturally turn to some of our current political representatives such as Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Kshama Sawant, and Bernie Sanders, among many others who are contributing to a culture that refuses to see the word “socialist” as a pejorative.

Cineaste: Here’s another question from another mutual friend and fan of Her Socialist Smile, Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa, who says she loves your images of books in the film. She’d like to ask you why, about two-thirds of the way through the film, the letters in an on-screen text turn red and start to move, accompanied by a revolutionary song.

Gianvito: An aesthetic decision. I’d been compiling a compendium of stirring quotations from Helen for years that hadn’t otherwise found a home in the film, many from her most outwardly militant period, including her remark embracing the Red Flag, which triggered the thought about “Bandiera Rossa.” Leftist anthems have been a motif in my films for some time. I try to incorporate them with an ear toward nontraditional renditions as a way of reinvigorating these melodies and propelling the themes of the work. In Profit Motive, it was Ani DiFranco and Utah Phillips’s instrumental recording of “The Internationale.” In Vapor Trail (Clark) and Wake (Subic), I used more melancholic versions of the Italian partisan ballad “Bella Ciao,” one by Giovanna Marini and Francesco De Gregori, and one recorded for me in Tagalog by Lav Diaz. Thinking this time about the Italian communist song “Bandiera Rossa,” by chance I happened upon a remarkable rendition done in the 1980s by the famed Slovenian punk rock group Pankrti. When you get to know the real Helen Keller, she had a bit of the punk ethos about her. I was so pleased when I reached the group’s founder Gregor Tomc and he relayed that they’d be honored to have their music in such a film.

Cineaste: It strikes me that one thing all your films have in common is that they comprise history lessons of one sort or another, and these lessons are always related to facts that have been buried and/or forgotten. This is even true of the more recent history explored in The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein, the resistance to the first Gulf War, and I recall that the epigraph from Cesare Pavese opening that film’s first part is, “Everywhere there is a pool of blood that we step into without knowing it,” which would apply equally well to your nine-hour diptych, For Example, The Philippines.

I have to admit that this ignorance and/or memory loss applies even to people like me who revere your work, because a few months ago, you sent me a copy of your 1990 short, significantly called What Nobody Saw, and even though I saw it right after it arrived, I no longer remember what it’s about, and I’ve even managed to misplace that DVD-R. It’s an embarrassing yet telling lapse on my part. Could you remind me and also tell our readers something about this film? After all, an alternative title for Her Socialist Smile might be What Nobody Heard or What Nobody Knew, and it seems that an intrinsic part of capitalist logic is “out of sight, out of mind.”

Gianvito: What Nobody Saw was a fifteen-minute short I made with my friend, poet Fanny Howe. It was our second collaboration and made very hand to mouth in Super 8. Fanny’s synopsis is as follows: “Three figures —man, woman, child — roam the grounds of a State Mental Hospital, a kind of hell on earth, looking for each other or for a supreme witness to their loneliness. A visual poem with voices off.” The “voices off” being those of Fanny and poets Robert Creeley and Peter Gizzi, although there exists an alternative cut of the film that I allowed Fanny to assemble in 2015 that uses Creeley’s reading only. It’s a very open text and hard to characterize though I would say it touches on the theme of our obligations to others than ourselves. By the way, I noticed that Fanny Howe posted What Nobody Saw at some point on her Vimeo site —- https://vimeo.com/16146779 — so you needn’t keep searching for your lost DVD. I also posted Vapor Trail (Clark) on YouTube myself, given how hard it is for folks in the Philippines to access it otherwise, though reliable Internet is also a major issue in the affected communities. I have not yet posted Wake (Subic) — only the trailer.

What you say, Jonathan, about my films being explorations of forgotten or suppressed history is no doubt the case. But as Howard Zinn repeatedly emphasized, the study of history is never a neutral act. It interests me primarily, as it did Howard, to the degree to which it’s useful to one’s present circumstances, its targeted capacity to both provoke and help energize the long struggle for a more just and egalitarian society.

How “willful ignorance” factors into all of this and this propensity we all have to “turn a blind eye” not only to the past and its most shameful pages, but also to so much of what unfolds around us daily, is actually at the center of a project I’ve been trying to develop for a number of years now. I see it as the organic outgrowth of much of my work these past decades. The present title is The Ash Heap of History and it’s inspired in part by the writing of the late South African sociologist Stanley Cohen, in particular his book States of Denial. How one makes a film on such a topic I still don’t know, but it seems every time I have an idea for a project it appears to me utterly impossible. And then I just get to work.